The successful blend of Islam, democracy, a dynamic economy, and significant historical weight make Turkey uniquely qualified to assume a powerful role in the region.

Under the leadership of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), Turkey has positioned itself as a major regional mediator for the Middle East and greater Muslim world.

Turkey has been a democratic country since 1922, when Mustafa Kemal Atatürk founded the Republic of Turkey from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire. Atatürk’s vision of modernization took the form of various Western-minded reforms, the most important of which was a stringent emphasis on secularism, which was meant to subvert the Islamic influence that had pervaded Ottoman society. To this end, Atatürk adopted a legal system based on Swiss Civil Code, a unified, secular education system, and replaced the Arabic script used for Turkish with a Latin-based one. With a population that is approximately 99% Muslim, Turkey is unique among its neighbours in having achieved a secular, democratic state.

This synthesis of Islam and democracy in Turkey is being watched closely by surging democratic movements in the Muslim countries of the Middle East and North Africa. Tunisia’s newly-elected Islamist Ennahda party frequently refers to Turkey as an example for Arab states to follow, and Libya’s National Transitional Council has also been vocal in its praise of the Turkish model.

Turkey’s policy towards its neighbours has shifted radically since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The centerpiece of this shift is the doctrine of so-called “strategic depth.” Coined by Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmed Davutoğlu, this policy calls for Turkey to play the role of regional peacemaker through the use of its extensive soft power. Davutoğlu argues that Turkey occupies unique geographic and historical positions, qualifying it to deal with regional issues. Wedged between the Middle East, the Balkans and the Caucasus, and with a Turkic-speaking, Sunni-Muslim population, it would seem that Davutoğlu’s words hold true.

While Turkey has been a staunch U.S. ally in the past, the rise of an independent Turkish foreign policy has caused the two countries to diverge on several issues. Two such instances include the refusal to allow American troops to invade Iraq from Turkish territory and Ankara’s sharp criticism of Israel’s actions in Gaza.

In spite of these divergences, a more ambitious and independent Turkish foreign policy does not signal a meteoric break in relations with the United States. While Ankara is no longer as eager to please Washington as it was during the Cold War, Turkey has a number of similar strategic objectives to the U.S, including the maintenance of a stable westward flow of energy supplies and coordinated anti-terror strategies. This relationship is also obviously quite valuable to the Americans, as Turkey’s Sunni majority and far-reaching legitimacy among Muslim countries leave it well placed to resolve disputes that the U.S. cannot.

Despite extensive economic ties with Iran and several failed attempts to diffuse the Iranian nuclear standoff, Iran has emerged as Turkey’s major geopolitical rival in the Middle East. In particular, Ankara’s decision to host early-warning radar stations for the U.S.’ ballistic missile shield has angered Tehran, and Iranian officials have even gone so far as to threaten attacks on targets within Turkey.

The Islamic Republic holds significant influence over Shia groups across the region, including Hezbollah in Lebanon, the al-Assad regime in Syria, and factions in Iraq. As Turkey tries to extend its influence among Sunni groups in the Levant, it consistently comes up against long-entrenched Iranian proxies.

The most obvious arena of this kind of Turkish-Iranian competition is in Syria. Despite early calls for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to enact reforms, Ankara has fallen in line with the international community’s support for an overwhelmingly Sunni opposition movement. Turkey also hosts some 23,000 Syrian refugees as well as training camps for the Free Syrian Army. Iran is meanwhile a long-time supporter of the al-Assad regime, and has every interest in preserving its regional ally. Turkey sees the Syrian crisis as an opportunity to cut through Iran’s sphere of Shia influence, and looks to eventually bring Syria into its Sunni fold.

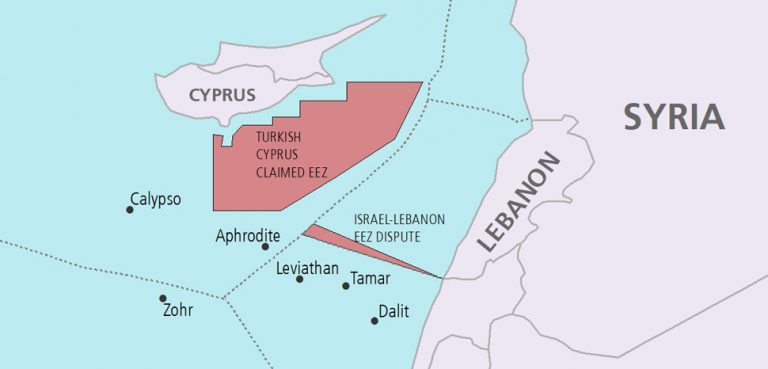

Traditionally-close relations between Turkey and Israel have frayed significantly in recent years. Turkey has deep ties to the Jewish state, having been the closest relationship of any Muslim state to Israel for decades. However, increasing Turkish ties to the Muslim world has led Ankara to re-evaluate these relations.

The on-going Israeli blockade of the Gaza Strip has emerged as a particular source of tension. The May 2010 Gaza flotilla raid marked a turning point in Turkish-Israeli relations. The incident was met with widespread hostility in Turkey, and Ankara ended up downgrading diplomatic ties and suspending military cooperation in September 2011.

Tensions with Israel have also stirred up historical animosities with Greece. Israeli-Greek ties are increasing, evidenced by the decision to include Greece in joint U.S.-Israeli military exercises in the Mediterranean in March 2012.

Turkey’s relationship with the European Union is a complicated and a strained one. The country first applied for formal EU membership (then the European Community) in 1987. Under the AKP, Turkey has made enormous strides in reforming its judiciary, economy and civil-military relations to conform to EU standards. Despite this, the EU has repeatedly denied Turkey membership. Erdoğan has consequently steered Turkey away from the EU and to closer to its Islamic neighbours.

Turkey is fast becoming an essential energy supplier to the EU despite this political slight. As European states seek to diversify energy imports away from Russia, Turkey has stepped in to fill this void. In October 2011, Turkey concluded a deal to buy gas from Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz-2 oil field for transport to Europe. This effectively bypasses Russian and Iranian territory. Turkey is also looking to court Turkmenistan, which some believe to have the world’s third-largest oil reserves. A trans-Caspian pipeline running from Turkmenistan through Turkey into Europe would greatly increase Turkey’s strategic importance as a gas transit state for the EU.

Increased U.S.-Turkish cooperation in recent years, namely the planned construction of NATO missile bases in Turkey, have exacerbated tensions with Russia. Moscow sees the placement of these sites as part of a larger U.S. attempt to curb Russian power in the region. Yet neither Russia nor Turkey has much of an appetite for conflict. Russia is nervous about Turkish influence in the Caucasus and Turkey is acutely aware of its energy dependence on Russia.

Turkish relations with Central Asian states are another area of importance. The former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan all share a Turkic cultural heritage with Turkey. These historical and linguistic bonds have led Turkey to reach out to its Central Asian cousins, culminating in the creation of the Turkic Council in 2009. As a part of their never-ending struggle to escape Russian influence, the Turkic Central Asian states are expected to increase ties with Turkey over the coming decades.

As the international system shifts from a world of unrivalled American dominance to one of competing centres of power, Turkey is well-positioned to thrive. Its geographic, demographic, and historical uniqueness allow the country considerable flexibility in its relations with other states. And its status as a successful Muslim-majority democracy, combined with a surging economy and an-increasingly confident leadership may just see the county grow into the role of regional powerbroker in the coming years.