Over the second half of 2020, Vietnam should focus on integrating the informal economy with the formal economy and resuming negotiations for a code of conduct in the South China Sea.

2020 was slated to be a big diplomatic year for Vietnam, as it holds the rotating ASEAN Chair. This is significant as it allows Vietnam to raise its diplomatic status within ASEAN and raise issues representing its national and regional priorities. Yet the COVID-19 pandemic derailed Vietnam’s diplomatic ambitions as states within the region had to focus on their respective pandemic responses. Critically, travel restrictions made it impossible to hold summits and engage in informal diplomacy, a key characteristic of ASEAN. Nevertheless, Vietnam is one of the few countries that has managed to bring the pandemic under control, at least for the time being. Despite having dense concentrations of population in its urban areas, a modest national budget, limited testing capacity, and a shared border with China, Vietnam has punched above its weight by relying on early prevention, robust contact-tracing, and transparent and effective governance. As of July 2020, Vietnam has around 400 cases and no recorded deaths. Vietnam’s containment success at home also sets itself up as a model for pandemic response and commands respect from other countries.

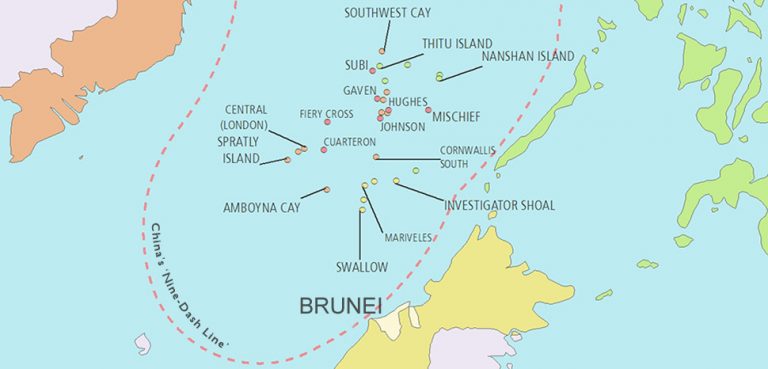

Notwithstanding setbacks in organizing conferences and summits due to travel restrictions, Vietnam has managed to lead ASEAN effectively. To illustrate, it chaired a series of virtual teleconferences discussing pandemic response, not only among ASEAN countries but also with other external partners like China, Japan, South Korea and the U.S. To further bolster its leadership role in ASEAN, Vietnam also engaged in “mask diplomacy,” donating face masks and other medical supplies to ASEAN countries like Laos and Cambodia, as well as the EU and the U.S. But the strongest display of Vietnam’s chairmanship of ASEAN came with the 36th ASEAN Summit. The regional grouping, known for its consensus-based decision-making and preference for informal, non-binding diplomacy, made a surprising move by affirming the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea as the legal framework to determine maritime claims and conduct maritime activities in the South China Sea. ASEAN’s unexpected pushback against China’s territorial and maritime claims can be contributed to Vietnam’s efforts to mobilize a united regional stance on the dispute. The question moving forward is whether that affirmation will be fractured by China’s longtime practice of obstructing and interfering in ASEAN consensus making on issues sensitive to Beijing such as the SCS.

Nevertheless, Vietnam’s effective pandemic response also comes with a heavy economic price. Its economy, one of the fastest-growing in the region, has been hit hard by the pandemic-induced recession. According to the Vietnam Institute for Economic and Policy Research, Vietnam registered GDP growth of 0.36 percent in the second quarter of 2020, a sharp drop compared to the last year’s figure of 6.71 percent. Other indicators do not present an optimistic trajectory for the economy either. For example, the number of temporarily suspended businesses increased by a whopping 38.2 percent year-on-year, and the number of registered laborers decreased by 21.8 percent. Two sectors that were severely impacted are tourism and manufacturing due to global travel restrictions and supply chain disruptions. That said, Vietnam remains a bright spot for economic recovery, being one of few countries with positive growth in the first half of 2020 thanks to its successful early handling of the pandemic.

