Summary

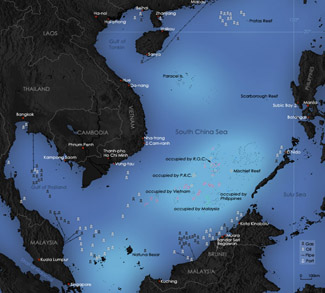

Last month saw the Trump administration publish its National Security Doctrine, within which China and Russia are identified as US rivals and “revisionist powers” whose rise has opened a new era of global competition as well as collaboration between great power poles. Evidence of a changing balance of power between the United States and other countries can also be found in a report by the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative of Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies, which revealed that in the South China Sea, Beijing has continued to defy international law by installing facilities such as high-frequency radar which can be used for military purposes on its man-made islands. China’s maritime activities reveal an emerging power that is committed to rolling back American influence in the western Pacific, and this conflict is now undermining the strategic framework that has emerged to regulate and protect the postwar global maritime commons. In turn, the United States is working closely with Japan, Australia, and India as part of ‘Japan’s Democratic Security Diamond’ (DSD). Collectively known as ‘the Quad,’ the four countries have just emphasized their joint commitment to safeguarding the maritime commons stretching from the Indian Ocean to the western Pacific.

Background

Law of the Sea? The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is the relevant international agreement that sets the rules through which states may interact in maritime matters such as navigational rights, sea mineral rights, and coastal waters jurisdiction. China ratified UNCLOS in 1996, though the U.S. has not (which weakens its position on China’s South Sea actions). China’s territorial claims and its island-building program meant to reinforce them have been found in violation of its UNCLOS treaty obligations in the judgment of the Permanent Court of Arbitration. China’s growing economic and military clout have so far allowed it to buy off or ignore objections from the U.S. and other Asian states however. With the U.S. not a party to UNCLOS and China flouting the agreement, the strategic framework for regulating the oceans could be in danger of becoming a dead letter.

![U.S. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo participates in the ASEAN Regional Forum Ministerial in Bangkok, Thailand, on August 2, 2019. [State Department Photo by Ron Przysucha/ Public Domain], cc Flickr U.S. Department of State, modified, http://www.usa.gov/copyright.shtml U.S. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo participates in the ASEAN Regional Forum Ministerial in Bangkok, Thailand, on August 2, 2019. [State Department Photo by Ron Przysucha/ Public Domain], cc Flickr U.S. Department of State, modified, http://www.usa.gov/copyright.shtml](https://dev.geopoliticalmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/ASEAN2019-768x369.jpg)