To Western observers, Russian President Vladimir Putin appears to be caught in a perfect storm: his gamble in Ukraine’s Crimea region has left diplomatic ties with the European Union as damaged as they’ve ever been, with Russia losing the support of a critical ally in Germany; the ruble has dropped 22%, which has helped Russia post its slowest GDP growth in five years; and slumping oil prices could cause the Russian economy to lose between $90 billion and $100 billion per year if oil prices drop more than 30%, according to Russia’s Finance Minister Anton Siluanov.

Russia’s economic difficulties are unlikely to be resolved in the near future, especially considering the lack of potential for regime change. Putin has been in power, either as president or prime minister, since 2000, and has, since reworking formerly independent media voices like Ria Novosti into state-controlled propaganda machines, been riding high in the polls with approval ratings near an all-time high of 86%. Earlier this week, he said he would not be in power for life and would likely step down no later than 2024, in accordance with the Russian constitution. The announcement was met with deep skepticism across the board.

Despite the economic gloom, and the growing criticism from Russian oligarchs who have lost tremendous amounts of capital as a result of the economic downswing, Putin is determined to push ahead with what many assume to be his pet project: the reconstruction of the Soviet Union, or at the very least, bringing “lost” territories back into the fold of Russian domination. This policy takes the form of the burgeoning Eurasian Economic Union, itself an outgrowth of the Customs Union first implemented by Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus in 2010.

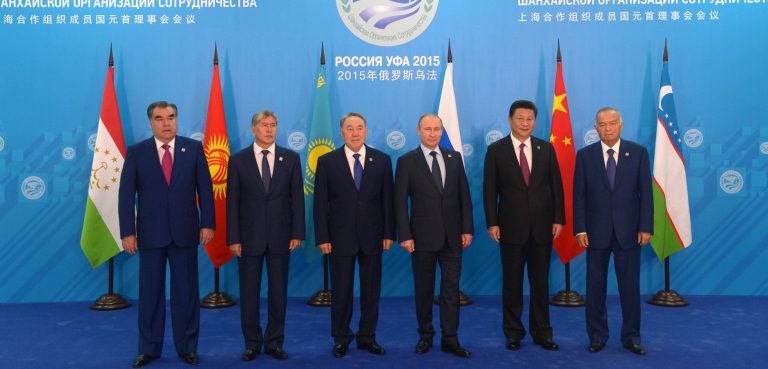

“The Kremlin’s maximum goal has been to secure recognition of this [post-Soviet] area as its legitimate sphere of influence that gives Russia a droit de regard over its former republics,” University of Kent Professor Richard Sakwa wrote in Power and Policy in Putin’s Russia (2013). Though the region has become increasingly involved with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (with China) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (with Russia as the leading member), “bilateral ties remain the Kremlin’s priority.”

However, Russian involvement in Ukraine earlier this year is making many, if not most, post-Soviet states nervous. If these governments had been formerly disinclined to view the Eurasian Economic Union as a ploy by Putin to re-attach former Soviet territories, some are visibly nervous about it now.

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, a member of the tripartite Customs Union with Russia and Belarus, at first welcomed the idea of the partnership, telling its population that it would increase the country’s domestic market from 16 million to 180 million. As the argument went, Kazakhstan needed to diversify away from oil and gas and develop its manufacturing sector. Increasing the number of potential customers could only result in progress on these fronts.

However, the early outcome of the customs union has been Russian goods flooding into the Kazakh market, making it even harder for Kazakh producers to compete. According to a September 2013 op-ed from the Peterson Institute for International Economics, the sharp increase in customs tariffs meant that Kazakh customers were compelled to buy sub-par Russian automobiles. The Peterson Institute estimates that joining the customs union will cost Kazakhstan the equivalent of 0.2% of its GDP.

Kazakhstan is also suffering from sanctions imposed on Russia by the EU over the ongoing crisis in Ukraine. In September 2014, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development said that “growth [has] slowed down” in Kazakhstan due to “the impact of oil project delays”, though Kazakh food exports grew to replace food imports from EU countries in Russia.

Nursultan Nazarbayev, the president-for-life of Kazakhstan, is also concerned about Russian incursions into the vast country – itself the size of Western Europe. Earlier this month, Nazarbayev called on Kazakhs to strengthen their unity and maintain “inte-rethnic harmony.”

