This week, GPM is pleased to interview Dr. W.E. (Ted) Hewitt, one of Canada’s leading authorities on Brazil.

Introduction

Dr. Hewitt is a Professor of Sociology at the University of Western Ontario in London, Canada and Visiting Public Policy Scholar at the Brazil Institute at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C.

In this 45 minute interview, Dr. Hewitt offers critical insight into Brazil’s role in the 21st century and its ascendency to global power. Dr. Hewitt addresses a wide spectrum of issues ranging from the history and shape of Brazilian-Canadian relations to what Canada can learn from Brazil’s technological advancement and expertise.

This interview is a must-read for anyone interested in South America’s emerging giant.

Can you begin by offering us some perspective on the history of Brazilian/Canadian relations and how they’ve evolved over the last century?

The short answer is very up and down. I would say that the reality is somewhat different from the popular perception which has been propagated in many quarters that Canada and Brazil are countries that have a lot in common, that we had been working together for the better part of a century — that we established relations early on at the beginning of the 20th century by selling cod fish to Brazil which is still very popular at Christmas — by establishing companies such as Brascan which built the hydro-electric and telephone systems for growing cities like Rio and Sao Paulo, through to our collaboration in Italy during the Second World War, to our joint peace-keeping efforts in the ‘50s and ‘60s in the Suez, right up to our joint peace keeping in Haiti.

The reality is that we have had really little to do with each other as countries. It is only now that we are getting serious about working together. I believe that this is because, for the first time, Canada truly understands how to approach Brazil from the perspective of developing a solid bi-lateral relationship. I think a lot of our approaches and efforts during the ‘90s and into the first decade of this century were based on a somewhat misguided notion that Brazil was an “emerging” power, developing country, that could somehow benefit from all that we had to offer as Canada through our education system or through our highly-evolved bureaucracy, our democratic tradition.

In fact, this hasn’t interested Brazil very much. Now the government’s tone has shifted to focus on how Canada collaborates with Brazil, specifically in areas such as science and technology, student and researcher mobility, to create value together and specifically in the form of inventions, knowledge, and technologies that can be developed, marketed within our countries, and to third parties in ways that Canada and Brazil can in fact go after world markets. Only now has the relationship started to take off in my view.

Would you say then that prior the turn of this century, Canada had somewhat of a paternalistic tone in its relations with Brazil?

Very much so.

What did that tone stem from? Was it specific to Brazil or did that pertain to all of Latin America?

Paternalistic, yes, because that’s the way developed countries so-called, in the 80s, 90s, and beyond, tended to deal with developing countries. You know, we had it all, we had a solid economy, we had the benefit of solid health care systems and educational systems and these countries were in the process of acquiring them. So of course, we knew better and we were working hard to work with these countries to “help” them.

Almost, as if we were taking a colonial perspective?

Yes. Although of course, you have to understand too from a Canadian perspective or a US or European perspective, it was about selling products and services to these expanding markets in areas where we had a technological, or a service, or another advantage.

Definitely paternalistic, for sure.

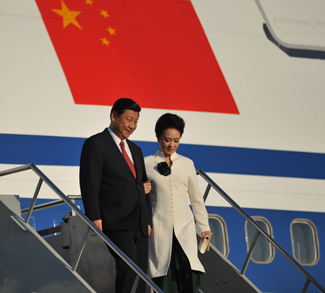

Ok. Could we make a comparison in that regard to the way that Canadian/Asian, specifically Canadian/Chinese relations have evolved?

I think Canada realized more quickly, or earlier on, that China and India were on to something in terms of technological development than they realized Brazil was. And I don’t think Canada has a very good position on Russia at all, or a very good understanding of what Russia has to contribute.

As a BRIC country, I think there’s some appeal. But, in Canada, it was very well-known years back, for example, how good the Indian Institutes of Technology were and how these students were really top quality and how we should be recruiting them to Canadian universities and how that sort of signified a level of sophistication that was emerging in the Indian economy.

In China it was obvious because they were producing so much by volume of our imports. You know how they moved into producing technology goods, high quality, and at a level of sophistication that obviously demonstrated that Canada needs to be cooperating with China.

