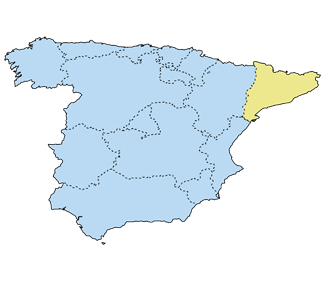

Since September 2012 the world’s mass media has been buzzing, on and off, with a new contender to become an independent nation: Catalonia. This doesn’t mean it hasn’t been independent before, or that the independence movement has appeared out of the blue. But the largest demonstration in Catalonia’s history, organized by a grassroots non-partisan organization that had emerged on the stage just a few months earlier (the Catalan National Assembly), and calling for independence, surprised and captured the imagination of many.

And that was nothing compared to the huge international impact of the human chain spanning 250 miles, from one end to the other of Catalonia, exactly a year later (see a picture of it here).

On each occasion well over a million – some sources speak of nearly two million, which is over a quarter of Catalonia’s population! – people took part, demanding independence in a totally peaceful, civic fashion. Not a single firework broke the magic. Catalans formed and filmed smaller chains in over a hundred cities right across the world, with a single aim: to decide democratically, that is, at the ballot box, the political future of Catalonia.

Moreover, the Parliament formed after the snap election in November 2012 on the self-determination ticket has a comfortable overall majority, which has been particularly visible on several occasions, and most specially on December 12 2013, when the date (November 9 2014) and the question to be put in the referendum were agreed and announced.

Has Spain taken all of this sitting down? Well, lots of things can be done while seated. It has not called out the troops (which does not mean threats have not been made) to prevent the vote. But it has refused point blank to contemplate even a non-binding poll on the subject. It has engaged in a number of efforts to divide the Catalans, well outlined over a year ago by Ramir de Porrata-Doria in his article “Divide et Impera: l’estratègia d’Espanya contra el sobiranisme,” though its only success up to now has been to force the Catalan Socialists to back down on their election pledges in favour of a referendum, or at least to abstain in Parliament on the issue.

One of de Porrata-Doria’s predictions involved the Catalan language, a centuries-old thorn in the flesh of every Spaniard who yearns for a monolingual country. Catalonia’s democratic language-in-education policy, only contested by the Spanish conservatives and radicals, meagrely represented (compared to other parts of Spain) in the Chamber, resembles that of Flanders in Belgium, or the Ticino canton in Switzerland. In a nutshell, teaching is in the local language, and all pupils are expected to have a good proficiency of the other official language of the country when they leave school. For years now, this policy, though upheld in the highest courts, has gradually been gnawed away at the edges. Right now, there is a big outcry, for a court has ruled that if in a classroom, 29 parents want a Catalan-medium curriculum, and a single parent wants a bilingual one, then that parent’s wish is to prevail over the will of the 29 others. Such an undemocratic stance, which now has the backing of a Spanish organic law (called an “education quality” act, despite being criticized by parents and teachers alike) is also a slap in the face for tens of thousands of Valencians whose formal choice of a Catalan-medium schooling for their children is thwarted every year by a serious shortfall in provisions.

And it has continued an unabated programme of recentralizing reforms which will substantially reduce the levels of home rule, could force the closure of many public agencies in Catalonia, and even threaten the existence of the vast but fragile Ebro Delta.

A battle is being fought for world public opinion. A former Socialist minister, Catalan-born Carme Chacón, has bluntly stated that “Catalonia should remain part of Spain.” Others have been spoon-fed with tales about “Catalan Independence and a Tumultuous 2014 for Spain”, or flatly told that “Europe cannot afford to give in to the separatists” by a Spanish conservative MP.

Young but talented with Master’s degrees to their name have looked down their nose and explained to anyone who cares to read, “Why Scotland and Catalonia Should not Become Independent in a Globalised World”. (She is not only prolific, but becoming more self-assured: her previous paper, published in November, was formulated as a question: Should Kosovo Become Independent?).

A selection of their more juicy statements would make a corpse blush:

“They [the Catalans] distort historical facts to justify imaginary grievances: they have transformed commemorations of the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714 into a denunciation of 300 years of “Spain against Catalonia.”

“[Since 1978], people from Catalonia have been able to develop their own identity while enjoying a degree of self-government similar to any state or province of any federal country, like the United States or Canada.”

