Summary

The standoff playing out between China and the Philippines over the disputed Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea may one day be looked back on as the harbinger of a renewed American military presence in the Philippines.

Analysis

The current standoff began on April 10th when Chinese ships intervened to prevent a Philippine Navy vessel from detaining Chinese fishermen who were caught fishing in Philippine territorial waters. What followed were several days of posturing on both sides, as Chinese patrol boats were sent in and then recalled, and the Philippine Navy boat was pulled out and replaced with a coast guard vessel. As of April 16th, both sides are keeping ships in the disputed area.

Of the many points of conflict that currently exist throughout the South China Sea, this one is particularly important because of the geopolitical fallout it might entail. The Scarborough Shoal is well within the Philippines’ 200 mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), making China’s current military excursion to protect its fisherman stand as a rather stark breach of sovereignty, or at least sovereignty as it’s defined under the UN Law of the Sea. For the government of the Philippines, this breach couldn’t come at a worse time. A month hasn’t even passed since the last ASEAN summit came to a close in Cambodia without an agreement on how to resolve overlapping claims in the South China Sea. Essentially, Manila has been left with no diplomatic recourse in dealing with an increasingly assertive Chinese government; one that now seems willing to deploy its military assets in Philippine territorial waters.

With diplomacy off the table and a Chinese government that isn’t shy to put its $114 billion advantage in military spending to work for it, Manila is in need of allies that can help it redress this military imbalance. And of course, there’s no better ally for this than the United States.

Ever since the Philippines Senate voted to shut down Clark Air Force Base and the Subic Naval Base in 1991, the United States has been quietly deepening its indirect military links with the government of the Philippines. In 1999, the Philippines-US Visiting Forces Agreement came into effect, allowing for the deployment of US troops under a very loose pretense of ‘training missions.’ And this was followed by another agreement in 2002 that allowed for the storage and pre-positioning of US military equipment in Philippines territory.

This legislative build-up towards a renewed permanent deployment will intensify now that popular opinion within the Philippines is sure to swing back in favor of leveraging the United States military against an increasingly threatening PLA Navy. In fact, the idea of US military bases in the Philippines wasn’t even terribly unpopular back in 1991, and most of the anti-base sentiment grew out of urban elites who believed, somewhat ironically given present circumstances, that the bases infringed on national sovereignty.

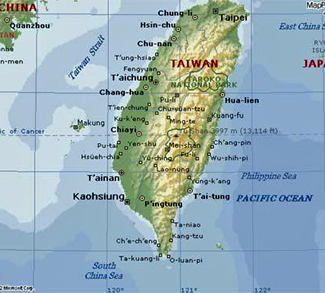

On the American side, new permanent bases in the Philippines would be a masterstroke for Obama’s Asia-Pacific pivot policy. The United States has been expanded its Pacific footprint into Australia and it is now upgrading airstrips on the Cocos Islands between Australia and Sri Lanka. A new base in the Philippines would provide several benefits: it would help to frustrate the PLA Navy’s attempts to expand its defense perimeter, it would allow for a quicker and multi-pronged military response in the event of a conflict over Taiwan, and it would establish the US military as a counterbalance against Chinese assertiveness when dealing with other South China Sea claimants, including Washington’s other new friend- Vietnam.

With so much to lose from a possible re-establishment of permanent US military bases in the Philippines, it seems a little strange for Beijing to want to back Manila into a corner like this. It’s possible this hyper-aggressive stance on the South China Sea might be a little domestic political posturing in the lead-up to the rollover in Chinese leadership later this year. The next generation of Chinese leaders could very well wise up to the risks of new American bases and go hard on the diplomatic track; it’s just a question of whether or not it will already be too late.