I would say at the same time that, India and China are still seen very much as “natural” suppliers of students to Canada based on the belief that these countries need to educate and train their younger generation in ways that they are currently not able. And that is true. But, again, it kind of pays a bit to the more paternalistic view.

Considering the similarities between Canada and Brazil in terms of technology, I find Canada’s paternalistic approach odd. I mean, Brazil in the 1970s with Aerospace and Embraer and a number of other industries seemed to be relatively advanced comparatively.

Yes.

Why then, was Canada unable to recognize the comparable advancements in Brazil?

Well that’s a good question. I think initially Canada – and I’m speaking in regard to government – viewed Brazil as an emerging competitor in the ‘90s and the early part of the first decade of the 21st century. In fact, I still hear this very often. Brazil had developed this technological expertise, it was creating a lot of stress for Canada particularly as a result of the competition with Bombardier. That’s what drove the whole approach to the WTO in the ‘90s. A former Canadian Ambassador to Brazil once told me in no uncertain terms, in fact, that Brazil was a competitor and that it had to be “wrestled to the ground” in these areas so it wouldn’t get an advantage over Canada. So that was the thinking. And that has now sort of abated in part because there are so many areas now that are well-recognized in Brazil as offering opportunity to Canada in terms of collaboration, as opposed to simply competition.

I mean, I just mentioned a few. Ethanol production and flex gasoline/ethanol based engines for automobiles. Off shore oil exploitation through the work that’s been done by Petrobras. Mining through the work that’s been done by Vale – the high-tech, now increasingly environmentally sustainable types of extraction methods. Agriculture – massive-scale agriculture in Brazil in so many areas that’s producing huge opportunities for export. And then, bio-tech.

So, I think Canada’s starting to realize that Brazil is, if not outright taking ascendancy — and it is in some areas (in Aerospace and ethanol production) — is quickly moving toward the top of the pile in a number of key areas. My argument was, years ago, and I think it’s finally starting to sink in and starting to stick, that if we’re not working with Brazil now, they’re going to be more than competitors in 5 or 10 years, they’re going to be threatening a whole host of industries in this country because of the expertise they have and their lower cost of labour.

I guess now would be an appropriate time to touch on potash. What is the state of Canadian potash relations with Brazil currently? I was reading that by 2020, Brazil will be the world’s largest consumer of potash so is that a specific area where there can be increased collaboration between Canada and Brazil, or is Brazil primarily focusing on extracting it internally?

Right now, my understanding from the Brazil-Canada Chamber of Commerce is that the largest single commodity that Canada exports to Brazil by volume is potash and Saskatchewan is the largest single exporter to Brazil of all Canadian provinces. The demand for potash is tremendous in Brazil and probably will remain so as the agricultural sector grows. On the other side of the coin it’s interesting because in dollar value, we are importing from Brazil increased amounts in goods in the form of finished products — steel, automobile parts, aircraft – and by volume we’re exporting raw materials to Brazil. This is somewhat contrary to what you’d think would be happening in that kind of a relationship with a developing/emerging economy.

That leads into my next question as to how natural resources can affect the manufacturing industry. I think in February the decline in the manufacturing sector was approximately 2-3% from the previous month. What steps is the Brazilian government taking to prevent ‘Dutch Disease’ and what can Ontario and Canada as a whole learn from the Brazilian experience?

Ok, to go back a bit. Brazil’s industrial expansion occurred in two phases. One was through policy and government intervention in the 1930s through the formation of huge government steel companies, mining and even automobile production. Then, there was a kind of import substitution during the 50s, especially in automobiles starting with Volkswagen. Then with the military after ’65 there was wholesale investment and development of huge multinationals with government backing – like Vale, Embraer, Petrobras. And even now, even though they are nominally private-sector and traded on stock markets, government owns huge chunks of these and has a stake in managing them. So, state intervention and a high tariff regime attracted all sorts of supply companies through the ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s. Today, Brazil produces something like 80-95% of all of the manufacturing goods it consumes and is a major exporter as well.

