Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, has signed a controversial anti-gay law that establishes sentences ranging from 20 years to life imprisonment for, quite simply, being gay. The legislation had actually been nicknamed the “Kill the Gays” bill, because it went so far as to establish a death sentence for the so-called offenders.

The Ugandan Parliament passed the law on 20 December 2013. This odd and medieval law was strongly supported by evangelicals in Uganda and in particular the evangelist pastor Solomon Male, who has been supported by the US-based American Evangelical International House of Prayer among other ‘Christian’ groups, seemingly eager to take their ‘struggle’ from America – a lost case with its abortion and gay rights – to Africa. In other words, the anti-gay law is not just an odd local Ugandan phenomenon; it is part of an international effort to push similar legislation to receptive governments throughout Africa. The Catholic Church, more influenced by the messages of the New Testament than the more austere Bible, has issued a timid reaction, despite Pope Francis’ earlier statements signaling that the Vatican may be ready to adopt a more conciliatory stance towards homosexuality.

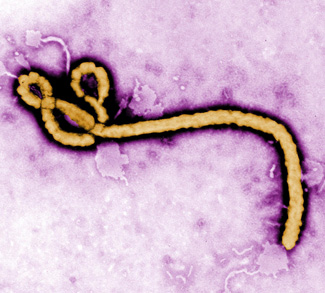

In effect, one would expect such legislation and attitudes from the Taliban or some clerics in Saudi Arabia rather than in Museveni’s Uganda, one of the closest Western allies in Africa. Yet, Ugandan evangelists, more extreme than the Mullah Omars of this world, encouraged by Americans have managed to convince the majority of Uganda that the HIV epidemic is exclusively the result of homosexual practices. Governments in Europe and the United States have condemned Museveni’s decision without announcing formal sanctions, and threats to cut off aid have not yet been enforced. Some 30% of the two billion dollars of foreign aid received by Uganda is used to sustain government spending in health, education, and defense.

The US State Dept. has estimated aid to Uganda to be in the order of some $400 million a year in addition to military support; and Secretary of State John Kerry said that could be cut in the wake of the new anti-gay law. In the European Union (EU), Denmark is one of the main donors to the Ugandan government; the Danish Parliament has suggested diverting official state-to-state aid to independent NGOs. Other Scandinavian countries have suggested similar approaches. Sweden’s Finance Minister Anders Borg, who visited the country on Tuesday, said the law “presents an economic risk for Uganda.”

The United States has condemned the anti-gay law but in this case there has been no threat of sanctions. Indeed, one of the reasons that Museveni could sign such a hateful bill into law so boldly is because he has little to fear from Western retaliation. Indeed, Uganda has been gradually shifting its attention to China, which is by far, Uganda’s main investment partner. The West, and the United States in particular, has been largely relegated to the role of aid donor, but the actual Ugandan economy is growing thanks to Chinese backing. Chinese investment in Uganda continues to gain volume. China has obtained the rights to develop oilfields and the Chinese oil company CNOOC will look after development of the Kingfisher deposit. China will also invest in the phosphate sector; Guangzhou Energy Dongsong has invested nearly $560 million that will be used to set up a mining operation to produce fertilizer and sulfuric acid.

If that’s not enough, Uganda may also be able to rely on Russia for support, given that its own (though far less insidious by comparison) homosexuality laws would certainly not allow it to make any grandiose humanitarian gestures in this sense. By adopting the law, Uganda, which in the last ten years has made great strides towards development, has collapsed into the Grand Inquisition of the Middle Ages. And in doing so it shrugged off all threats of foreign aid cuts and international criticism, simply noting that it could do without Western aid: “The West can keep their ‘aid’ to Uganda over homos, we shall still develop without it,” did declare government spokesman Ofwono Opondo, ironically using the very 21st century Twitter.

Though it may be difficult to gauge, the anti-gay bill allegedly passed with strong public support and Museveni will run again for re-election in 2016. He has been in power for the past 28 years. If there is one major reason why donor nations should not cut off aid altogether it is that there are still political entities in Uganda that are already challenging the bill. Uganda, after all, is supposed to be a democracy. Opposition leader Kizza Besigye said that Museveni has used homosexuality as an excuse to “divert attention from domestic problems”. Two of these problems are the various emerging corruption scandals and Uganda’s military involvement in the South Sudanese civil conflict. Nevertheless, many multilateral agencies are feeling pressure to act. Last week, the World Bank suspended $90 million in healthcare funding in response to Museveni’s signing of the bill.

It would be easy for others to follow suit in order to put pressure on the Ugandan government; however, at the risk of being banal, two wrongs do not make a right. Withdrawing healthcare funding flies in the face of the humanitarian standards that donor nations purport to uphold; it would punish the wrong people. The ruling class that signed the anti-gay legislation, more likely than not, obtains health care abroad; it does not need the funding. The vulnerable people who might benefit from the World Bank aid, however, will now, out of no fault of their own, lose that coverage. Moreover, if donor agencies and governments were to abandon Uganda, it would only end up strengthening the anti-gay lobby that pushed for the bill in the first place.

Western protests – unless they are more strategically applied – will end up sounding to the public like the “Western cultural imperialism” that Museveni said homosexual rights represent. It would be far more useful for Ugandans and for the ultimate success of democratic and liberal values for donors to remain and to continue aid efforts. This would help in keeping the Ugandan people engaged with Western values and improve the situation from the base of society, rather than the top down.

Museveni is perhaps even hoping to elicit Western scorn in order to distract the population as he prepares for the 2016 election. Indeed, it should be noted that Western donors have already cut off aid to Uganda in the past two years to the tune of $300 million because of government corruption. As much the Ugandan authorities deserve to be condemned for their anti-gay legislation, donor agencies and NGOs should continue to operate and provide assistance because the people of Uganda should not suffer because of the draconian decisions of their government. Perhaps military aid should be subject to review, but where cooperation and development programs concern education, poverty reduction, economic opportunity creation, and healthcare, no cuts or threats of cuts should be applied. One need merely look at the record of international sanctions. Sanctions have failed to dissuade so-called ‘rogue’ states from pursuing nuclear programs (Iran, North Korea) or from overturning unfair legislations, releasing political prisoners, or ending a conflict in Myanmar or Syria. The biggest example of sanctions failure and isolation might be Cuba, where more than 50 years after sanctions were first applied, the Castro brothers and their brand of communism are still in charge.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.