Summary

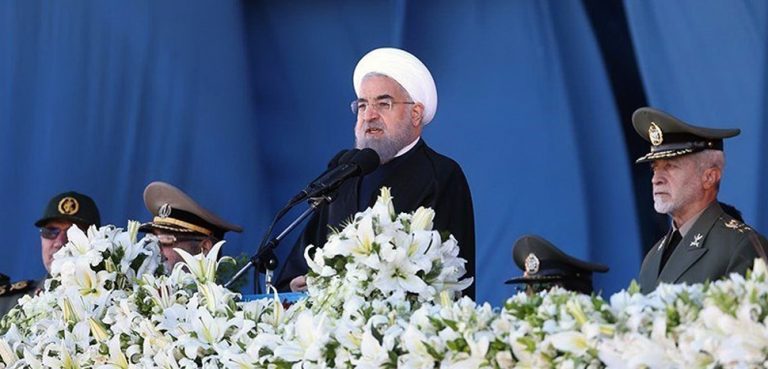

Wedged between protests in Tehran and the ramping up of a new US-led sanction regime, the administration of Hassan Rouhani finds itself between a rock and a hard place.

Iran’s economic situation was already bleak before President Trump decided to pull out of the deal and re-impose sanctions. Now the national currency – the rial – is in free-fall, crashing through a series of historic lows against the US dollar. The outlook will only be deteriorating from here on out as buyers reduce their orders of Iranian oil ahead of November 4. That’s the date when countries must reduce their Iranian purchases to ‘zero,’ according to recent statements from US officials. Further compounding the regime’s misery is the sizable demonstration that has broken out in Tehran, a city that has hitherto been an island of calm amid the churning sea of economic grievances throughout the country.

Impact

A currency in free-fall. The rial is now in free-fall, imperiling the government’s current account and placing a host of consumer goods outside the budget of middle class Iranians. At the end of 2017, one US dollar purchased 42,800 rial; on the eve of President Trump’s withdrawal from the nuclear deal, it was 65,000 rial; as of June 27, it was as high as 90,000 rial. Of course these are the black market rates. The government’s official peg of 42,000 continues to go ignored and unheeded as Iranians desperately shift their assets into US dollars to escape from spiraling inflation.

An important takeaway reflected in the downward trajectory of the rial is that the economic promise of the Iran nuclear deal was still unrealized even before President Trump formally pulled out of it. Iran was already teetering on the brink of recession in May; President Trump merely provided the shove.

One positive for the Rouhani administration is the country’s solid hard currency reserves and trade surplus going into the current crisis. The IMF estimated in March that the government held some $112 billion worth of foreign reserves and that it was running a comfortable current account surplus.

Now the government will shift into crisis management mode, attempting to limit the drain on its foreign reserves for as long as it remains the target of US sanctions. The Rouhani administration has introduced some hastily-assembled reforms meant to stem capital flight, including the banning of some 1,300 consumer items deemed non-essential. So far these efforts have fallen short and the black market exchange rate continues to yawn.

Strikes in Tehran. Shopkeepers in Tehran’s sprawling Grand Bazaar have been on strike for the past few days. The strike began with mobile phone sellers, who have been hit particularly hard by the rial’s plunge. They were then joined by thousands of protestors demonstrating against rising prices and the government’s failed economic policies. The size of the gathering was enough to prompt the authorities to shut down the metro to curb its further expansion. And though the Tehran demonstration was eventually dispersed by riot police, similar protests and acts of solidarity were recorded in the cities of Arak, Shiraz, Tabriz, and Kermanshah.

Any demonstration in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar is particularly sensitive given its role in the Islamic Revolution that brought the current regime to power in 1979. In fact, unrest in Tehran is a relatively new development. When protests swept the country last December and January, reaching some 80 towns and cities and eventually resulting in 25 deaths – Tehran remained quiet. Much like the protests currently taking place, the December protests decried worsening living standards and water shortages.

Trump maintains a hard line on Iran oil exports. When the EU broke with Washington and declared that it would try to keep the Iran nuclear deal in force, its ability to actually do so was contingent on two variables: 1) whether or not the U.S. would grant EU companies waivers, allowing them to continue trading with Iran without being locked out of the US financial system; and 2) whether or not the EU could quickly assemble a united front both within and without to endure US pressure. So far neither has played out in the EU’s favor, which suggests that November 4 will bring a considerable shock to Iran’s oil-dependent economy as European companies join the race to the exits.

This week, a State Department official said that no waivers would be forthcoming and that all companies would need to stop doing business with Iran’s energy industry by November 4.

Buyers in Japan and Taiwan have already begun to plan for a drawing down of their purchases of Iranian oil.

The looming question is what Iran’s biggest purchasers – India and China – will do. The Indian government has maintained that it only recognizes UN sanctions, not unilateral US sanctions. However, in the absence of waivers from the U.S., Indian companies may find it difficult to do business with Iran. Securing willing middlemen for insurance and shipping purposes is made extremely difficult by the presence of US sanctions. There’s also the matter of paying for the oil; USD is off the table since the transaction can’t clear in the US financial system. It’s likely that the rupee-rial payment mechanism of 2010-2014 will be revived sometime in the near future.

China is another top buyer of Iranian oil, importing around 650,000 barrels a day on average from Iran over the first part of 2018, equivalent to roughly a quarter of Iran’s exports. China is less reliant on the US financial system than India, and could choose to continue or even increase its purchases of Iranian crude after November 4. We know that Iranian officials unsuccessfully tried to secure guarantees from the Chinese side that oil purchases would continue regardless of US actions. It’s possible, albeit unlikely, that China’s purchases are being treated as a negotiating chip in the wider US-China trade talks (or war) that are currently unfolding.

Forecast

Iran has an elevated short-term risk outlook: the economy has been sliding for over a year, it’s about to get worse when oil revenues are impacted by sanctions, and the population is losing patience with the government. Strikes, protests, and even a repeat of the sort of nation-wide movement witnessed in 2009 are all distinct possibilities. Should a repeat of 2009 come to pass it could be expected to be a bloody affair as the ruling authorities and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps would not give up power without a fight.

In terms of new sanctions, it remains to be seen how much of Iran’s current export capacity will be taken off the market. The EU, China, and India may talk a tough game, but their final orders will be dictated by the ground-level realities of circumventing the US financial system, in addition to wider oil market considerations, mainly whether or not OPEC and Russia can absorb market without causing upward price shocks. It’s not just Iranian exports that need to be compensated for, but Libyan and Venezuelan ones as well, as the oil industries of both countries are in a seemingly terminal decline.

At the height of the last sanction regime, around 1.2 million barrels of Iranian crude were removed from the market every day, with the remainder being covered by waivers meant to insulate buyers from supply shocks (mainly India and China). As of May, Iran is exporting 2.7 million barrels per day.