A more assertive China in the South China Sea represents a second headache for Vietnam. The global pandemic has not been able to slow China’s efforts to push its territorial and maritime claims as it continues to harass and prevent other claimants, including Vietnam, from conducting maritime activities. For example, a Vietnamese fishing ship was reportedly rammed and sunk by a Chinese maritime surveillance vessel in April. Vietnam also had to cancel contracts with two international oil companies, possibly due to pressures from China. Amid escalating tensions with the U.S., China will continue to robustly assert its claims in the South China Sea, risking more tensions with Vietnam. At the same time, stalled negotiations on a code of conduct (COC) due to travel restrictions will complicate Vietnam’s leadership in ASEAN. As virtual negotiations are not an option, as they would nullify one of ASEAN’s enduring strengths of informal, non-binding consensus making through dialogue with its members. Vietnam will need to find a way to hold negotiations and prevent China from watering down this critical document.

The first half of 2020 has brought both tangible achievements and challenges for Vietnam. In the second half of the year, Vietnam will need to continue its effective leadership in ASEAN by speeding up economic recovery and pushing for face-to-face COC negotiations. A recovered economy not only bolsters Vietnam’s diplomatic status but also frees up its attention and resources to focus on regional issues. This will necessarily need to include the informal economy which was asymmetrically negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, the slow and bumpy recovery in the United States and Europe might delay Vietnam’s own recovery as these are two critical trading partners of Vietnam. At the same time, since other ASEAN countries are also struggling with the same issue, Vietnam could leverage economic recovery into a shared goal for regional cooperation and put forward ideas to accelerate recovery. One particular proposal to lessen the economic hardship could be integrating the informal economy. The pandemic has highlighted the plight of migrant laborers working in the informal sector of ASEAN economies; some of them boast very high informal employment rates. Pandemic-induced economic recession and a lack of social security benefits could threaten their livelihoods, even pushing them back into poverty. Vietnam could advocate for proposals to integrate the informal sector into the formal economy, such as providing training and improving access to finance and working conditions. Integration not only helps informal workers secure a better future for themselves but also allows ASEAN countries to improve their competitiveness in a digitized economy and prevent social unrest.

Here, Vietnam should actively work with extra-regional partners to strengthen integration, bolster local health care capabilities, and provide economic lifelines to those in the informal economy to help them weather the COVID-19 induced economic storm.

The approach should not be a zero-sum equation. Using the rubric of non-traditional security, Vietnam needs to find ways where both Japan and China can deploy their collective capabilities to stabilize the ASEAN economy, mitigate the spread of COVID-19, and enhance intra-ASEAN integration. Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific Vision (FOIP) and China’s BRI are useful platforms that do have overlap in some of their raison d’être and synergies in their capacities and capabilities. It is critical that Vietnam canvasses ASEAN member to voice their needs such that they can collectively convey them to extra-regional partners to stabilize the region.

More difficult but equally important are holding face-to-face negotiations for a COC, which should be the second focus for Vietnam. Because virtual conferences are not a good fit for ASEAN’s discreet and informal diplomacy, easing travel restrictions for officials attending negotiations might be a good start. Moreover, while ASEAN’s recent statement on the South China Sea dispute is a step in the right direction, it is not enough. Vietnam should leverage its position as the current ASEAN Chair to expand cooperation with other powers that share the same concerns about China’s ambitions in the South China Sea. The strongest US statement to-date on the disputes, which rejects China’s entire claim and aligns U.S. positions with the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration’s ruling, could be an encouragement for Vietnam and other claimants to mobilize a united ASEAN stance during negotiations.

All in all, Vietnam has achieved striking accomplishments despite the COVID-19 black swan event. Even though remaining issues continue to complicate Vietnam’s efforts, Vietnam could still hope for a better second half of the year by using its position to accelerate intra and extra-regional cooperation to foster economic growth, stability, and sustainability while at the same time contributing to managing security challenges facing ASEAN.

![U.S. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo participates in the ASEAN Regional Forum Ministerial in Bangkok, Thailand, on August 2, 2019. [State Department Photo by Ron Przysucha/ Public Domain], cc Flickr U.S. Department of State, modified, http://www.usa.gov/copyright.shtml U.S. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo participates in the ASEAN Regional Forum Ministerial in Bangkok, Thailand, on August 2, 2019. [State Department Photo by Ron Przysucha/ Public Domain], cc Flickr U.S. Department of State, modified, http://www.usa.gov/copyright.shtml](https://dev.geopoliticalmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/ASEAN2019.jpg)