“A veneer of respectability oftentimes hides the reality of the violent strands of the secessionist movement that plagues the streets of Barcelona. Pro-Spanish businesses that do not participate in the “human chains” or shows of force in favor of secession are many times attacked and boycotted, and any showing of the Spanish flag is brutally suppressed.”

“European history has taught us that unity means peace while nationalism and fragmentation leads to destruction.”

Some of these may well be more or less direct results of the intense activity of Spain’s diplomatic service, which has been disseminating its view of the process. At the end of 2013, the Spanish government sent all its embassies a flashy 250-page document “Por la convivencia democrática” which hammers Catalonia’s aims and calls for the rule of law and for coexistence within the framework of the Constitution, without offering any alternative at all.

The Catalan government replied, on February 12 2014, with a shorter document called ‘Estrechar lazos en libertad‘ in which it defends the democratic and historic legitimacy of the Catalans’ right to decide and asks the Spanish foreign minister to send it to all his embassies.

For its part, FAES, the Foundation of the governing conservative party, the Partido Popular, also jumped into the fray by posing 20 preguntas con respuesta sobre la secesion de Cataluña (20 questions with answers on Catalonia’s secession) in a publication… with a grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport!

Others – including non-Catalans – speak of Catalonia’s very real grievances, while the most prestigious newspapers and political magazines in the world fail to see why the Spanish government has not followed the path of the UK government and negotiated the conditions of the referendum. In parallel Catalan think tanks churn out and disseminate a host of good reasons for independence.

Yet what to the civilized world is a noble objective, for one’s nation to become sovereign by democratic means, is portrayed in our case as a step into the past (as if the number of independent nations had not greatly increased in the last 50 or 60 years). Catalans’ national aspiration to become free is compared with the ideologies of the most despicable of totalitarian regimes. And the most horrible, terrifying threat of all: that a free Catalonia would be hurled out of Europe. This is where Spain is concentrating its energies, as regards Catalan public opinion: the 30-point lead that the main surveys foresee for a Yes vote (55% to 25% of the electorate, with a further 10% of abstainers and 10% of “don’t knows”) would be reduced were Catalonia to be kicked out of the EU. This would apparently sway about one in ten voters to change their position, though even then the Yes vote would clearly win. The bombardment of this threat (which Spain has warned would be hasta el final de los tiempos: till the end of time!) has fostered the emergence of the view that joining the EFTA countries, with freedom of movement agreements with the EU, would certainly be a viable alternative, and would put an end to Catalonia’s current net contribution to the EU. Following a recent visit by European Commission Vice President Viviane Reding to Barcelona, a call was made to the European Union to make the referendum possible.

What is clear is Catalonia’s geostrategic importance in terms of road and rail traffic for freight, especially if its ports and trade with the Middle and Far East are taken into account.

I am not inviting the reader to take sides. I am simply trying to point out that the two sides in this cold war are like David and Goliath. The Spanish position, with immeasurably greater resources, is being broadcast throughout the diplomatic world, through all the Spanish media, through European Union officials being closely monitored by high-ranking Spanish officials so they don’t step out of the line. The disdain with which some of the latter treat the Catalan people has on occasion given rise to a popular response, and can be clearly perceived in this short video. And there is growing evidence that in some international circles, at least, the Spaniards are going too far in their quest to gain support for preventing the Catalans from voting. And in any case, Spain’s position is weakened by severe crises on several fronts.

The reader, then, is invited to read. And writers would do well to do the same, instead of taking insinuations, manipulations, and also lies at face value.

Spain has regarded Catalonia as a “problem” for as long as anyone can remember. But its long-standing failure to provide a suitable political framework in which Catalans could feel that they shared the State, instead of having it working against them, explains why the will for independence has grown so visibly in the last 15 years. And this growth has not been fostered by Catalonia’s political leadership, despite an insistent campaign by Spain and Spanish media. On the contrary, the grassroots swell, which became very visible in the unofficial local referenda on independence (2009-2011), clearly pushed the political leadership into an unprecedented decision: to put the country’s future in the hands of the people.

In 1921, Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset stated that “Spain is something made by Castile and there are reasons for suspecting that, in general, only Castilian heads have adequate organs to be able to perceive the big problem for the integrated Spain.” This hierarchical view of Spain is, in the last analysis, the root cause of the “Catalan problem.” For most Catalans, as we hope to be able to show, the solution is not a federation – noone in Spain has done anything in that direction, and despite David Gardner‘s sage advice in the Financial Times (March 6), any proposal to amend the Constitution would probably end up going in the opposite direction – but rather, a friendly handshake and good neighbourliness.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.