The shift in demographic and economic weight from Europe to East Asia has intensified over the past 20 years, which makes East Asia and its coastal areas increasingly important – a critical shift in current and future international relations dynamics underscored by the United States’ (US) “Pivot to Asia” or East Asian foreign policy of the Obama administration. Four Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) members, plus China/Taiwan either partially or fully claim sovereignty over the South China Sea and its territorial features: islands, reefs, and atolls. Given the importance of the South China Sea’s islands and sub-soils, we seek to assess whether a Chinese policy towards the South China Sea’s territorial disputes endangers regional stability and cooperation.

Economic and Strategic Importance of the Spratly Islands

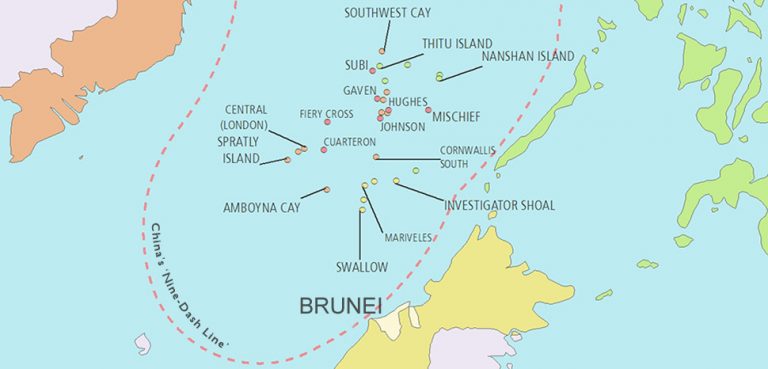

China’s extensive borders, surrounded by sea and a rich diversity of neighbors, from large Russia, unstable Afghanistan, to maritime neighbors such as the Philippines, South Korea, and Japan, presents a host of security challenges. The South China Sea forms part of the complexity of China’s border security challenges. The following claimants surround the South China Sea: China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and the Philippines. Territorial disputes contribute to regional volatility. The Sea is considered a flashpoint for conflict in the Asia Pacific Region. There are two groups of islands in the South China Sea: the Paracel and Spratly Islands. China, Taiwan, and Vietnam claim all of the Paracel and Spartly Islands, while Malaysia, the Philippines, and Brunei only claim parts of the Spratlys. Claims put forward by China, Taiwan, and Vietnam are historically based, whereas claims made by Malaysia and Brunei are based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLoS), the proximity principle, and the continental shelf principle. The Philippines’ claim is based on proclaimed discovery of unclaimed islands in 1956.

Disputes in the South China Sea are exacerbated by the economic and strategic importance of the area. The emergence of China as a major economic and military power resulted in sharp increases of consumption of energy resources for industrial growth, creating an increased international trade of minerals and manufactured goods. China’s hunger for natural resources thus, largely rests on its dependency on energy and mineral imports. The majority of Chinese imports and exports use South China Sea lanes for transportation. Therefore, it is in China’s interest to secure the region in order to ensure a continuous movement of goods into China. Put differently, China seeks to dominate and control the South China Sea for securing its trade interests, exploring natural resources under the seabed, and politically dominating East Asia.

Strategically, the passageway in the South China Sea connects North and East Asia with Gulf countries and the world in terms of trade, particularly the import of crude oil, which is critical to economic development (especially for aspiring or rising powers in the region) (Rousseau, 2011). Not only is this passageway the world’s busiest sea route, transporting two-thirds of global oil supplies, the South China Sea also connects the US and its allies in Northeast Asia, which serves as a strategic transportation route and a communication channel for its commercial and military interests (Dillon, 2011). The importance of this area thus, creates a dual necessity for all players, especially China: (1) Gain control of the region’s resources. (2) Maintain security/stability so that economic growth can go uninterrupted.

China’s Foreign Policy, Contradictions, and Unpredictable Actions

Despite some military incidents that have bred instability, China’s foreign policy, as per their Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), focuses on the principle of China’s “independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity, to create a favorable international environment for China’s reform and opening up and modernization construction, maintain world peace and propel common development.” This reflects a need for stability and security in the region by encouraging harmonious neighborly relations, mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, mutual non-interference in internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. Furthermore, China claims to actively facilitate the establishment of a new international political and economic order that is fair and rational. It takes an active part in multilateral diplomatic activities, preservation of world peace and facilitation of common development. As well, it promotes consultation and peaceful resolution of disputes and conflicts between the countries and without the use or threat of force. It is clear that all these statements reflect a need for stability and security in order for economic development to continue uninterrupted.

