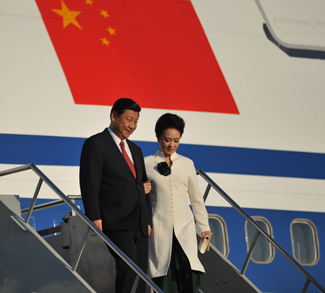

The National People’s Congress put its final rubber stamp on a series of appointments this week, filling out the remaining unknowns of the government that will rule China for the next ten years. The appointments contained no surprises: Xi Jinping as president, Li Keqiang as premier, Li Yuanchao as vice president, Wang Yi as foreign minister, and Liu Yandong as vice premier (returning a lone woman to the highest levels of the government). Zhou Xiaochuan was also kept on as the governor of the People’s Bank of China, which suggests that the new regime is serious about pushing through a range of economic reforms, such as exchange rate liberalization and the lifting of various capital controls.

The challenges facing this new administration are as obvious as they are pressing. It must keep the Chinese economy growing at a steady clip while simultaneously beating back growing discontent over official corruption, environmental issues, and income inequality. And now that all of the positions have been filled out, the question is no longer who will be resolving these problems, but rather how they will be resolved.

Right out of the gates, the new regime has come out swinging against corruption by acquiescing to a Wen Jiabao-initiated reorganization of one of country’s most corrupt government institutions: the Ministry of Railways. This is the ministry that was presided over by the now-disgraced Liu Zhijun, who was arrested in February 2011 after being accused of accepting over $160 million in bribes. It has a debt level that exceeds the size of the Danish economy and employs over two million people, making it a true bureaucratic colossus of the planned economy era. The new reform will split the Ministry of Railways into two parts: a Ministry of Transportation that’s in charge of the day-to-day administration of China’s railways, and a private company that will handle its commercial operations.

An orderly transition from the corrupt and bloated Ministry of Railways to an efficient and transparent China Railways will be a daunting task, but as far as the Xi Jinping administration is concerned, the PR benefits are already being reaped. The Ministry of Railways has come to represent many of the problems that are plaguing the Chinese political system, so to take aim at the ministry is to strike a highly symbolic blow against corruption and inefficiency; even if the same transgressions will inevitably continue in the future, albeit this time at a state-owned corporation.

Li Keqiang referred to the potential for far more vigorous steps against corruption during a press conference, when he responded to a question on that indirectly invoked Wen Jiabao’s family assets. Mr Li was quoted as saying public officials should give up the prospect of making money and accept the supervision of the public and the media. This admission could be a precursor to rumored reforms that would require Chinese leaders to publically declare their assets and income.

Mr Li also dropped a few hints that he was ready to continue playing ‘good cop’ to the president’s ‘bad cop,’ in substantive policy if not grandfatherly tone, carrying on the tradition of his predecessor, Wen Jiabao. In his speech, Li Keqiang vowed to cut government perks and allocate money to social welfare programs. He also pledged a ban on new government building construction and curbs on official banquets and travel allowances. Many of these promises are calculated attempts at establishing a broad populist appeal, and now it remains to be seen whether they can be followed through on.

Another interesting trend can be gleaned from Xi Jinping’s inaugural address, a speech that was broadcast on just about every channel in China. Mr Xi made repeated reference to a “Chinese Dream,” in which the Chinese nation would come together to regain its historical status as the most civilized country on earth. His choice of stressing the more ancient parts of Chinese history is telling, as it shifts official rhetoric away from the more vitriolic aspects of modern Chinese history and the “century of humiliation.” This might signify an understanding on the part of the Chinese government that peaceful Sino-Japanese coexistence is not being served by populist nationalism (which exploded across the country in anti-Japan protests lasts year), and that the CCP is ready to adopt the more benign mantle of ancient Chinese history as an ongoing justification for one party rule.