The European Union is looking for supply alternatives in order to reduce its energy dependence on Russian gas, particularly after relations between the West and Russia deteriorated following the Ukraine crisis.

One could say that relations between the EU and Russia are characterized as a paradox: both parties seem reluctant to abandon their energy relationship. To be more precise, the relationship is kind of symbiotic. The EU continues to be the best customer, constantly requesting more energy resources, and making the huge European market indispensable for Russia. Undoubtedly, suppliers and buyers constantly generate pretexts and arguments that ultimately aim to achieve better market placement, terms, and conditions.

Thus, we frequently see Moscow threatening an increase of gas prices or possible interruptions of gas supply to (or through) Ukraine. And the EU may again become a hostage of a Russian-Ukraine gas dispute (in January 2006 Russia cut off gas supplies only to Ukraine, yet the supplies of many European countries inevitably decreased as well).

In this context, the EU should actively consider strategies to reduce its energy dependence on Russia. Could the combined gas reserves of Israel, Cyprus, and Greece be an alternative solution for European energy demands?

As it stands, the EU is supplied with energy from Russia, the North Sea, the Maghreb Union, and the Middle East. The last two regions continue to be unstable due to political and social instability, extremist threats, and internal conflicts, while the aforementioned symbiotic relationship with Russia is troubling for Brussels. In this context, any alternative – provided that it is economically sound – is welcomed. Technically, the newly-found Israeli and Cypriot deposits are easily accessible to Europe as they can be carried by the large European-controlled fleet and not necessarily by pipeline. It seems that the three countries involved (GR, CY, and IL) can guarantee an uninterrupted gas supply to the EU, as they can provide a strategically secure energy infrastructure.

Greece’s Place in the EU Energy Picture

Greece has a unique opportunity to upgrade its energy profile, both in the short-term as a transit state and in the long-term as a producer state.

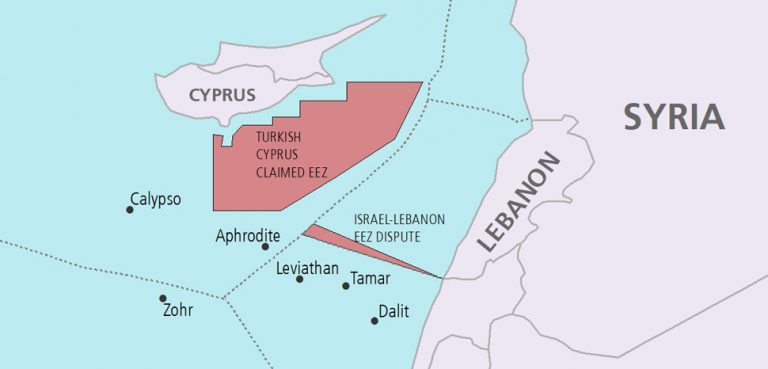

Both Cyprus and Greece constitute a significant, albeit underappreciated for decades, asset for European energy security. In March 2014, the government in Athens opened an international tender to assess the feasibility of a proposed pipeline connecting Israel’s Leviathan gas field to Europe via Greece. The proposed Eastern Mediterranean Pipeline will initially carry 8 billion cubic meters per year of Israeli and Cypriot gas. It will stretch from Israel’s Leviathan natural gas field to Greece, and into European markets through the IGI-Poseidon pipeline (shareholders Italian ENI and Greek DEPA). The philosophy behind this pipeline is simple: The EU requires reliable, secure, and domestic energy sources. Could this then become a concerted action within EU?

Apart from being a transit country, Greece could also potentially become an energy producer itself, should the estimates about its energy reserves in the Aegean, south of Crete, and Ionian Seas be officially confirmed. In 2012, a study conducted by the Athens-based Flow Energy estimated some €600 billion worth of offshore natural gas to be produced in Greece over the next 25 years, especially in the waters south of Crete. This study reveals geological similarities with the Levantine basin. Offshore Crete reserves are estimated to contain around 3.5 tcm (123.6 tcf) of natural gas, enough to cover over six years of EU gas demand, along with 1.5 Bbbl of oil. The only issue remaining is that Athens must declare its Greek Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the Aegean, Cretan, Libyan, and Cilician Seas in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The UNCLOS provides that a state has special rights over the exploration and use of marine resources, including energy production from water and wind. The EEZ stretches from the baseline out to 200 nautical miles from its coast.

Apart from being a transit country, Greece could also potentially become an energy producer itself

Cyprus, the second partner, wants to export gas reserves extracted from its “Aphrodite gas field” located at drilling block 12 in the country’s south maritime EEZ. The US-based main contractor, Noble Energy, has confirmed five trillion cubic feet (tcf) of natural gas, found in block 12, enough to transform the country’s long-term economic prospects. The European Commission also confirmed that Cyprus could play an important role in diversifying supplies. Whereas Cyprus has already demarcated its maritime border with Egypt (2003), Lebanon (2007), and Israel (2010), the overall scheme is negatively influenced, possibly impeded, by its long-standing rift with Turkey.

Israel, the third partner, has realized the importance of the discovery of 36 trillion cubic feet of gas off its coast in the eastern Mediterranean, mainly in the Tamar and Leviathan gas fields. Israel is a close ally of the United States; it has a powerful air force and is currently upgrading its navy. According to The Jerusalem Post, a senior naval source claimed that the Israeli Navy has started a program to improve its sea-to-surface missile capabilities. In addition, the Israel navy revealed that it will receive three new submarines. Two submarines will arrive in the second half of 2014 and another one in 2019.

Potential Competition from Turkey

The government in Ankara is promoting Turkey as a reliable energy partner which could help meet European energy demands. Yet, Turkey is not an energy producer, and its eastern provinces and borders are far from secure and calm. Moreover, the policies of Turkish PrimeMinister Tayyip Erdogan have given rise to serious concerns from some governments in the West, with some seeing shades of Ottoman imperialism in his rigid ruling style.

In this context, Turkey constantly flirts with a peculiar extremist Sunni, anti-Semitic, and anti-Israel agenda, while at the same time providing support to radical groups in Syria and Iraq (such as the ISIS/ISIL). Relations between Turkey and its neighbours are at a low point, especially with Israel, having suffered a significant setback (perhaps only the tip of the iceberg was seen during the Mavi Marmara crisis). Given the circumstances, it is very difficult to see the two countries rebuilding their old style alliance so long as Turkey supports Hamas and Sunni fundamentalists in Syria and beyond.

Conclusion

Greece should strive to upgrade its energy role by boosting cooperation with Cyprus and Israel. The European Union and the United States should promptly realize that this trilateral cooperation (Greece, Cyprus, and Israel) serves their geopolitical interests insofar that the European Union can gain access to new gas routes and reserves.

It would be only prudent for the European Union to enlarge its supply sources and at the same time encourage domestic (intra-EU) production. In this context, the Cypriot option is reasonable if it is combined with quantities produced in Israel and future production from Greece. Additional production will add to the EU energy portfolio and at the same time help to reduce prices over the long run. Oil and gas in the EU will also contribute to much-needed growth, job creation, and added expertise, all the while reducing inflation. The advantages are obvious. So why the delay?

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.