Yet, over previous decades China’s foreign policy has been tested on many issues at different stages, making China’s actions rather unpredictable. These tests range from China’s democratized foreign policy, meaning that voters are increasingly demanding certain policies, to internal influence of xenophobic nationalism demanding more aggressive policies on global issues. China’s high running nationalism can promote more aggressive policy in the South China Sea, as China rises as a global economic, political, and military power. These contradictions constraining China’s foreign policy combine with China’s aspiration to be a global power, but its failure to adopt the responsibilities of a major power. Namely, China aspires to see the global integration of its economy but emphasizes its sovereignty and reluctance over interference in its internal affairs. This reluctance is also visible in Chinese government’s suspicion of multilateralism and a strong preference for bilateralism. China is also against any third party interference or mediation in the South China Sea dispute and has always been successful in sidelining the issue of territorial dispute and militarization of the disputed area at multilateral forums like ASEAN. Instead, it has put forward bilateral and peaceful solutions, while at the same time asserting its undisputable sovereignty over the South China Sea and also heavily investing in military modernization, as well as constructing structures for military use in disputed areas.

China’s Relations with Claimant Countries and ASEAN

China and Vietnam are the two major contenders in the South China Sea dispute and they have clashed several times over the occupation and control of islands in the region; both countries assert historical claims over the Paracel and Spratly Islands. Vietnam originally sought help from ASEAN to counter China’s power, thus endorsing ASEAN’s declaration on the South China Sea for multilateral discussions on territorial disputes. The Mischief incident in 1995 encouraged Vietnam to invite the US into mediation talks in the dispute settlement. At the same time, China and Vietnam also held various bilateral negotiations with the aim of resolving the disputes by “mutual understanding and accommodation and the spirit of friendly consultation” and “international law and international practices.” In 2000, both countries successfully negotiated and agreed on the demarcation of the Gulf of Tonkin, part of the South China Sea. Despite the success of several diplomatic talks and negotiations, both countries are actively involved in unilateral activities that have resulted in several skirmishes and protests on both sides. Vietnam, one of the new ASEAN members, is China’s traditional adversary. They have fought on several occasions on land and at sea. In 2008, both countries made a joint declaration for efforts to safeguard stability in the South China Sea and restrain from action that would complicate or amplify the dispute. However, both countries again became involved in a diplomatic dispute in 2009 after Vietnam appointed a governor for the Paracel Islands.

The dispute between the Philippines and China began in 1995 when China started building structures in the Mischief Reef near the Philippine’s island of Palawan. The Philippines blamed China for building a shelter for the military, while China claimed that the structures serve as shelter for fishermen. Both countries signed a code of conduct to avoid similar future incidents, but the situation remains tense with a flaring of disputes. The Philippines, after ending its military leases to the US in 1992, extended its military lease after China’s growing power led to deep feelings of insecurity. The Philippines continuously raised the South China Sea dispute at many multilateral forums and has also endorsed the China-ASEAN declaration on the code of conduct of parties. China-Philippines relations improved in 2005 after both countries signed a tripartite agreement with Vietnam for oil exploration. Both China and the Philippines experienced a “golden age” of partnership. It ended in 2009 when the Philippines passed a new law that asserts their claim over the disputed Spratly Islands. China immediately dispatched a diplomatic protest against this action and also sent a patrol boat to the area.

Malaysia is one of the four occupant countries of the Spratly Islands, including China, Vietnam, and the Philippines. China protested, asserting its claims, when Malaysia built tourist and military facilities on the occupied features. Malaysia initially expressed concern over the assertiveness of China’s position in the Spratly Islands, which was backed by Chinese naval presence in the area. Malaysia also felt vulnerable in the wake of growing Chinese power because of past experiences with Communist insurgency. This is only exacerbated by the fact that one third of the Malaysian population has Chinese roots. However, several mutual visits, to increase political and economic cooperation, followed by a military cooperation, have built strong(er) relations between the two countries. Malaysia also supported the Chinese view of bilateral negotiations to resolve the dispute over the Spratly Islands and thus, has expressed doubt over a multilateral approach by suspecting further complications. Both countries progressed with a bilateral approach and have built strong political, economic and military ties. Malaysia is convinced of China’s seriousness in a peaceful resolution of a dispute over Spratly Islands and is also working towards a joint development in a disputed territory. Furthermore, Malaysia and China issued a joint communiqué for strategic cooperation, enhanced bilateral consultation, and cooperation; Malaysia has also reaffirmed its support of the “One China Policy.”

