Summary

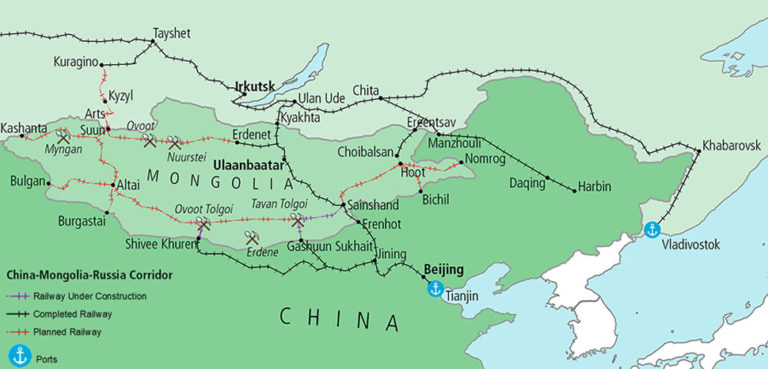

The New Eurasian Land Bridge is one of the six major corridors envisioned by China’s One Belt One Road Initiative. It’s also referred to as a branch of the China-Central Asia-Western Asia Corridor, or as part of the New Silk Road Economic Belt. The project aims to streamline cross-border trade by modernizing rail infrastructure linking China’s restive western region with Europe via the Russian trans-Siberian railway, branching northwest from Urumqi, traversing Astana in Kazakhstan, and then linking up with the Russian rail network at Yekaterinburg. The route will bypass the southern leg of the trans-Siberian railway in northeast China and offer a more direct route through Xinjiang. It will also diversify China’s shipping away from seaborne routes that bottleneck at the Strait of Malacca.

Overview

Building up a Eurasian rail corridor. The New Eurasian Land Bridge is relatively straightforward compared to some of the other economic corridors of the One Belt One Road Initiative: it traverses only three countries on the way to Europe, it focuses on freight transportation, and the existing infrastructure is already largely in place, albeit in desperate need of modernization in some cases. The focus of investment has thus been on improving track and accompanying facilities along the route, which in turn allows for faster transport times and makes the route more competitive with seaborne and airborne freight options. Europe and China’s rail infrastructure is already at a relatively high standard; it’s the Kazakhstan and Russian segments that are most in need of new investment in order to improve train speeds. For its part, Kazakhstan has initiated a $2.7 billion upgrade program for some 724 km of track along the New Silk Road route. Russia has also been upgrading the trans-Siberian railroad through the 2000s, and is even thought to be mulling a western extension to the Japanese island of Hokkaido.