Summary

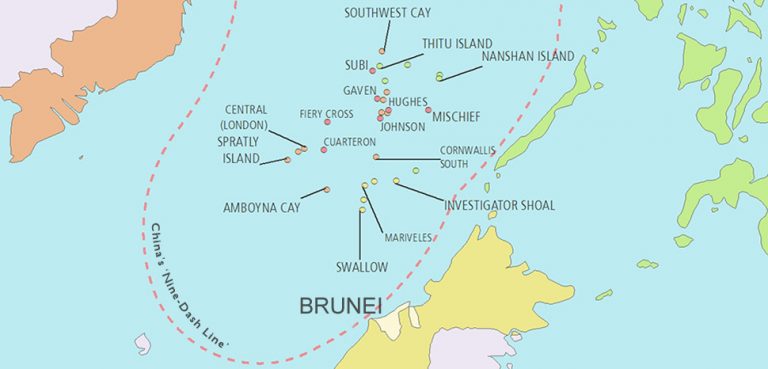

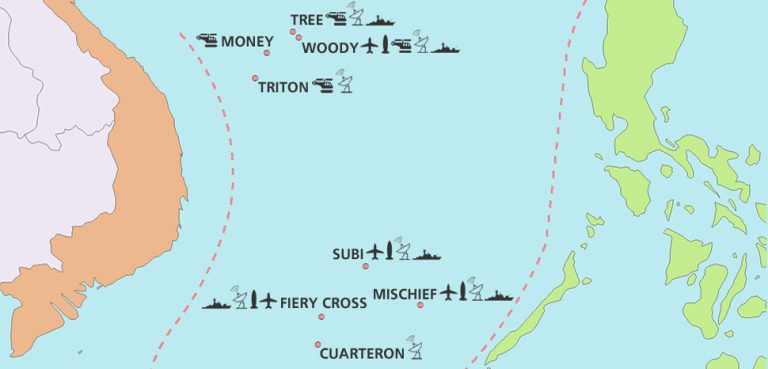

China and its neighboring countries have advanced overlapping claims to the South China Sea, an area rich in oil and gas reserves and a key shipping lane through which trillions of dollars of global trade flow. As China’s economic ascent facilitates Beijing’s military expansion, other regional players—including members of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN)— have also experienced a surge in nationalism and military capabilities. Yet China’s increasing assertiveness and its island-building in disputed waters are issues that are often shelved during ASEAN meetings. Moreover, with China’s newly proposed code of conduct, it would appear that ASEAN will remain on the sidelines, with Beijing continuing to steer future dialogue on the South China Sea dispute.

The code of conduct is a set of rules outlining the norms, responsibilities, and practices for players in the South China Sea. It seeks to prevent clashes over energy reserves, fishing, land reclamation, and military conflict in the contested waters. The latest framework for a code of conduct, endorsed by ASEAN on August 5, advances the 2002 Declaration of Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea. However, the new draft’s non-legally binding and non-enforceable nature has raised doubts over the impact it will actually have in terms of resolving territorial disputes.

A final version of the negotiating framework leaked to the media in May claims the code of conduct should not be considered an “instrument to settle territorial disputes,” but instead a tool to “promote maritime cooperation in the South China Sea.” Negotiations for an actual code of conduct have taken 15 years. Meanwhile, details have not yet been released about the framework’s content. While some are hailing the new code as progress on the South China Sea dispute, others view it as a tactic for China’s slow consolidation of maritime power at the expense of its fractured opposition.

This leaves several unanswered questions: What does the ASEAN-China draft framework on a code of conduct actually mean? And to what extent will it matter for the South China Sea dispute? Although a combination of internal and external factors has precipitated this seemingly positive development, ASEAN states are still left hoping that a ‘spirit of cooperation’ can succeed where international law has failed.

Background

An Elusive ASEAN Consensus on the South China Sea

The Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) is a regional grouping that aims to foster economic, political and security cooperation among its ten members. Founded in 1967, ASEAN’s raison d’être is to facilitate the region’s state-building process by creating a regional environment conducive to development. Shared external threats and domestic political imperatives (i.e. regional hostilities and communist-led insurgencies) influenced the design of the regional organization. Hence, ASEAN’s founding documents heavily emphasized the importance of respect for sovereignty, non-interference, and peaceful conflict resolution.