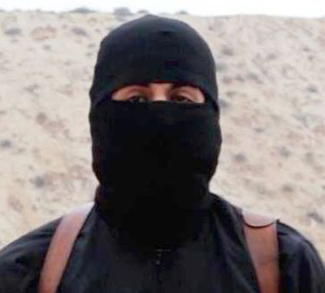

He has been at the forefront of Islamic State’s (ISIS) brutal execution videos in recent months. The masked man behind the decapitation of several high-profile hostages including US journalist James Foley, British aid worker David Haines, American aid worker Peter Kassig, as well as Japanese journalist Kenji Goto has now been identified as Mohammad Emwazi, a Kuwaiti-born British man.

Reports from both the Washington Post and the BBC said the man in his mid-20s, more commonly known as ‘Jihadi John,’ is from west London and had been put on a terror watch list and banned from leaving the UK. Scotland Yard has refused to comment citing an ongoing investigation.

The revelation of Jihadi John was just one of many stories of radicalization among those living not only in the Western world, but across the globe. It is not a new phenomenon and there have been many similar stories in the past where citizens from one country slipped through their national borders and joined an armed struggle abroad.

The troubling development of the past few years however is that the rise of ISIS comes amid a rapid growth of social networking sites, which can reach millions worldwide – including those in Southeast Asia.

Evidently, legal options by national governments have been limited in curtailing potential jihadists. The same can be said of surveillance by intelligence agencies engaged in the difficult task of monitoring each individual who has the tendency to become radicalized. From the Sydney café siege to the shooting at the Cultural Centre in Copenhagen, all of these events have simply highlighted that the process of radicalization knows no boundaries and can transpire even from the comfortable seat of a person’s home.

The presence of the internet might not be the sole factor that radicalizes a person, but it has definitely created more opportunities for one to access materials related to their extremist beliefs. A report titled “Radicalisation in the Digital Era” by Rand Corporation published in 2013 highlighted that while radicalization is very unlikely to occur without some forms of physical contact with the organization itself, it however can act as an ‘echo chamber’ that confirms one’s radical beliefs.

For ISIS, the internet is an opportunity for it to reach out to those who would join its cause and establish a caliphate in the Middle East. In many parts of Southeast Asia, this online campaign has already gained traction; countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines where there is a significant Muslim population. Southeast Asia itself is no stranger to global terror with groups such as Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) and later Jemaah Ansharut Tauhid (JAT), as well as Abu Sayyaf that remain active in countries like Indonesia and the Philippines. These groups are believed to have pledged allegiance to ISIS recently.

While ISIS has a priority in consolidating its control over territories in Iraq and Syria, it is also interested in intensifying its global recruitment campaign by attracting extremists worldwide to be part of the jihadist movement. Through propaganda videos that glorify the leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and the role of foreign fighters, ISIS has undoubtedly ‘conquered’ social media by capitalizing on its borderless nature to recruit and gain financial support. Any analysis of ISIS videos reveals that the organizations PR machine is highly sophisticated and most of the time targeted at a specific audience.

For example, ISIS supporters had in September last year released a video on YouTube that modified top videogame franchise, Grand Theft Auto V by allowing players to play as a militant, killing police officers and blowing up military trucks. Egyptian media said the video was aimed at raising the morale of Mujahedeen and attracting young teenagers to fight the West.

The case of Jihadi John stands out as a foreign fighter from the West who has been radicalized by the group, and at the same time able to instil fear into millions by executing Western hostages on air. It is worth noting that the name “Jihadi John” was given by the British press rather than ISIS itself.

Despite this, the name has already gained notoriety in the British public in its suggestion that the person next door, regardless of education or financial background, could become radicalized. According to various media reports, Emwazi lived a largely normal student file until 2009 when he traveled to Tanzania, reportedly attempting to join al-Shabaab in Somalia. He was refused entry in Dar Es Salaam. Upon returning to the United Kingdom, Emwazi claimed that he had been “harassed” by intelligence officials numerous times until his sudden disappearance in early 2013.

There have been significant debates concerning the process of radicalization among academics and policymakers alike, though none has been able to provide a conclusive explanation beyond some general observations.

Some have claimed that radicalization can take place particularly among those from a lower or lower-middle class socio-economic background – people who live in relatively bad neighborhoods and are frustrated with the present system and their position in the society. But isolation and alienation are not necessarily a precondition, as seen in some cases where those from well-off families join the jihadist movement. A conclusion provided by a 2008 research report entitled “Radicalisation, Recruitment and the EU Counter-radicalisation Strategy” stated that radicalization is not a result of independent factors but instead a complex interaction of external factors, namely the political, economic, or cultural conditions that shape an individual’s behavior.

Radicalization in the Southeast Asian Context

In Southeast Asia, radicalization by ISIS presents a two-fold security challenge to governments in the region. With extremist groups such as those in southern Philippines and southern Thailand claim that their people have often been discriminated due to ethnicity, ISIS’ propaganda is a further conviction that those who want “to do something” should take up arms and fight their governments. These groups such as the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) and Abu Sayyaf rebels in southern Philippines that quickly pledged allegiance to ISIS are also riding on its growing popularity in the Middle East as a way to inspire locals to be part of their own causes.

Apart from local groups, ISIS is also keen to recruit fighters from this region to join its cause in the Middle East. It is estimated that as many as 200 Indonesians and 40 Malaysians have gone to fight in Iraq and Syria with another report in September last year pointing out that ISIS has formed a Malay-speaking unit among its ranks. In May 2014, Ahmad Tarmimi Maliki became the first Malaysian suicide bomber for ISIS after he drove his SUV laden with explosives into the Iraqi SWAT headquarters in Anbar.

Numerous reports have also claimed that Malaysia has been used as a transit point for militants from Indonesia before joining ISIS in Syria. Local newspaper The Star reported that ISIS has issued a warning in early January for recruiters to avoid using Malaysia as a transit point amidst a heavy police crackdown there.

The challenge of returning fighters is equally daunting as trying to prevent someone from heading to the Middle East. This is because once returned, they might bring back their armed struggle and ideology, starting local divisions of ISIS and waging a war against governments in the region. Such an attempt was seen last year when the Malaysian police detained 19 suspected militants who planned to bomb a Carlsberg factory in the outskirts of the capital, Kuala Lumpur.

All these have presented challenges to regional security services that are keen to prevent more bloodshed amidst the rise of Islamic fundamentalism over the past decade. ISIS is a dynamic group and this means the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) governments need to take more proactive measures through increased co-operation so that its rise can be curbed.