It would be difficult to think of another country which has experienced such a roller-coaster of highs and lows in recent years as Brazil.

Just six years ago, this emerging-markets darling was posting 7.5% GDP growth, a robust bond market, and trusted political stability. But for the past two years, Brazil’s graduation party has been put on pause.

The economy has contacted by almost four points last year and will do so again this year, while deficits have swelled to more than 10% of GDP. Last year’s downgrade to junk bond status has Brazil borrowing at an asphyxiating 14% interest rate, making recovery very difficult. The overall loss of confidence relates to the massive, sprawling political corruption scandal known as lava jato (Operation Car Wash), which has ensnared some of the richest and most powerful Brazilian leaders across party lines.

Now, with the Summer Olympic Games less than 100 days away, the impending impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff has prompted a bit of an Ibovespa rally, as markets apparently see the prospect of a speedy “Dilmexit” as the best solution to the crisis.

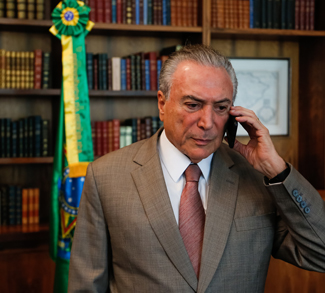

This optimism is misplaced. Investors would be wise to manage their expectations with regard to impeachment, and remember that this contentious process is not part of the anti-corruption campaign, as has been suggested by some media coverage. There are few signs that a provisional government under Vice President Michel Temer has the capacity or influence necessary to navigate the legislative paralysis in Brasília to pass reforms, while the economic policies of the Partido do Movimento Democrático Brasileiro (PMDB) appear to shift with the wind.

Not a Coup

Dilma’s supporters both at home and abroad have further added to the confusion by provocatively insisting that the impeachment is a “coup,” placing the crisis under an ideological lens in which “the elites” are conspiring to “overthrow” a popularly elected leader.

This is also a deeply misleading claim. The impeachment may be unfair (based on an unconvincing technicality), politically motivated (taking place within the legislature, it is a political, not judicial, process), and even arguably immoral (the lawmakers judging Dilma have far more serious corruption cases), but one thing it is not is illegal. The opposition has followed the letter of the law in the proceedings, and the sufficient threshold for grounds for impeachment is based on a vote – not a trial before a judge.

These two conflicting images of Brazil’s impeachment process – that it is either the culmination of an anti-corruption drive or that it is a putsch – serve to obscure the true origins of the economic crisis, and make it more difficult for the country to learn from past mistakes and unite behind a proper recovery effort.

These tensions were highlighted in a recent op-ed by Brazilian political scientist Luiz Eduardo Soares, who rejects the “coup” claims, but warns of a generalized myopia among those expecting impeachment to deliver a satisfying result. Despite Brazil’s pervasive corruption across seemingly every area of public life, Soares notes that many have subscribed to “the false idea that, by removing the PT government, Brazil will be free of the commingling between crime and politics.”

An Unsatisfying Process

The reason why impeachment isn’t going to work magic is that Brazil’s problems are more structural than political. The country finds itself in negative growth due to years of counter-cyclical macroeconomic policy aimed at softening the blow from the 2008 financial crisis, which entailed racking up unsustainable levels of public debt. Much of Brazil’s government spending is constitutionally mandated – representing one of the most intransigent and inflexible burdens on the economy – and this is a key reform that the PT has put off for years and years.

To date there has been no evidence directly linking Dilma to the Operation Car Wash scandal, but on the other hand, her best defense would be to argue incompetence, as she served as chair on Petrobras from 2003-2010 when all these alleged crimes took place.

The opposition PMDB, on the other hand, can hardly portray themselves as the defenders of the public interest. Prominent members were caught up in the PT’s Mensalão vote-buying scandal way back in 2005, while their deep involvement in the current corruption scandal has significantly eroded public trust (Dilma may only have about 10% approval ratings right now, but only 8% of Brazilians say they want a Temer presidency).

The next three in the presidential line of succession, Temer, house speaker Eduardo Cunha, and senate president Renan Calheiros, are all facing multiple corruption allegations. Upon assuming the presidency, Temer is liable to face the same impeachment proceedings as Dilma, since he signed off on the very same budgetary manipulations that serve as the basis for her removal. Cunha, who is currently being tried in the Supreme Court for corruption and money laundering, would likely barred by the courts from the presidency, and then Calheiros could yet again face impeachment.

A Test of Institutional Strength

Despite this vacuum of leadership, 61% of Brazilians still want to see Dilma impeached, and 58% already support impeachment of Temer, and he hasn’t even taken office. It may not be a process that delivers justice or governance, but there are a number of Brazilians I’ve spoken with who are simply eager to move things forward and get past this frustrating and damaging stalemate.

While it’s unlikely that Dilma’s impeachment would immediately calm the instability in Brasília, there are other reasons for mid-term and long-term optimism for Brazil. The country’s institutions are undergoing the most intense stress test possible, and for now, are holding firm. The problems we are seeing actually would remain invisible if Brazil lacked independent institutions, and these may be the sort of growing pains that should be expected of an emerging middle-income democracy. Alejandro Werner of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently described Brazil’s resilience in the face of these dual crises as “amazing,” and I tend to agree.

Investors may find Brazil’s current political atmosphere stifling and its corruption distasteful, but there’s a reason why foreign direct investment has risen to $17bn in the first quarter from $13.1bn in the same period last year – people are still betting on Brazil’s institutions and its people, even if the leadership class is in urgent need of renovation.

Brazil’s future may be uncertain, but it seems unlikely that it will look like the past, which is a step in the right direction.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.