Summary

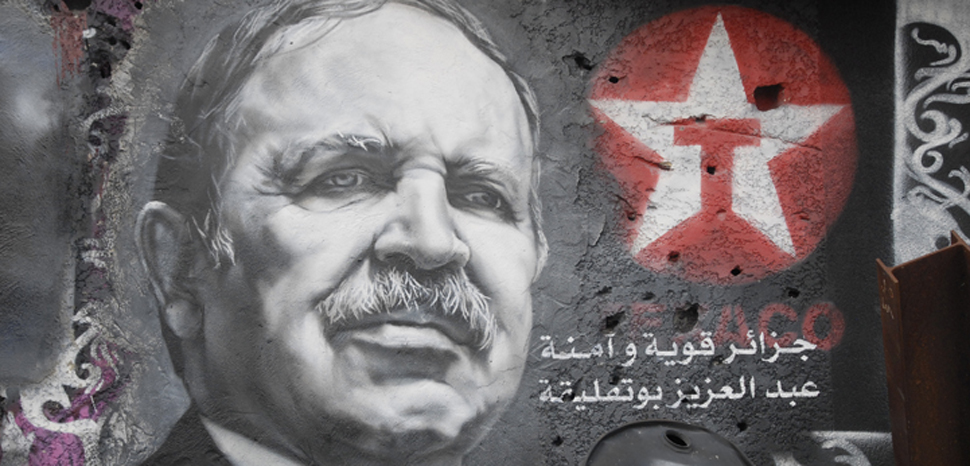

Algerians were originally scheduled to head to the polls on April 18 to pick a new leader. And it had been assumed that, for lack of any credible alternative, they would end up with an old one: The 82-year-old President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who has ruled the northern African country for 20 years.

But that was before the protests broke out.

After nearly a month of countrywide demonstrations, Bouteflika has finally blinked, announcing that he will not stand for a fifth term as president. He also delayed elections for a year, giving the ruling authorities a chance to reconsolidate under the new normal. Protesters received the news with a mix of caution and elation, and many are vowing to stay the course until free and fair elections are held.

Powerful insiders within ‘the pouvoir’ (the ‘powers-that-be) that sits atop of Algeria’s tightly controlled democracy may have initially allowed these protests in a calculated play against the ailing Bouteflika. However, history has shown that mass mobilizations can quickly take on a life of their own. And in the case of Algeria, they could bring sweeping domestic changes that resonate in the MENA region and across the Mediterranean in Europe.

Background

Large protests have been raging in various Algerian cities since President Abdelaziz Bouteflika officially confirmed his intention to seek a fifth term in the upcoming presidential election in February.

Earlier this week, more than 1,000 judges declared that they would refuse to oversee the polls if Bouteflika contests them. Elsewhere, clerics were openly defying instructions from the ministry of religion to cast the current regime in as favorable a light as possible and avoid messages of support to the protestors.

Then on Monday, Bouteflika suddenly relented and declared that he won’t be seeking a fifth term. In a letter to the Algerian people, the president outlined a plan to delay elections and remain in power until the end of 2019, at which time a new constitution will be drafted by an ‘inclusive and independent conference.’ The draft constitution will then be vetted in a national referendum.

There have been two main drivers behind the protests. One is the state of the Algerian economy. Youth unemployment is hovering at around 28%, and the country’s energy-dependent economy grew by just 0.8% in 2018.

Economic problems are underscored by Algeria’s daunting demographic outlook: the population has nearly quadrupled from 11.6 million in 1962 to 41.3 million now, with nearly half of the current population under 30 years old.

Put simply, the Algerian economy is under immense strain to provide new jobs for millions of people entering the workforce every year. So far it has failed to do so and there’s no immediate relief in sight in the form of either higher energy prices or a significant reform package from the government.

The second impetus driving protests is the state of President Bouteflika’s health. Frail, hunched over, wheelchair-bound, and all but absent from the public eye, Bouteflika has become a Wizard of Oz-type figure for many Algerians, with speculation rife as to whom within the pouvoir is actually controlling the country through the president. Bouteflika hasn’t even given a speech since 2013, and is said to have completely lost his voice following a stroke.

Impact

There’s a long list of potential consequences from the ongoing political instability in Algeria.

First it should be noted that the movement seems to have reached a critical mass where the protesters won’t go quietly into the night. We will either see major concessions from the establishment, namely a significant opening up of the political system, or we’ll see a gradual intensification of the current instability.

What happens next is anyone’s guess. Algeria has long been ruled by an opaque clique of elites existing at the nexus of political and economic power – ‘le pouvoir.’ This clique includes family members, advisors, and longtime allies of Bouteflika, along with key players in the security establishment. Those ruling from behind the president are a mystery, as are those who are apparently undermining him by allowing the protests to go unchallenged in the early days. But what’s clear is that there’s a schism in Algeria’s elite, and these differences could lead to fracturing and increased competition against the backdrop of a continued mass mobilization. The result could be powerful figures aligning with or against the protesters, all with an eye on securing a favorable position in the post-Bouteflika reality, whatever it turns out to be.

Given recent history, these political conflicts risk taking on an existential quality. Algeria descended into civil war once before following the annulment of an election victory by an Islamist coalition in 1991 – the first such free and fair election since the country’s independence. The war lasted over ten years and resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths.

The Bouteflika era may have been economically stagnant and a quintessential example of the resource curse in action, but it did represent an extended period of uninterrupted stability for one of North Africa’s most important states.

A breakdown in social cohesion and/or extended political crisis would involve considerable geopolitical fallout.

It would resonate on energy markets and particularly in the European Union, the largest buyer of Algerian oil. Algeria’s energy industry is already undercapitalized and in need of investment; political instability would further accentuate the problem by driving investors away and delaying much-needed reforms. Should the crisis trigger a resumption of civil war, there’s the potential for serious supply disruptions and price shocks on the global level. Oil currently accounts for around 85% of Algeria’s exports, so any disruption in the industry will ripple through the wider economy.

Algeria is also a key cog in regional mechanisms in the fight against cross-border terrorism. The country has its own experience with fighting an Islamist insurgency, as many returning fighters from the mujahedeen traveled to Algeria to fight in the civil war during the 1990s. The vast, mountainous expanse of Algeria’s southern desert regions are home to al-Qaeda-aligned terrorist groups that move seamlessly across the borders of Mali (home to its own simmering Islamist insurgency), Algeria, and Niger. Just two weeks ago, the French government confirmed that it had killed Djamel Okacha, a top commander in Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in Timbuktu. AQIM, which operates in southern Algeria, is responsible for several high-profile terrorist attacks, including an attack on a Sonelgaz gas plant near Algiers in 2009.

The threat is compounded by the prospect of ISIS fighters returning from Syria and establishing themselves in Algeria’s lawless south. A breakdown of central government authority would be a double-edged sword: it could derail crucial de-radicalization programs (which have been quite successful), and pull military assets away from the frontier.

Finally, there are potential consequences for migrant flows toward the EU. As the case of Libya shows, a breakdown in political order means border patrols and customs standards disappear, resulting in unbridled migrant flows across the Mediterranean. Given the outward migration pressures in countries south of Algeria, namely Mali and Niger, we could expect a substantial uptick in EU-bound migration in the event of a severe crisis (which, of course, would also produce a large outflow from Algeria itself).