But now, as you say, industry production rates are sagging. (I just saw an article today in the Brazilian press – there was a huge demonstration in Sao Paulo today with 10,000 workers protesting against the shrinking of the industrial sector and calling on the government to formulate a new industrial policy). So, it is serious. There is a lot of parody about this. In Brasilia, the Chamber of Deputies in the Senate, there was a kind of funny demonstration where two Brazilians were dressed as Chinese there to officially thank Brazil, on behalf of the Chinese government, for exporting so many jobs. This is clearly a big thing.

Now, in terms of policy, one of the things that Brazil has done is to encourage or sometimes force (through regulation), companies including their own big investor companies like Vale, Petrobras and others, to invest billions of dollars in R & D to try and get ahead of the technology curve to preserve these jobs in Brazil. I think that’s a key strategy. Brazil is aiming to spend much more of a percentage of its GDP over the next few years in R & D. The kind of money, for example, that Brazilian agencies have to throw around versus their counterparts in Canada particularly is pretty amazing.

In terms of the lessons for Canada, I see two things. I saw Stephen Harper here in Washington on Monday at the Wilson Centre, articulating a policy for Canada that is basically a natural resource policy as opposed to an industrial one. It’s a bit of a concern frankly. I mean we’re going back 120 years but that’s where the money is and that’s where the government thinks it needs to drive the successes. There is no industrial policy in Canada that I’m aware of. There’s an innovation agenda but it has no direction and no foci. It talks about the need to get ideas out of universities and government labs into industry, but it doesn’t say what industries or even what we’re good at really or where we should really be focusing. And that’s a political issue in Canada. So I think until we really start to talk seriously about where we want to dominate globally as a country, we’re going to continue to languish or rely on the price of oil and potash to keep this economy afloat.

Now Brazil made those decisions and they invested heavily in sectors like agriculture through EMBRAPA, their national agency for promoting technological innovation through agriculture. Through Embraer, through off-shore oil discovery technologies where they lead the world. Petrobras spends 1.2 billion (USD) every year on research. 1.2 billion. It’s as much as NSERC and SSHRC spend each year on research funding in Canada for all researchers.

So that’s what their strategy has been. I don’t think you’re going to see high-tariffs come back and I don’t think you’re going to see them come back in Canada. I think those countries that are smarter, that invest in people because talent is very mobile, ideas are mobile, countries need to grab at, and secure, the smartest and most talented people with the best ideas and put them to work in the service of innovation and then develop those innovations at home. The Brazilians have done this much better than Canada has over the years and will continue to do so. Now of course, they’re possible victims, as you say, to this Dutch Disease, so they need another big thing. But they’re still holding on nicely in those areas which are highly technological like aircraft. Last time I looked, Embraer had more orders on the books than Bombardier.

And would you attribute that to federal legislation?

In Brazil, yes. Totally. Assistance for exports for investments that Embraer has been encouraged and/or mandated to make in R & D.

So what would be your policy advice and suggestions to improve research and development and technologies in Canada if you had Stephen Harper in a room?

I think, and this may not be popular and I did write a piece for Research Money in December where I was fairly critical of the Jenkins panel. I think they had an opportunity to absolutely recommend a total overhaul of our support for industrial R & D and how that links to universities and federal science and they chose simply to tinker. To be fair, that is exactly what they were asked to do by government. They were not to go out and reinvent the whole system and had to work within the current confines of funding. But even in that constraint they could have at least begun to rethink how S & T is pursued in Canada and how it’s encouraged.

For example, and this would be a big piece of advice, even goal setting on the percentage of GDP that Canada should invest in R & D. Like South Korea has said 5%. Brazil, I think is saying 5% of GDP to R & D. Even that small step is enough to say that is where we want to go and then start measuring that. It’s like everything, as soon as you start measuring it stuff starts to happen.

Then the next step would be to say what are we good at, and in terms of industrial policy, where does Canada absolutely have to lead at as a national priority. Well, they never said aerospace but for all intents and purposes we might as all just admit it, call it a day. Aerospace, maybe it’s mining, maybe it’s auto or materials, but figure out what the array is, start to focus on training, invest in universities to attract the best and brightest from all over the world.

