According to the best laid plans of several world governments, January 22nd will see the UN-brokered “Geneva II” talks attempt the near impossible task of negotiating an end to the brutal conflict in Syria, which has killed over 130,000 people so far and displaced millions. Or, alternatively, the talks might be over before they even begin, boycotted by a major party or doomed to fail by immovable and hostile negotiating positions. Either way, Geneva II’s prospects for success are presently wallowing in the gray area between ‘slim’ and ‘none.’

One might say that the key problem hounding the conference is a pervasive disconnect between idealistic and dogmatic thinking and the reality of the situation on the ground. The first example of this can be found in the very origin of the conference. Geneva II was not born out of war wariness or a belief on the part of the war’s combatants that a military victory could not be won. It was imposed from the outside, by Western, Russian, and UN diplomats seeking an end to the terrible suffering being heaped on the Syrian people. This is not to say that the goal of a negotiated and peaceful end to the conflict is not worthwhile, but rather that since the push for talks is coming from without, the internal actors involved have not yet had their negotiating positions tempered by the hopelessness of fighting on – they’re not ready to sacrifice their own immediate goals in the interests of peace.

For proof look no further than how difficult it was to get the necessary parties to come to Geneva II. Everything short of kidnapping was used to ensure attendance, particularly with regards to the Syrian National Coalition, and every subsequent offhand comment (al-Assad’s intransigence) or surprise development (Iran’s invitation) risks someone pulling out.

Another disconnect is evident in the stated goals of the Geneva II peace process, as encapsulated in the 2012 Geneva Communique (again, drafted by outside parties). These goals envision the establishment of a pluralistic multi-party democracy after a transitional period, and by doing so they adopt the authoritarianism-democracy framework prevalent at the outbreak of hostilities in Syria – back when the al-Assad regime was just one more domino lined up to fall in the Arab Spring’s democratic wave. But the reality of the situation on the ground in Syria demands a different interpretation, say nothing of later developments in the other democratic ‘success stories’ of the Arab Spring: Libya, Tunisia, and Egypt.

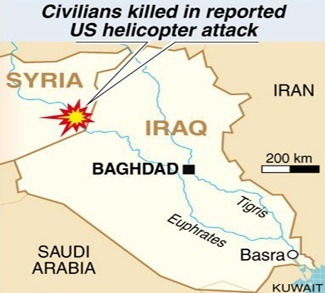

The Syrian conflict is now about state survival and regional stability rather than political emancipation or democracy building. In the eyes of Russia, and increasingly in the eyes of various Western powers, the al-Assad regime is a necessary evil in avoiding state collapse, anarchy, and a power vacuum that would surely be filled by terrorist groups, impacting wider regional stability. We are already seeing this to a certain degree in the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant’s (ISIL) straddling of the Iraq-Syria border, simultaneously fighting in the Syrian civil war while helping to take over several cities in Iraq’s Anbar province.

US policy planners have no doubt realized the strategic risks of the present course as well, and it is now looking like the Obama administration would rather the devil it knows in a stable yet tyrannical al-Assad regime than the one it doesn’t in whatever rises up from the ruins of state collapse. So regardless of how ‘surprised’ US diplomats seemed in response to the initial announcement – don’t be fooled. It’s almost certain that Ban Ki-Moon got the nod before he went ahead and invited Iran to attend.

Viewed in this light, the Geneva II talks are about reconciling the ideal with the real; or securing a tenable end to the fighting that leaves enough central state authority intact as not to be torn apart by forces of entropy, whether sectarian, religious, or paramilitary.

In other words the talks are about saving face, and herein lies a slim possibility for success. If the Syrian National Coalition comes to terms with the fact its negotiating position has been seriously compromised by the Western world’s willingness to accept al-Assad in exchange for stability and an end to the killing, then it’s conceivable it would accept a deal offering cosmetic power sharing in a transitional government tasked with “fighting terrorism” and, at some vague and indeterminate point in the future, initiating a nebulous process of constitutional reform. Because make no mistake: that’s the kind of deal that will be on the table.

The Arab Spring gave Western governments a glimpse of what democracy and institution building in the MENA region might look like, and so far the results haven’t been overly positive. Thus, when the doors open on the Geneva II talks, expect the al-Assad and Iranian delegations to be holding all the cards; the only question that remains is whether the opposition delegations accept it or not.