Nazarbayev is mindful of Putin’s pledge in July to protect all Russians abroad.

“I would like to make it clear to all: our country will continue to actively defend the rights of Russians, our compatriots abroad, using the entire range of available means— from political and economic to operations under international humanitarian law and the right [of compatriots abroad] to self-defense,” Putin told Russian ambassadors and government ministers at a July 1 meeting at the Kremlin.

Ethnic Russians account for around 23% of Kazakhstan’s small population, and Nazarbayev is eager to fend off any intimation that ethnic Russians are unwelcome in the country, lest he incite a desire in Putin to annex Kazakh territory.

Kyrgyzstan

Russia has been circling Kyrgyzstan since 2001, when the United States established a military base in the country to ferry soldiers and material into and out of Afghanistan for military operations against the Taliban. Moscow took great umbrage at the US presence there, feeling that the country dared to impinge on Russia’s traditional ‘sphere of influence.’ Though corrupt Kyrgyz politicians needed little push to periodically increase the United States’ rent on the airbase, Russia exerted further pressure on the government to eject the Americans. The United States finally vacated the base in June earlier this year.

Kyrgyzstan has also increased its reliance on Russia for energy, after Gazprom paid $1 to take over national gas provider Kyrgyzgaz in June. The tiny Central Asian state has long had difficulty in meeting energy demand during its long winters, causing much of the country to deal with prolonged blackouts and stifling industrial development. However, Uzbekistan opted to halt gas exports to Kyrgyzstan shortly afterwards, which has left local Kyrgyz relying on wood and other energy sources in the meantime.

Pressure to join the EEU by Moscow has also met with an at-best lukewarm reaction from Kyrgyz politicians, who are concerned that eliminating customs duties will flood the Kyrgyz market with foreign goods. Joining the economic union would also require Kyrgyzstan to increase tariffs on Chinese goods, which would bring an end to the ability of many Kyrgyz merchants to resell these goods at a profit. However, Russia has promised to write off the country’s $489 million debt, as well as work on building up Kyrgyzstan’s hydropower network, if Bishkek agrees to join the EEU.

Earlier this week, after months of hesitation, Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambayev agreed to begin the accession process to the EEU, saying, “We’re choosing the lesser of two evils. We have no other option.”

Tajikistan

Tajikistan – the poorest state in both Central Asia and of all the former Soviet states – suffers from a weak economy wrought with corruption and nepotism, with a significant chunk of state-owned industries owned by cronies of the long-serving president, Emomali Rahmon. The economy is heavily dependent on remittances from Tajiks working as migrant workers in Russia, with Tajikistan topping global tables for the highest dependence on remittances in the world. Over 50% of the country’s GDP depends on remittances, and Russia periodically threatens Tajikistan with barring Tajik workers from entering the country.

In April, Moscow imposed a new law requiring migrant workers to know the Russian language, as well as be familiar with Russian laws and history. Many Tajik migrant workers do not possess these skills. As of Jan. 1, 2015, Tajiks will no longer be able to enter Russia with a domestic passport and must instead hold an international passport or similar document, as part of Moscow’s latest attempt to limit the number of migrant workers from the CIS.

Tajikistan also struggles with policing its 800-mile border with Afghanistan, and continually has difficulty with extremists both outside and inside its mountainous territory. Tajik border guards are ill-equipped to contend with violent jihadis and drug runners, while Russia and the United States were recently in contention in trying to assist the Tajik military with policing the border. A Nov. 6 meeting of CSTO in Moscow focused on the need to improve security on the Tajik-Afghan border via cooperation between Russia and Tajikistan.

Russia continues to push for Tajikistan’s accession to the EEU. Russian parliamentary Upper House speaker Valentina Matviyenko declared on Oct. 24: “Our Tajik counterparts are examining conditions for possible membership and we very much hope they will eventually join the EEU.”

Both Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are WTO members, and accession into the trade body would most likely force them to double their tariff barriers and thus violate commitments to the world trade body, Nicu Popescu points out in a September 2014 report for the EU Institute for Security Studies. Neither Kyrgyzstan nor Tajikistan is particularly enthused about joining – but both face substantial negative repercussions if they fail to sign on.

