Summary

Most of the international community celebrated the nuclear deal between Iran and the countries of the so-called “5 + 1” group. Only Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the new president of the United States, Donald Trump, did not. The agreement signed by the permanent members of the UN Security Council (France, China, United Kingdom, United States and Russia) plus Germany (hence 5+1) imposes limitations on Iran’ uranium enrichment program. In exchange, Iran received an easing of economic and trade sanctions. It also repatriated some $150 billion of its own money that American banks froze as part of the punitive measures the United States imposed on Iran after the 1979 Revolution and the related hostage crisis. The Iran nuclear deal is not especially ambitious, but it is significant. As a direct result of it, several countries have restored official and trade relations with Iran, including the United States. Not for nothing, Boeing has reached a deal to sell about $ 27 billion worth of aircraft to Iran Air. But Trump has put this agreement into question, souring the bilateral tone to levels not seen since the time Ayatollah Khomeini was Supreme Leader. In fact, Iran has replaced Obama’s Russia as the main geopolitical foe for the Trump administration.

But if there is a widely misunderstood country in the Middle East, it would be Iran. So, it would be useful, in fact necessary, to review the country’s recent history to better understand the present geopolitical stakes.

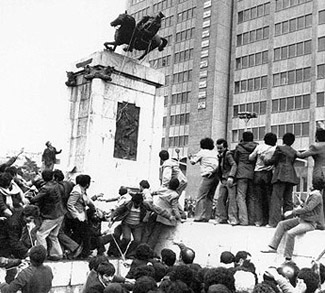

Iran is a complex country that defies easy generalization. The most important thing to keep in mind is that Iran has deep contradictions. It is an Islamic Republic, who’s legal and political system are inspired by Sharia law, yet it also boasts one of the most secular elites of any Middle Eastern country. It has endured deep sanctions, yet it has managed to develop a far more diverse economy than any of its Persian Gulf oil-producing neighbors. Most, importantly, unlike the Arab countries of the Middle East that the British and French midwifed from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire, such as Syria or Iraq, Iran has kept virtually the same borders for the past two thousand years. Its recent history is ‘unique’ in the Middle Eastern context. Iran has experienced rapid and deep changes in the past four decades. In 1979, Iran became an Islamic Republic, one of only four in the world – the other three being Afghanistan, Mauritania and Pakistan. But, Iran is the only Shiite one, which is remarkable in itself; it is also one of the keys to understanding its regional ambitions and the nature of much of the recent tensions with Saudi Arabia. Iran didn’t evolve into a Shiite Islamic Republic. It got there by way of revolution; indeed, a revolution that for the 20th century was second only to Russia’s in impact. The Iranian Revolution of 1978-1979 smashed the Shah and his monarchy. It also sent the existing international order into disarray. Up until 1979, the Shah’s Iran was the biggest US ally in the Middle East. The Revolution changed everything. It is the key to understanding Iran today and what challenges lie ahead, particularly in view of what the Trump White House intends to do.

The official religion of the Islamic Republic of Iran is, of course, Islam; although other religions are allowed (Christianity, Judaism, Baha’ism and Zoroastrianism). Yet, it’s crucial to note that a significant proportion of Iranians do not practice any religion, especially in Tehran and large cities. In the case of women it becomes more evident because young women in particular find ways to avoid the Islamic “dress code.” It’s much different than the case in Saudi Arabia, where the morality police strictly enforce the segregation of men and women, as well as other restrictions. Women in Iran wear the veil loosely, showing a large part of their hair, almost as if it were a tall scarf; they like to paint their nails, put on makeup, and dress no differently than women would in Toronto or New York in their private lives.

In other words, Iran runs at two speeds. And although the political sphere may be dominated by adaptations of religious principles, there are ever fewer graduates at the religious learning centers, the madrasas, of Qom, which dominated the Majles (assembly) in the early years of the Revolution.