You know, we did this in Ontario. I worked on a provincial panel through the Council of Ontario Universities that developed the blueprint Ontario’s Trillium Awards which were these PhD scholarships that Ontario funded last year that the Premier announced in China. And then what happened? There was a huge backlash. What are we doing funding foreign students when our own students can’t get spots in universities? It’s nonsense. They are PhD spots designed to bring high-end talent to Ontario and to Canada. Folks we badly need.

My advice would be to set targets for R & D spending. Is it going to be 5% or what because right now it’s only at about 1.8%. Set something. Number two, pick the areas that are critical for Canada and be bold about it. Don’t be afraid of it, embrace it. And make sure there are industrial areas named where we must lead. And then, thirdly, mobilize people and ideas in order to do that. So that means develop a better innovation system, put those incentives in place to get those technologies out of universities, to get universities to attract best and brightest foreign students, to get them aligned in areas that are useful for industries to build these competencies. And I’ve said it more than once, the question is politically that this just doesn’t sell for the reasons that we just talked about. Government’s are afraid to pick areas and then things don’t work well in those areas and it’s their fault and they’ve just potentially wasted millions.

Seeing as we’re on the topic of foreign students, I suppose that this discussion leads somewhat naturally into my next question on Brazilian foreign relations. What are Brazil’s major trading partners and what I really want to get at is, are these relationships based on a historical foundation? Where do you see Brazilian foreign relations going in the 21st century?

Ok, that’s another good question. I think you’ll find Brazil’s traditional trading partners are in Europe and they’re in the US. Increasingly though, in terms of where it’s going, and to some extent in the last 20 years, it’s been more “in the neighbourhood”. The “neighbourhood” as they call it in Brazil being the countries of South America.

Is Mercosur working?

For Brazil, yes. But there’s a lot of complaining in some of the member countries because Brazil is using this as a way to enhance its industrial production and to export to these countries. The fact is that these countries have benefited tremendously as well from Brazilian technology, from free importation into the Brazilian market. So they really don’t have a lot to complain about and they know it. You get a lot of popular sentiment as you did in Canada with NAFTA, saying that the Brazilians are going to own everything and take it over. But the fact is now, that smaller countries like Uruguay now have access to the Brazilian market, 200 million people. Of course, Brazil has access to their markets and they are producing more sophisticated goods technologically and their selling those goods in those countries like cars and so forth.

So, Brazil has done very well and they want to keep building that relationship in the “neighbourhood”.

The second thing is the BRICS. There was a meeting in New Delhi this week which has clearly demonstrated how important this constellation is becoming; and also, for Brazil specifically as it works to assert its desire to be a global player.

And do you think their aim of becoming a permanent member on the Security Council will happen or is that simply a symbolic gesture?

No, Brazil has always had very strong ties to the US that it uses quite effectively, and obviously US support for this will be key. For its part, the US sees Brazil as one of its closest allies in South America and really the lead broker for its interests in the region. But, yeah I think Brazil sees itself as aspiring to that and the BRIC alliance is one way to get it. Also, these BRIC countries are huge markets for Brazil. China is a huge market for Brazilian iron-ore and you name it.

So, the “neighbourhood”, the BRICS countries and then Africa is a key priority for Brazil. They are approaching Africa in a very interesting way as well through very creative use of “cultural” bilateralism, particularly in the Portuguese speaking countries.

Particularly in former Portuguese colonies like Angola and Mozambique?

Yes, the Portuguese speaking countries first. There are Brazilian cultural products that are sold there, films, television, education — they bring students to Brazil. This can open the door to Brazilian companies bidding on projects like infrastructure which are increasingly the norm in Africa. Large development companies like Odebrecht. And they go into Mozambique getting contracts because they are already sensitive to the culture through knowledge of the language and they’re particularly smart about developing projects that meet local country needs i.e. less technology intensive, more labour intensive. They bring schools, they help develop communities, so they do it in a culturally sensitive way that makes friend. And this is a hugely popular approach.

