Coverage of Vladimir Putin’s impending return to the Presidency of Russia on March 4th has so far focused almost exclusively on the menace posed to Russia’s teetering democracy. Conspicuously, little analysis has been offered regarding the impact Putin’s eminent reprisal of the Kremlin’s top job is having on Russia’s foreign policy – particularly when it comes to how political events are playing out in Syria and the Middle East.

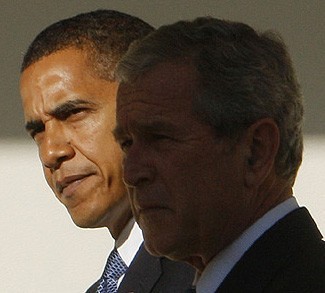

Throughout his presidency, informed observers have maintained that President Dmitry Medvedev has been the puppet to Putin’s puppeteer. In several areas of foreign policy however, Medvedev wielded a substantial degree of independence until recently. Medvedev’s ascension to the presidency coincided with Obama’s arrival in Washington and the new leaders enjoyed decidedly more amicable relations than Putin experienced with Obama’s predecessor, George H.W. Bush. Putin’s successor has displayed a markedly more benign outlook towards the liberal values espoused by Washington and to the White House itself, further encouraging a rapprochement between Moscow and Washington.

The ideological differences between Putin and his successor emerged most noticeably in the wake of NATO’s bombing campaign against the forces of former Libyan dictator Muammar Kaddafi. Putin, incensed by France’s delivery of weapons to Libyan rebels, fumed that UN and NATO actions resembled “a medieval call for a crusade.” In contrast, Medvedev cautiously supported UN actions against Libya, pointing out that Kaddafi’s regime was committing terrible crimes against its own people. Even more, Medvedev bristled at Putin’s use of the word ‘crusade,’ arguing that such language threatened to “lead to a clash of civilizations.”

Russia, under Medvedev’s guidance, thus allowed the March 17, 2011 UN Security Council resolution authorizing military intervention in Libya to pass, deciding not to use its oft-used veto in the voting process. But while Medvedev may have looked surprisingly favourably on UN intervention in Libya, Putin – and Beijing for that matter – determined to counter what he sees as Western attempts to destroy anti-Western governments.

Since the September 2012 announcement that President Medvedev would step aside in order to allow Putin to reassume the Russian presidency, Russia has returned to its traditional, realist foreign policy.

Last week’s European-Arab UN draft resolution outlining Arab League plans to transfer power from Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to his deputy was consequently dead in the water from the outset. Moscow and China double-vetoed the proposal, ensuring that no international collective action can be taken against the Assad regime.

The Syrian imbroglio underscores two essential, arguably structural, sources of conflict between Moscow and the White House. At the regional level, wrangling over Syria is a microcosm of the struggle between the US and its allies on the one hand, and China and Russia on the other to be the kingpin in the Middle East. The Iran-Syria-Hezbollah axis and its ties to the Kremlin is a crucial piece in the chess match between the White House and the Kremlin to control regional resources; and the Kremlin can ill afford to have its strongest allies in the region weakened or even disappear.

While the US and its allies undoubtedly fear a post-Assad Syria either controlled by Islamists or in complete chaos a la Iraq, Washington nevertheless relishes the opportunity to weaken Moscow’s staunchest ally in the Middle East.

Antagonism over Syria also stems from a fundamental clash of ideologies concerning the right of the international community to infringe on state sovereignty. Whereas Washington and its Western allies endorse the concept of the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ (at least when it does not impinge on national interests), Moscow has a long history as a champion of state sovereignty harking back to the Soviet era. ‘Responsibility to Protect’ for Putin the realist means little more than thinly veiled subterfuge for regime change – more often than not directed at Russia’s allies.

Moscow’s antagonism toward international intervention in Syria is part of carefully laid plans to expunge the advances made by the UN Security Council in the past year – during which time the UN twice intervened in Libya and in the Ivory Coast in the name of the ‘Responsibility to Protect.’ According to George Lopez, a professor at Notre Dame University, the “Russian veto this week [is] the latest manifestation of their rejection of their pro-active, norm-enforcing Security Council that has emerged in the past decade.”

Now that Putin has emerged for Round Two of his Kremlin tenure (if he ever in fact disappeared), the Russian Bear is once again showing its claws – and it bodes poorly for progressive forces caught in the gigantic power play between the Kremlin and the White House.

Victor Mac Diarmid is a contributor to Geopoliticalmonitor.com