Turkmenistan

Russia is unlikely to expend much energy in trying to bring Turkmenistan, the isolationist desert country bordered on one side by the Caspian Sea, on board for the regional economic union. Relations between the two countries soured definitively after an explosion on the Turkmenistan-to-Russia gas pipeline in April 2009, after which Russia opted to import only one-third of the gas it had prior to the explosion. Turkmenistan sits atop some of the largest gas reserves known worldwide, and its economy relies nearly exclusively on proceeds from gas sales.

A battle over Turkmenistan’s telecommunications industry ensued in 2010, when the Turkmen government revoked the operating license of MTS Turkmenistan, a subsidiary of Russian mobile operator MTS. The scuffle cost the company $140 million before Turkmenistan re-instituted the license, with MTS now being forced to pay 30% of its net profit each month to the Turkmen government.

Now that Russia’s Gazprom has increased production, it has decreased its reliance on Central Asian, and by extension, Turkmen, gas. Turkmenistan’s economy remains largely un-diversified, so benefits accruing to Turkmenistan’s inclusion in the Eurasian Union project would be minimal.

Ashgabat has also been working to launch a trans-Caspian pipeline which would provide significant amounts of gas to Europe, and thus aid Europe in cutting down its gas dependence on Russia – a move which continues to anger Russia. Moscow has staunchly opposed Turkmenistan’s involvement in negotiations with the EU over the Nabucco and Trans Caspian Pipeline in the past.

Neither project has continued, though Turkmenistan is actively working to diversify its natural gas customers. On November 7, Turkmenistan inked a deal with Turkey outlining a framework agreement for the Trans-Anatolian natural gas pipeline project, which would transport Turkmen gas to European customers.

Turkmenistan has also, since 1995, operated under a policy of international neutrality, which precludes it from participating in such an interstate agreement. The country has not ratified the Commonwealth of Independent States charter and is not a member of CSTO, making its participation in Russia’s new project extremely unlikely.

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan has strived to keep its distance from Russia, despite Russia being its largest trading partner. Lifelong Uzbek leader Islam Karimov is deeply convinced that Uzbekistan is the strongest state in Central Asia, and refuses to cooperate in multilateral institutions like CSTO which would put Uzbekistan on a level playing field with the small, weak states of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Uzbekistan was an inconsequential member of CSTO, and often refused to participate in meetings and training drills. In 2012, it officially left the organization.

Tashkent is also unafraid to turn its back on Russia and work with Russia’s competitors. When the United States needed a Central Asian air base to facilitate military operations in Afghanistan in 2001, Uzbekistan was eager to offer its Karshi-Khanabad (K2) airbase for those purposes. However, following the 2005 massacre in Andijan which is believed to have resulted in the deaths of hundreds, Uzbekistan expelled the US forces from the base over American criticism of the regime.

Karimov’s preoccupation with maintaining Uzbekistan’s sovereignty has been jolted by events in Ukraine. At the UN in March, Uzbekistan abstained from voting on the status of Ukraine’s referendum. In September at an SCO meeting in Tajikistan, Karimov called on Russia and Ukraine to negotiate – openly asserting that Russia is implicated in the Crimean debacle. In the meantime, Uzbekistan has thrown its support behind China’s Silk Road economic belt to stimulate bilateral trade with each of the Central Asian states.

Chinese influence – causing Russia to be pushed out?

Russia has a major competitor in the region – China. In May, China unveiled its ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ plan, which involves spending $16.3 billion to bolster trade routes between China and the Central Asian republics, via land and sea.

The plan envisages the construction of airports, ports, railways and roads throughout the region, Chinese President Xi Jinping said in November.

Chinese trade with Central Asia is immense, valued at $46 billion per year. China is the largest trading partner of all Central Asian states – minus Uzbekistan – and received over 50 million tons of crude oil since 2006 via the China-Kazakhstan oil pipeline. By 2020, the China-Central Asia pipeline, will account for 40% of all of China’s imported gas.

Central Asian states find it much easier to get on with Beijing than with Moscow, because Beijing never interferes with politics or attempts to strong-arm states into accepting policies against their will. For the moment, China is eager to build up its trade relations with these states, but whether it will displace Russia as a dominant force in the region is an open question.