Perhaps one of the most quoted predictions regarding the increasing role of water conflicts in global affairs belongs to former vice-president of the World Bank Ismail Serageldin, who in 1995 famously claimed, “Many of the wars of this century were about oil, but wars of the next century will be about water.” While oil has long dominated the geopolitical thinking of world powers, the new millennium promises to elevate the importance of water resources, potentially triggering conflicts in water-starved regions of the globe. The most obvious and fundamental problem with water management is that 97% of water on earth is impractical for drinking or agricultural purposes since it’s enclosed in the world’s oceans. As U.S. Army War College Professor Dr. Butts in his renowned article The Strategic Importance of Water wrote, “Only three percent of the water on the earth is fresh and, of this, more than two is locked away in the polar ice caps, glaciers, or deep groundwater aquifers, and is therefore unavailable to satisfy the needs of man.” The previous century did in fact witness several serious stand-offs between neighboring states that were at odds over sharing adjacent water resources. Consider the conflict between India and Pakistan over the Indus River basin that was exacerbated after the British partition. Had the World Bank not intervened, a violent clash between New Delhi and then the capital Karachi would have been inevitable. The ongoing negotiations brokered by the World Bank resulted in the Indus Waters Treaty of 1960. Among myriad examples of water conflicts is the famous case of the Argentina-Brazil border dispute over the Alto-Parana basin that took decades to resolve. The agreement was finalized in Itaipu-Corpus Multilateral Treaty of 1979.

The cases of water conflicts are many and the 21st century won’t be immune to major complications that water scarcity may cause. The world has already witnessed the calamitous events unfolding in Syria which produced one of the greatest humanitarian crises of our times. The internal unrest in Syria that led to a civil-war is often attributed to Assad’s oppressive regime. However, what doesn’t really get much attention is the severe drought that forced over 1.5 million people into urban areas putting immense pressure on social services. The mismanagement of water supplies by the Syrian government further exacerbated the water scarcity. Not hard to guess that those affected took to the streets further contributing to the social unrest that transformed the anti-government protests into a multilayered conflict making Syria a battleground for regional powers.

The Iranian regime has been criticized for deliberately over-consuming water reserves to benefit the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Almost exactly the same pattern is apparent in Iran, where recent protests signaled the growing frustration of the populace over some of the pressing issues that remain untackled. Among the most urgent problems such as the skyrocketing prices, costly military expenditures at the expense of social services, and high unemployment, one danger is particularly striking: declining water resources, which is poised to become a major national security threat. There are several factors that explain the causes of the Islamic Republic’s drying water reserves. London’s Imperial College’s Kaveh Madani identifies three main factors that have sent Iran’s water supplies into a downward spiral. Iran’s population, Madani claims, has grown exponentially draining the water reserves. The incompetent agricultural sector too has had detrimental effects. And, of course, the mismanagement of water resources that have brought Iran to the verge of a water crisis.

Tehran’s unwise exploitation of water resources is not a new phenomenon. The chain of bad decisions has lasted for many years leading to alarming depletion of water bodies throughout the country. Two major water bodies have particularly suffered. Lake Urmia, one of the largest salt lakes in the world, is on the brink of disappearing. The lake has suffered due to incredibly high agricultural consumption, giving rise to serious concerns that if the pattern continues Urmia will soon cease to exist. And, of course, the Zayandehrood river, which flows through central Iran and was the lifeline of the city of Isfahan (the city owes its existence to the river), is drying too. The approximately two million people who live around the basin have suffered immense hardships as declining agriculture has affected their livelihoods.

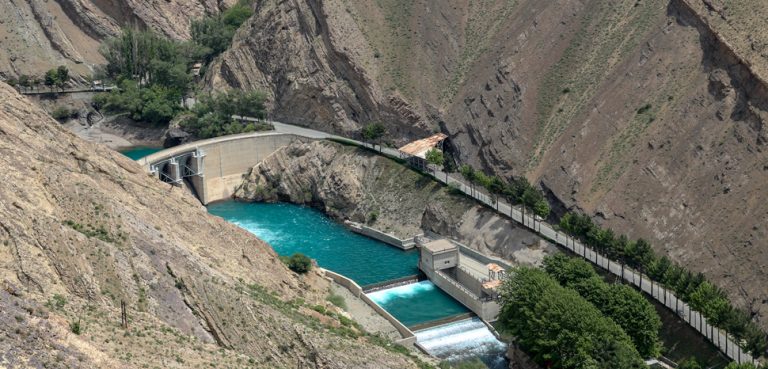

But what one cannot ignore is the role of the government that aggravated the water crisis. The Iranian regime has been criticized for deliberately over-consuming water reserves to benefit the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) that was originally created to protect Ayatollah Khomeini from an internal coup. After the Revolution, the IRGC was granted a large stake in Iranian economy which included an ownership of construction companies that freely engaged in various engineering ventures. To illustrate this point in a piece written for Washington Post, Seth M. Siegel claims, “Recklessly, these companies began damming major rivers, changing the historical water flows of Iran. This was done to give water preferences to powerful landowners and favored ethnic communities while also transferring billions from the public treasury to IRGC leaders’ accounts. In all, since the 1979 revolution, more than 600 dam projects have been completed, contrasted with 13 dams built in Iran prior to the shah’s fall.”

To alleviate the massive water shortages and halt the coming hydro crisis, Tehran has reached out its neighbors to gain access to the latter’s reserves. For instance, Iran began actively engaging with Armenia to import water from Lake Sevan since 2012. The purpose was to bring enough water to save Lake Urmia from vanishing. The Armenian side decided not to move forward with the proposal due to political reasons. Speaking of Iran’s attempts to gain access to region’s water resources one wouldn’t be wrong to assume that Tehran will try to engage with Artsakh Republic (also known as Nagorno-Karabakh) as well. The Republic’s Shahumian and Kashatagh regions are known for their ample water resources thus serving as water security guarantors for both Armenia and Artsakh. Moving forward, Tehran will take concrete steps to gain access to these water resources.

In addition to plummeting water resources at home, Iran will face another water related problem as Turkey begins exploiting the Ilisu Dam over the Tigris River. Iranian officials, including President Rouhani, have been quick to condemn Ankara’s construction efforts citing the environmental degradation that it will cause. The Dam is expected to reduce the flow of Tigris into Iraq by 56% which in turn will affect Khuzestan’s Kharkeh River that technically brings life to the Hour-al-Azim Wetland near the Iraq-Iran border.

If Iran’s water crisis continues, the fate of the country could be akin to Syria’s inner migration crisis leading to a massive unrest across the country. It is premature to conclude whether the days of the regime are numbered or not. But the recent protests are symptoms of a growing bubble that can burst at any moment. After all, even local Iranian officials have acknowledged the coming migration crisis due to reckless water use. In 2015, Vice-President of Iran Issa Kalantari (also Head of Department of Environment) warned that if Iran doesn’t dramatically change its water policies close to 50 million people would be forced to leave the republic. Given the current environmental indicators, Kalantari’s predictions are quite alarming.