A preliminary deal has been reached between the P5+1 parties and Iran, establishing a series of restrictions on the country’s nuclear program in exchange for a partial reduction of the sanctions that have decimated the Iranian economy. The agreement represents a breakthrough in US-Iranian diplomacy since the 1979 Revolution, and the new normal it envisions could have a profound impact on not just the geopolitical reality of the Middle East, but the global economy as well.

The deal was helped along by secret talks between US and Iranian representatives – another exceptional event given the disregard and mistrust that generally passes for bilateral exchange between the two countries.

The Geneva deal is only a temporary agreement which is set to expire in six months. Talks will continue over this period in the hope of hammering out a permanent deal.

The agreement lifts sanctions targeting Iran’s ability to trade in gold, petrochemicals, and car and plane parts. Some estimates put the amount of relief Iran can expect from these concessions at $7 billion (the majority of which comes from $4.2 billion in frozen assets being released). Opponents of the deal offer an even higher number, arguing that Iran can expect to benefit to the tune of $20 billion, even though some of the harshest sanctions targeting oil sales and the banking sector remain in place.

In return for the easing of sanctions, Iran has agreed to: stop enriching uranium above 5%; dilute its existing stockpile of 20%-enriched uranium; stop stockpiling low-enriched uranium; freeze its enrichment capacity and the installation of any new centrifuges; keep the heavy-water reactor at Arak inoperable, neither adding fuel to it nor turning it on; not build any new facilities; and accept a series of stringent inspections from the International Energy Agency.

The net result of these concessions, particularly the dilution of its stockpile of 20%-enriched uranium, would be to shift the Iranian nuclear program further back from the threshold where it could quickly produce a nuclear weapon. The kind of inspections laid out in the agreement (daily, intrusive, and far-reaching) would make it very difficult for Iran to operate a parallel enrichment program in secret without being discovered early enough for the international community to react.

Winners and Losers

Supporters of the deal are holding it up as a historic breakthrough. They point to the fact that it puts verifiable limits on Iran’s ability to produce a nuclear weapon. The more optimistic among them even see it as a potential harbinger of the normalization of US-Iranian bilateral relations.

Detractors see things differently. For them, the deal represents a caving in on the part of the United States and its Western allies, which ultimately decided to drop the precondition of a total and permanent halt of enrichment activities, as well as the dismantling of certain facilities such as the reactor at Arak. The survival of Iran’s right to enrich uranium in the deal is their main point of contention.

The right to enrich uranium, which is carefully delineated as being ‘mutually defined’ in the text of the Geneva agreement, will figure prominently in the following six months of negotiations. It is the point of convergence where Iranian nationalism meets international law, and the argument will revolve around whether uranium enrichment is included in the “inalienable rights” of peaceful nuclear development set out in Article IV of the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

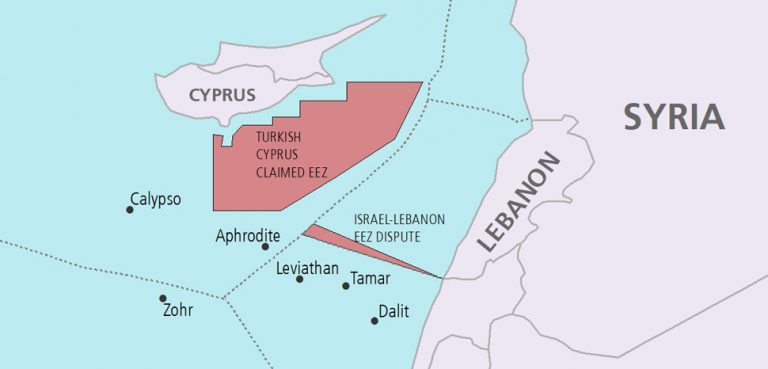

One of the most vocal detractors so far is Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who has declared that the world has been made a more dangerous place by the deal. Israel had been one of the parties pushing for a complete halt to enrichment activities as a prerequisite for any sanction relief. Thus, the deal comes as a blow, as it represents the fracturing of the international coalition pressuring Iran. It follows that Israel would face a more pronounced international backlash if it were to unilaterally move against Iran’s nuclear infrastructure in the post-Geneva international climate.

Saudi Arabia is another government that isn’t taking many positives from the deal. If Geneva represents the first step in the international rehabilitation of Iran, then the Saudi government stands to lose as its regional rival steps out of the shadow of international isolation and begins to throw its weight around more freely in the Middle East. In this sense, the Geneva deal might be less about binding Iran’s nuclear potential and more about the United States disengaging from a volatile region of the world, one that is less geopolitically crucial in the wake of the North American energy boom.

Domestic Backlash

While it’s apparent that President Obama and President Rouhani want the Geneva process to succeed, albeit each with their own nuanced view as to what that success should entail, both leaders are presiding over domestic political opposition that could scuttle the deal in the next six months. In the United States, members of Congress are already lining up to voice their disappointment with the agreement, and a bipartisan group of 15 senators has announced their intention to pass additional sanctions against Iran in the coming weeks. Any additional sanctions would be seized upon by hardliners in Iran as evidence that the US is not negotiating in good faith, and a breakdown in the negotiating process would likely follow.

Oil Exports

Although the Geneva deal represents a potential turning point in US-Iranian relations, it is far from a game-changer in terms of Iranian oil exports; at least for now. Among the sanctions that remain in place under the temporary deal are those restricting foreign investment in the oil sector, as well as an export cap of one million barrels per day (bpd). Consequently, Iranian oil exports can only hope to increase by around 285,000 bpd, up from the 715,000 bpd recorded in October, over the short term.

The real surge in exports would come if the Geneva deal was extended into a comprehensive agreement, though even then it might take some time for Iran to reach its previous capacity. The added supply on global markets would reduce oil prices by up to $13 a barrel according to one estimate by Citigroup, giving an added impetus to economic recovery worldwide.