Summary

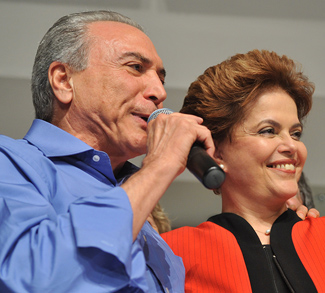

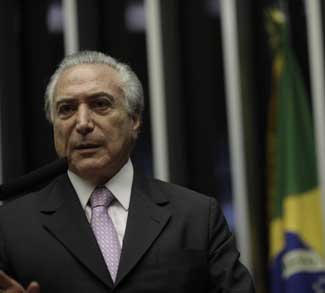

Brazil’s economy has shown signs of a modest recovery in recent months after its worst recession on record. President Michel Temer has passed pro-business reforms in hopes of attracting foreign investment and inspiring confidence in Brazil’s future. Temer also wants to cap government spending and make social security more restrictive. These are both ambitious proposals that require constitutional change; however, they are not without opposition. Although President Temer’s reforms have not received much international media attention in light of the Lavo Jato [Car Wash] scandal and the second round of corruption charges, they could radically change the way Brazil does business in the world economy.

Background

Here is a brief introduction to some of the reform initiatives being pushed by the Temer administration:

- Labor Reform. The most significant measures recently passed allow agreements to be directly negotiated between employers and workers, overriding the current labor law. The already-approved first part of the labor reform includes details on outsourcing, which makes it easier to hire temporary workers, even for extended periods. However, perhaps the most misunderstood and contentious aspect of the proposal was the regularization of the extended workweek. The proposal brings the maximum workday to 12 hours, but overtime is then limited to four extra hours per week, extending the hourly workweek from 44 hours to a possible 48 hours. Many Brazilians thought that a 12-hour workday would become the new norm. However, according to Claudinor Barbiero, a Brazilian expert in social security law, “… employees could work less, because there will be a limit for the weekly journey.”

- Pension Reform. Rising public debt is in large part blamed for Brazil’s economic crisis, and pension adjustment is one area in which the government believes it can make substantial fiscal headway. One of the most important points of the proposed reform is to have the private and the public sector follow the same rules. The current system appears largely unfair in that it allows some people to retire in their early 50s, and some public sector workers are entitled to earn their salary level upon retirement for the rest of their lives. The second point is that the government intends to establish a minimum retirement age of 65 for men and 62 for women.

- Energy Sector Reform. Earlier this year, President Temer announced a decree that nearly doubled taxes on fuel in an effort to reduce the government deficit. Meanwhile it appears that Petrobras, the state-run oil company implicated in the Car Wash scandal, is no longer required to have a substantial stake in projects, thus, shifting costs to fuel distributing companies. New bidding rules also appear to have reduced the obligation of local content requirements. It seems that changes are also on the way regarding electricity, as the government promised a new presidential decree in October.

- Foreign Trade. Brazilian companies are favored by the government over foreign companies. With high tariffs, Brazil remains relatively closed off to global trade. Without international competition, Brazilian products can be both overpriced and of subpar quality. Isolated by trade deals, Brazil became increasingly reliant on China. However, in 2014, China shifted focus toward a domestic-consumption economy. Thus, oil and agricultural exports suffered considerable downturns in Brazil. In addition, the discovery of large oil reserves off the coast of Brazil saw the country rely increasingly on oil exports until the collapse of oil prices in 2014. More recently, it appears that Brazil is taking steps to open its economy. In June 2016, the country asked to join the Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) negotiations. This month the government even took steps to join discussions regarding the Agreement on Government Procurement in the World Trade Organization (WTO). In May 2017, Brazil also began a process to become a member of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).