Alliance-formation among terrorist groups is not an unusual practice and cooperation between two or more terrorist groups can be formed as a result of practical and ideological needs and interests. Even if groups are often geographically distant and engaged in either unrelated or different types of conflict, terrorist groups identify “operational effectiveness,” tactical and strategic range, “efficiency,” and even “enhanced legitimacy and stature” as the primary reasons for allying with one another.

African Islamist movements have generally faced internal volatility and disorder, with northern Mali being the typical example of a loosely formed alliance that quickly falls apart. Such an outcome can be possibly be avoided by affiliating oneself with a powerful ideological partner such as ISIS, thus helping bind members to the cause.

Terrorist groups, though able to see positive aspects of working together, do not always foresee the challenges brought forward through partnering. Tricia Bacon, author of Strange Bedfellows of Brothers-in-Arms: Why Terrorist Groups Ally, explains that, “[t]he prevailing notion that terrorist groups with shared enemies or ideologies will naturally gravitate toward one another mischaracterizes the nature of relationships among these illicit, clandestine, and violent organizations.”

Grievances, rather than common political visions, can also bind terrorist groups together. In the case of ISIS, as long as the group maintains a very decentralized role, it will be an attractive ideological choice for many differing Islamist groups. The timing of terrorist partnering, the duration of alliances, and the degrees of cooperation between them are all difficult variables to predict and explain. Despite pledges of allegiance made by leaders of terrorist groups, there persists a need to consider a wide spectrum of factors and conditions in order to diagnose the authenticity, robustness, and probability of success in terms of alliances between terrorist groups.

The Sinai-based Egyptian extremist group Ansar Beit al-Maqdis’ (ABM) pledge of allegiance to ISIS in late 2014 triggered precisely these questions (others have come from groups active in Libya, Algeria, Yemen and Saudi Arabia, and militants in Afghanistan and Pakistan have declared their intention to form provinces of ISIS). Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’Awati Wal-Jihad’s (otherwise known simply as Boko Haram) audio pledge (posted on the group’s Twitter account by [what appeared to be] the group’s leader) raises these questions once again.

Veryan Khan, editorial direction of the US-based Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium (TRAC), recently claimed that, “Boko Haram is not a mere copycat of ISIS; rather, it is incorporating itself into the Islamic State.” The statement comes at a critical point in determining the alignment of the Boko Haram in formal terms, yet the group has shown many signs of adherence to ISIS previously through symbolism such as flags and other signs within its media presentations. And in turn, supporters of ISIS began referring to Boko Haram as “Islamic State Africa.”

Like ISIS, Boko Haram has demonstrated a strategy that seeks the creation of a caliphate like the one ISIS claims to have established. Boko Haram’s media techniques and operational brutality strongly resemble those of ISIS. But does this make the claim of allegiance significant? And if so, how sustainable is partnership?

ISIS’ original declaration of “the caliphate” contested the independent authority of emirates, states, and other groups and organizations. Thus a notable friction point should be considered regarding the potential formation of Boko Haram’s own caliphate in Africa. The outcome of two caliphates forming or the implications of Boko Haram recognizing or not recognizing the one already formed by ISIS will constitute a critical juncture in their relationship.

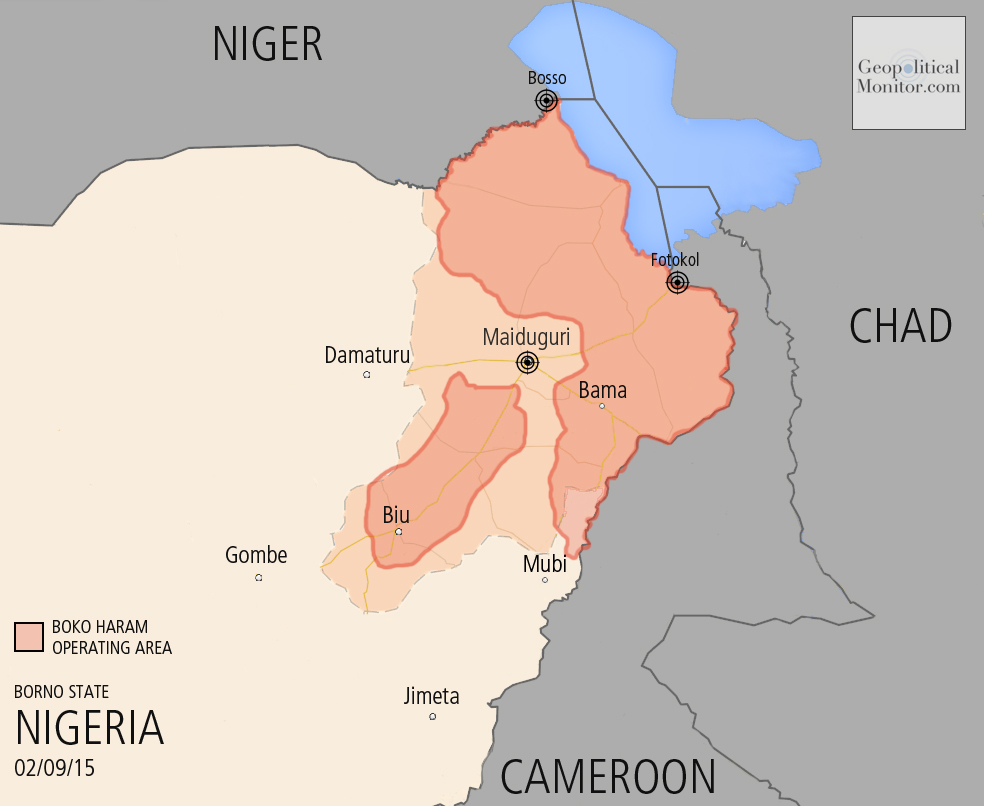

Boko Haram has attracted many fighters to its cause, but it has also alienated much of the general population from which vigilantes fighting against the group have emerged. It has also alienated many within the rank and file, leading to breakaway factions. In 2012, speculation arose over the formation of the new militant outfit from Boko Haram calling itself “Ansaru.” That group formed and operates today as Jama’atu Ansarul Muslimina fi Biladis Sudan (JAMBS – Ansaru) (“Vanguard for the Protection of Muslims in Black Africa”). Ideological differences and conflict resulting from differing interpretations of Islamic law promulgated the split with Boko Haram.

