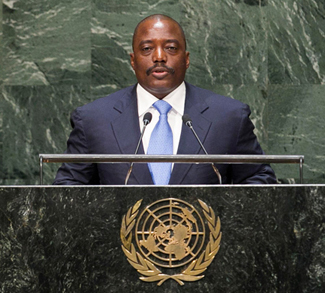

Back in January, the capital of Kinshasa and other cities were rocked by widespread protests when Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) President Joseph Kabila’s regime tried to pass a law requiring a national census to be held before future elections. The opposition reacted furiously, accusing the president, who has been in power since 2001, of seeking to prolong his term in office. Eventually the census proposal was dropped and the government backed off, announcing that presidential elections would be held in November 2016. That clock is now ticking, and there are few indications the government is seriously preparing for a post-Kabila future. On the contrary, events in neighboring Burundi may be encouraging some people around the president to think again.

As electoral norms spread through sub-Saharan Africa in the 1990s, a number of strongmen emerged who rigged elections to keep themselves in power indefinitely. Term limits were introduced into the constitutions of countries like Burundi or the Congo precisely to prevent the emergence of such an electoral dictatorship. Alas from Russia to Turkey to eastern Africa, in the twenty-first century elected autocrats have learned to manipulate constitutions and exploit weak judicial systems to their advantage. Now the apparent success of Burundi’s Pierre Nkurunziza in side-stepping constitutional term limits in Burundi shows how the spirit of the law can still be evaded if a legal pretext can be patched together by the party in power.

The politics of Burundi, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo have all been tragically tied together by conflict and instability spreading from one to the other, so Burundi’s example does not auger well for its fragile neighbours’ future stability and good governance. President Nkurunziza’s claim that his first term in office should not be counted because he had not been elected has a certain plausibility but was grossly irresponsible in a fragile and ethnically divided polity. At the first sign of a serious backlash a statesman would have dropped his bid and allowed a caretaker government to oversee a proper election. Instead, after stacking the constitutional court with his supporters, Nkurunziza is accused of pressuring it to rule in his favor so he could stand for a third term behind a façade of judicial approval.

He had to ride out violent opposition protests and a coup attempt that together cost dozens of lives, but he has managed to secure himself an extra few years in power.

Few people believe the Burundian president’s claims to respect legal and constitutional restraints on his power and prerogatives. In an unprecedented rebuff, Nkurunziza’s re-election was not even observed by the African Union. Alas, in the bear-pits of his neighbors’ politics many leaders will be keen to follow his recent example. For example, there are no doubts that the fourteen year-old regime of Joseph Kabila next door is any less devious in protecting its monopoly on executive power. With the right court rulings and parliamentary maneuvering, the DRC’s own term limit issue could be circumvented. Mr Kabila could swap chair whilst remaining in power simply by stripping the presidency of its powers whilst increasing those of another power center such as the prime minister’s office. As the reaction on the streets of Kinshasa in January showed however, there are few signs it could be done without bloodshed.

Sadly the present Kinshasa regime has precious little democratic traditions to restrain its maneuverings. The current president inherited his position from his father when the latter was assassinated. The presidential incumbent before that was another Joseph, the infamous Mobutu, who looted the DRC for thirty years and murdered or exiled any political opposition. Four years prior to the present drama in Burundi, the DRC’s 2011 election results had already brought opposition accusations that the Congo’s Supreme Court had not examined electoral results thoroughly enough when it awarded the victory to the incumbent Kabila administration. How much truth there is in this matters less than the fact that many in the Congolese opposition are likely to believe the judiciary is biased against them. If the DRC’s Court became an actor in any kind of constitutional crisis in the run up to next year’s elections it would not be seen as a neutral institution but as a tool of the ruling Kinshasa clique.

In the African Great Lakes region contests for power within states are always nerve-wracking moments for their neighbors because of the ease with which instability in one can spread to the others. The Second Congo War is a prime example of this transmission of instability from one part of the Great Lakes region through porous borders to another. The conflict was triggered in aftermath of the Rwandan genocide when ‘Hutu power’ extremists fled from their country into eastern Congo following their defeat at the hands of Tutsi forces. Since the eastern DRC was home to previous waves of Hutu and Tutsi refugees from both Burundi and Rwanda and their descendants, the Rwandan Hutu militias swiftly added to eastern Congo’s own swirling bush wars, and brought their genocidal ideology with them. A much wider war was sparked when Kinshasa prevaricated and seemed unable or unwilling to control the situation in the east. Rwanda and Uganda promptly invaded and placed Joseph Kabila’s father Laurent in power, trigging a region-wide struggle involving nine African states. Millions died across the DRC and peace has only sporadically returned since then.

The weakness of the DRC to armed incursions from its neighbors is reason to be concerned when those states start to look fragile themselves. The peace between the DRC, Rwanda, and Burundi remains extremely brittle. In the east of the Congo the remnants of the Rwandan Hutu militias, local Mai-Mai militants, and assorted other armed groups still pose a threat to civilians, if not to Kinshasa. Meanwhile in May, as tensions in Burundi escalated, the Rwandan government seemed to be preparing the diplomatic ground for an armed intervention if ethnic killings broke out there. Fortunately the Burundi situation has been resolved for now without escalating into inter-ethnic fighting, both because President Nkurunziza’s re-election bid was opposed by many members of his own Hutu ethnic group, and because he successfully seems to have bought off some of the opposition, splitting it politically.

Much money, time, and energy has been spent by the international community in Burundi, Rwanda, and the DRC trying to prevent a return to the tidal wave of blood that soaked all three countries between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s. That may all be at risk if the Kabila regime takes a leaf from President Nkurunziza’s book. Repeated rebellions against Kinshasa, some of them backed from neighboring Rwanda and Uganda, have rocked the DRC since the end of the Second Congo War, which ran from 1997 to about 2003. It is a testament both to the weakness of the Congo’s central government and the susceptibility of the DRC’s east to its neighbors that the embers of Rwandan-linked revolts were not fully stamped out until 2013, and that the Kabila regime needed repeated international intercessions to do so.

It is therefore difficult to see how Kinshasa can extended Joseph Kabila’s term of office as neatly as Pierre Nkurunziza has in Burundi. The DRC is a much larger country than its neighbors and there are simply too many armed groups beyond the control of the security forces. Meanwhile the army itself is divided and weak, full of former rebel fighters and widely distrusted for its corruption and brutality. Any bid by Kinshasa to stay in power using a legalistic fig-leaf would almost certainly trigger a new revolt in the east and possibility other parts of the DRC and if Kabila’s actions were to spark another uprising against his regime it is debatable if the West would intervene to save him.

However it would also be difficult for neighboring governments in Burundi, Uganda and Rwanda to overlook the security and financial incentives of meddling in the DRC’s factional politics. If one country starts to back an armed movement, the others will follow suit, threatening a return to regional instability. Despite the dangers, the temptation for Kabila to stay on somehow will be strong, as will the pressure on him from members of his inner circle. The DRC’s best hope is that President Kabila has learned from his father and his namesake’s mistakes and does not try to outstay his welcome as President Nkurunziza has done in Burundi. Peace in the Great Lakes region could soon depend on the Congo not following in its neighbor’s footsteps.