Would you draw any parallels with the way the Brazilians and the Chinese are operating in Africa?

I wouldn’t. The Chinese send their citizens to Africa and other areas to work and Brazil doesn’t do that so much. Brazil uses local labour, in high quantity and that is actually very popular.

Popular for good reason…

Of course. The Chinese tend to come in and do everything themselves and they send people to do it. So an investment of 20 million from China wouldn’t remotely look like an investment of 20 million from Brazil. In fact, China pours billions into Africa. Brazil makes investments but in cultural areas and that paves the way for business for companies that do very well in Africa but in a culturally sensitive way.

Yet, I recently read that in Nigeria for instance, 75% of the population approve of Chinese involvement in their country. But I suppose that the Chinese, in this regard, are taking a much more colonial or 19th century style imperialist approach to Africa.

They are. And they approve because there is tons of cash coming in. Nigeria’s fairly wealthy also because of their oil. But if you’re in Mozambique or Angola and you speak the language, there is a cultural tie, students are in school in Brazil, Brazilian teachers are working there; in the end, you want to do business with people you know and are familiar with. The opportunity is salient for these Brazilian companies and they are taking advantage of it.

On the topic of education, what is the state of the education system in Brazil and who are the students they are attracting? Do they have a strong international base?

The answer to the last question is not so much. Most international students in Brazil are from “the neighbourhood”. They are from Colombia, Venezuela, Spanish speaking countries. They would like to have more. And there are more students coming from Africa. There are also a fair number of Haitian refugees that are making their way to Brazil as well.

They want more. They have their Science Without Frontiers Program to send more Brazilian students out to other countries. That program will also see students coming to Brazil. They would like to see a lot more. That is a real opportunity for Canada as we develop closer ties in science and technology. That not only has to involve research, it has to involve moving people both ways not just one way.

So we have to create a dialogue.

For sure. I think the educational system, to answer your question, the post secondary system looks a bit like Canada in the sense that there are a similar number of students enrolled even though Brazil is 6 times bigger than Canada, so it’s modest. Also, the postsecondary sector is about 80% private, 20% of spots are in the public institutions, some federal some municipal. These are free and you have to work hard to get in. They are very high quality. The anomaly is that they are high quality, very difficult to get in. It’s much easier to get into a private institution if you have the money and of course, you don’t need the marks either.

On the primary and secondary level, there have been some modest gains. The numbers actually enrolled in primary school have gone up hugely in the last couple decades but they still have a long way to go in terms of public education. In that sector, 90% of students are in the public sector. 10% are in private schools. They have a long way to go before you could say their primary and secondary systems look anything like Canada’s in terms of quality.

Ok, well I’d like to do a 180 if possible and get into defense. It seems that historically Brazil has been a relatively peaceful country with a small military and a focus on cooperation rather than being an antagonist power. How would you look at Brazil’s role in the 21st century from a security and defense perspective?

I think Brazil’s role has been characterized as using ‘soft’ power. And you’re right, there’s no military threat there. They have a respectable military and they have one aircraft carrier, fighter jets and a pretty good navy, good standing army and they are engaged throughout the country, particularly in frontier regions. But they’re not threatening anybody.

It’s interesting that I’ve never heard of any talks about Brazil pursuing nuclear weapons though.

Well there used to be, back in the ‘70s there was worry that the military was using reactor technology to possibly build an atomic bomb. Obviously, this was false. Brazil is heavily engaged in the defense industry though. They make lots of armament, including fighter craft, which are sold globally. I don’t see that as changing at all and I don’t see anything in their stance that could remotely characterized as hawkish.

So when you characterize Brazil as a ‘soft’ power…

Well, I think it’s a ‘soft’ power approach.

Would you say then that Brazil, as a superpower, will more heavily rely on more of its cultural exports?

Yes. I think that’s the plan in Africa. Don’t go in with guns a-blazing. With Iran, Palestine, Israel it’s about talk, negotiation, collaboration and cultural exchange and that’s exactly what they’re doing in Africa.