Ansaru seeks the re-establishment of a Muslim state similar to the historical Sokoto Caliphate founded by Usman dan Fodio in the 19th century. Ansaru has openly stated its intent to target Western nationals and interests within their areas of operation, who are believed to be either directly or indirectly supporting military operations against regional and/or international Islamist militant groups. As new groups emerge, competition rises over foreign fighters – something that Boko Haram has not been terribly successful when compared to ISIS. One should not rule-out the possibility that Boko Haram’s pledge to ISIS is entrenched in pragmatic needs like training and other forms of indirect assistance.

ISIS has reduced its operational capacity by expanding its enemy-base in the Middle East. As countering immediate opponents has taken precedence, it has found itself unable to offer considerable support to groups attaching themselves to ISIS. This logic can be extended to Boko Haram. Turf wars and territorial claims are also likely to become increasing divisive mechanisms among BH, ISIS, and others. The case of the Yemeni-based al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) lends sympathy to this line of argumentation. As Professor Mark N. Katz notes: “[AQAP] criticized ISIS in November 2014 when the latter claimed Yemen as part of the caliphate that ISIS aspires to rule.”

Establishing precisely how ISIS views Boko Haram is a difficult task, and one level of “acceptance” within the organization does not mean the same exists at the lower levels. It might be apt to assume that a large number of fighters in ISIS by default have an inimical outlook on Boko Haram. “A US intelligence officer” according to Breitbart, “told NBC News the Islamic State (ISIS/ISIL) will not likely team up with Nigerian radical Islamic group Boko Haram in any official capacity due to the group’s racism against black Africans.”

African-Americans have the potential of presenting themselves as somewhat of a resource for ISIS. Events that took place in the US town of Ferguson in 2014 captured the attention of ISIS leaders who see the conflict as a potential propaganda and recruiting tool. Souad Mekhenet points out that various social media platforms started carrying the hashtags “#FergusonUnderIS” and “ISISHERO.” “The Islamic State and other jihadist movements,” according to Mekhenet, “are using events outside St. Louis as propaganda against the West. One argument they’ve been making for years is that racism and discrimination are rampant in some parts of the West, and they’re hoping the Ferguson riots could help recruit black Americans.”

Looking to the West for disillusioned, particularly young African-Americans, who are willing to subscribe to extremist ideologies overseas, undermines Boko Haram by attempting to recruit from sources from which its own operations would also benefit. In 2014, Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekaau also noted the so-called ‘opportunities’ presented by frustrated American males overseas. These Islamist groups are all vying and bidding for the same support, which inevitably breeds friction between them.

The acceptance of pledges – which has the potential to alter the self-perception of ISIS, compelling the group to view itself as the “core” of a terrorist coalition defined by a shared ideology – is also problematic. Ideological foundation is sought in order to better overcome internal frictions. Such frictions rarely survive a serious face-off with an opponent, since most fighters join such organizations in order to find alternative financial resources, including through narcotics, people trafficking, kidnapping, and theft.

Implications could also be found in the relationships between dominant Western nations (particularly the United States [US], the United Kingdom [UK], and France) and Nigeria, in particular after Roman Catholic Archbishop Jos criticized the West for ignoring the sub-Saharan conflict, including Nigeria’s ongoing battle with Boko Haram. The exchange, which also included US counter-criticism against the Nigerian government for its response to the terrorist group, led to the Pentagon’s principle director for African affairs, Alice Friend, to assert that, “[i]n general Nigeria has failed to mount an effective campaign against Boko Haram.”

Expectations could emerge that the West increase its activities in sub-Saharan Africa in response to the recent pledge of allegiance by Boko Haram. If this happens, two potential recoils could take place. On one hand, the West, in response to both calls by Nigeria to become involved and pressure due to the supposed partnering between Boko Haram and ISIS, could move beyond soft-involvement such as training and advisory programs. Such a response could legitimize both the group and its pledge. On the other hand, inaction (or at least restrained commitment/involvement) might inadvertently validate the claim that the West sees sub-Saharan conflict as of secondary importance.

With increasing ties between Boko Haram and other terrorist groups like ISIS and al-Qaeda (AQ) (via indirect assistance), questions will surely mount regarding the willingness and capacity of Western (i.e., US, European Union [EU], United Nations [UN], and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization [NATO]) security structures to deal with this growing terrorist threat.

In October, 2014, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, working with the UN Assistance Mission in Iraq, publicized a report stating that ISIS has killed roughly 8,493 civilians, began recruiting 12- and 13-year-old soldiers, implemented a “convert or die program,” and engaged in sex-slave operations involving girls and women. Perhaps the most practical concern to stem from the recent pledge by Boko Haram relates to the possible extent to which the group, as well as others like it operating elsewhere, will attempt to mimic the policies of an expanding ISIS to the north.