The recent border clash between the two nuclear powers along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) has left India with 20 killed soldiers and, according to India’s minister for roads and transport, 40 Chinese casualties. Although the sides have reached an agreement to deescalate the situation following the deadly fight, the accord’s details remain unknown. Furthermore, both New Delhi and Beijing have deployed troops and military vehicles to reinforce their respective positions with no signs of timely withdrawals. In fact, India has admitted to having matched Beijing’s troop concentration along the Himalayan border.

While several reports cite India’s construction of strategic roads as triggers for the skirmish near Ladakh and Aksai Chin, the clash should be viewed through a greater geopolitical lens, one that accounts for the changing character of Sino-Indian relations and India’s renewed modus operandi.

It appears that India is gradually abandoning the Panipat syndrome and is willing to defend its strategic interests in a prompt and decisive manner. Coined by the late Jasjit Singh, an Indian military strategist, the syndrome alludes to New Delhi’s long tradition of chronic indecisiveness, sluggish response to security threats, and its inability to soberly assess the global strategic environment. In short, New Delhi only acts when the adversary is either on its doorsteps or when Indian policymakers are left with diminished options.

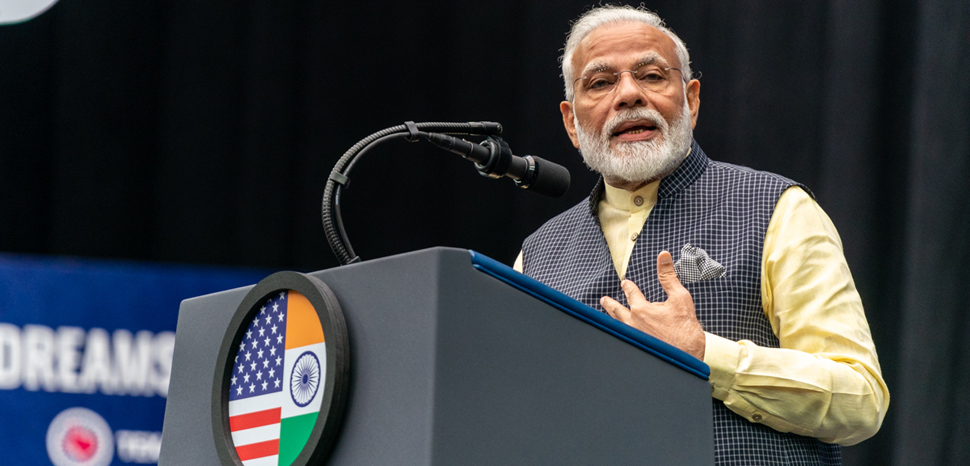

That said, to fully grasp the current impasse in Sino-Indian relations and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s assertiveness, a brief examination of India’s post-Cold War engagement with China will suffice.

In the waning days of the Soviet Union, India concluded that Moscow’s security umbrella could not be taken for granted. The changing geopolitical order required a new strategic rationale that would stabilize New Delhi’s relations with Beijing. Hence India’s continued rapprochements with China, which were best manifested in attempts to temporarily freeze the border dispute in the hope of establishing a collegial bilateral relationship. Despite initial progress in the form of shunning military options to resolve lingering disagreements and the organization of periodic high-level state visits, this early diplomatic success proved to be short-lived.

The inherent distrust persisted, leading to India’s nuclear tests in 1998 as a counter to both Pakistan and China. Additionally, Beijing upped the ante by questioning India’s sovereignty over Arunachal Pradesh in 2009. Furthermore, Indian intelligence was adamant that China continued to amass troops near the volatile state of Jammu and Kashmir.

It seemed only natural that these failed rapprochements, coupled with the meteoric growth of Chinese military power, would create a solid ground for Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to make a national comeback.

Upon assuming the premiership, Modi brought a new geopolitical pragmatism into his foreign policy conduct. For instance, after his election, many predicted that the relations with Washington would sour due to America’s refusal to issue him a visa as required by religious freedom legislation (Modi has been accused of having a hand in the 2002 religious pogroms in Gujarat). Nevertheless, once a prime minister, he chose not to dwell on Washington’s previous diplomatic rejection and actively engaged with the Obama administration for security reasons.

A vehement adherent to BJP’s assertive foreign policy ideology, Modi has demonstrated that he will not hesitate to utilize the military to balance against the Sino-Pakistani nexus. After all, he suspended Kashmir’s statehood, authorized the Balakot airstrikes reportedly eliminating a militant-run camp, and accelerated arms purchases both from Washington and Moscow.

More broadly, Modi has elevated India’s relationship with Japan to a strategic level, as evidenced by their joint critical infrastructure construction, India’s backing of Tokyo’s East China Sea claims, and enhancing military and technological cooperation. New Delhi also continues to actively work with Washington in the maritime domain, which includes complex naval exercises and intelligence-sharing. Once reluctant to engage with Australia strategically, Modi has recently signed two military pacts with Canberra as a direct result of Beijing’s military swaggering amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

He has done this without any chest-thumping and has refused to explicitly side with one bloc at the expense of another. For instance, while India has significantly pivoted to the United States to balance China, it has not undermined the Moscow option. Instead, Modi’s subtle realpolitik has cast a wide net around the world as India adjusts to China’s rise.

It is undeniable that the nations in the Indo-Pacific region have come to view New Delhi as a major strategic player able to take an action. However, it remains to be seen whether the inept Indian bureaucracy will catch up with Modi’s activist foreign policy and whether his successors will dial back India’s regional engagement.

As for the United States, there’s a growing consensus that India is poised to be a key partner in the new cold war with Beijing given the aligning strategic interests and the overall bilateral progress made in the past decade. And while American strategists should remain hopeful that China’s behavior will accelerate the demise of the Panipat syndrome, it’d be a grave mistake to assume that Washington has India in its pocket already.