How do you then see Brazilian foreign policy in terms of conflict resolution? Will they maintain peace initiatives?

Yes I think so. I think they will play a significant role in mediating disputes. They tried that in Iran although I don’t know how successfully. Certainly, the US would see them in that role in South America in mitigating some of the potential damage or issues created by Chavez in Venezuela. And I think they like that role, that’s where they seem themselves. As a global mediator, honest broker etc.

What does that stem from? Are there historical reasons behind Brazil’s ‘soft’ approach?

Well I think historically that’s the role they’ve played. They were combatants in the Second World War in Italy mostly because of the links with that country in terms of immigration. But you know they served in peacekeeping with the first UN units in the late 1950s and with the Canadians in Suez. I think they certainly see themselves as making peace not war and have historically. The approach has never been really aggressive. I think they would see that it is much to their advantage to maintain this sort of non-aligned, less aggressive tact in order to win friends and make potential trade partners globally.

Still, I find it surprising that historically Brazil has never made aggressive moves within South America.

Well there was a war in the 19th century with Paraguay. Paraguay lost a major portion of its territory. That was over 140 years ago and the last major conflict in South America.

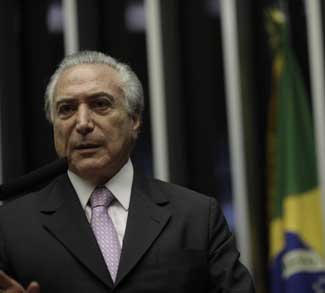

Could you briefly touch on the corruption issues Brazil currently faces?

Brazil has a very poor score on the Corruption Index. If Canada is in the top 10% Brazil is firmly in the middle to lower end. There’s a strong sense of entitlement that’s led to corrupt practice at levels right up to the Federal Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. I think to some degree, it was tolerated as part of the cost of doing politics in Brazil under Lula. What we’re seeing with Dilma Rousseff is a complete turnaround and she just doesn’t tolerate this even remotely. I can’t remember what the number is, but close to seven or eight last count, of her ministers have been sacked because they have been caught out on shady dealings typically involving some payoff or links to companies that have benefited from some government policy or procurement.

It’s endemic, right down to the municipal level. This isn’t about paying off traffic cops. This is about major corruption on the part of politicians who receive federal or state funding and basically feather their own nests or improve the lot of their friends.

Will this ultimately hinder development in the country?

Well sure because lots of cash gets diverted from productive ends. If they’re shuffling it off-shore to Switzerland or other places then the money is lost from the economy. It also sets a bad precedent in a country where the gap between rich and poor is still fairly broad. I think the Human Development Index is .55 so it’s getting better. But, the inequality index is still fairly high. However, particularly because people are getting better educated and have access to the Internet, the people just aren’t putting up with corruption like this anymore. The people are complaining very loudly. It used to be “who cares, they’re all corrupt, to hell with it”, now it’s “no, this can’t be allowed to happen, somebody has to do something”.

So yes, it will be a hindrance until this can be sorted but I think it is happening. It is inevitable.

So ultimately you don’t see corruption as a major stumbling block on Brazil’s global ascendancy?

Well, I’m encouraged that they are dealing with it. A lot of people still say it’s endemic and it will be difficult and that the corrupt will never be punished. It’s a fact, in Brazil certainly your ability to hire a lawyer can help you a lot. Unless you’re at a certain level like these 17 executives at Chevron who can’t leave the country. If it’s found that they were negligent or tried to cover up. At a certain level, they don’t fool around.

You’re outlook is therefore positive?

Yes because the President has given a signal that corruption will no longer be tolerated.

There are currently rumors that Lula is considering a return to politics. What is the likelihood of that happening?

Well it depends. He has been very sick with cancer and is now recovering well. He is certainly involved in the politics of Sao Paulo mayoral race, and others. I have no doubt he will be involved in the next presidential race at some level, but, I would be stunned to see Lula go after Dilma as a candidate for the presidency. If she does well she will be immensely popular. So that means another four years. I don’t see it happening.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.