ASEAN is the main multilateral forum in the East Asia region. It acts as the main platform for a peaceful resolution of the South China Sea dispute and it is seen as being helpful in countering the rise of China’s economic, political, and military power – a major concern of smaller (and weaker) countries. ASEAN members have at many times raised concern in various forums and meetings in support of a multilateral approach for the peaceful settlement of the South China Sea dispute, but China remains skeptical of the multilateral diplomacy approach and thus, is reluctant to address the issue at such forums. ASEAN, however, has to be careful to not look as though it will abandon its previous postures of accommodating Chinese because of China’s assistance to ASEAN members during the recent economic and financial crisis. These countries do not want to jeopardize their relations with China and believe that China will act more positively by demonstrating a greater degree of self-restraint in a dispute over the Spratly Islands. ASEAN also provides an opportunity to its members to discuss their concerns related to the South China Sea on the sidelines, which is also known as “quiet diplomacy” or the “ASEAN way.”

US Involvement or Interference?

Countries like the Philippines and Vietnam, which considered their positions vulnerable as a result of Chinese military power, were trying to internationalize the South China Sea territorial disputes by seeking active US involvement. The aim was simply to counterbalance China’s growing military power, which has taken place over the past two decades. Although the US should not be too worried about losing its military advantage due to its advanced technologies, China occupies a very comfortable position in terms of its strategic relations with Southeast Asia. In 2010, the US stepped in by declaring its national interest to ensure the freedom of navigation, unrestricted access to Asia’s maritime commons, and respect for international law in the South China Sea region. The US seeks a multilateral diplomatic process by all claimants to resolve the various territorial disputes without the threat of force or the use of force. China, on the other hand, has always opposed interference of non-claimant countries like the US, which has resulted in the deterioration of US-China relations. The US supports multilateral dialogue for dispute resolution and it expressed an interest in active participation in open and frank discussions over territorial disputes. This was a result of a new policy of reengagement in Asia that sought to restore its image and clout by showboating its alleged interests in safeguarding the interests of smaller and weaker nations via diplomatic and military influence.

China’s “Behavior” in Recent History

Since the 1990s, China has campaigned for its “peaceful rise” image and sought support for a “harmonious world” concept to reassure its smaller and weaker neighbors that China’s resurgence is not a threat to their economic and security interests, and that China has peaceful intentions for mutual growth and development. China acted on this new policy and successfully negotiated land border disputes with Vietnam, actively took part in ASEAN institutions, aided struggling economies during the 2007 and 2009 financial crisis, and it also partially lifted trade barriers for selective items to improve harmony and growth with its neighbors. On the other hand, on many occasions, China also diplomatically protested unilateral action by its neighbors in the South China Sea without engaging in any large military actions, but the skirmishes between China and other claimants have been consistent. Over the past several years, China’s foreign policy has become more aggressive and has undone decade’s worth of good neighborly diplomacy in Asia by declaring the South China Sea a “core interest” of Chinese territory and power. China’s assertive diplomacy is a consequence of growing Chinese military power and high running nationalism that, due to the financial crisis, underestimates other global powers.

Conclusion

From this analysis we see that a threat of regional instability over the South China Sea is overstated, because China’s aggressive diplomacy in relation to the South China Sea territorial dispute is always complemented by China’s emphasis on peaceful relations with its neighbors and attempts to resolve territorial disputes peacefully. This may seem like a paradox, but hardly so. China needs to secure control over the resources located in the South China Sea while also maintaining security in the area if the state is to enjoy the benefits of uninterrupted economic growth. This means that China needs to walk a fine line in order to maintain peace, but also to secure resources. It is extremely unlikely that it will abandon either of these goals by becoming either extremely cooperative or extremely aggressive. But this does not mean that China will continue to test the boundaries of either trajectory in an attempt to “know” its political surroundings. In the past, China successfully resolved many territorial disputes with its neighbors, including Vietnam, and it is a country overall more likely to compromise on territorial disputes. China and ASEAN signed a declaration on the conduct of parties in South China Sea, which advocates a peaceful resolution and strides away from the use of force. China has also shown that it maintains a position of openness to further dialogue for dispute resolution, and reaffirms that it will adhere to the South China Sea “code of conduct.” China’s focus on economic growth and increased trade with ASEAN rejects the possibility of the use of force. However, because China is engaged in a “balancing act,” we cannot dismiss the possibility of a limited military conflict between China and ASEAN because of miscalculations. It is also possible that due to a high domestic level of nationalism, China, Vietnam, and the Philippines can use this issue to divert attention from domestic problems, if the need arises.