Summary

US-Vietnam relations have reached new heights amidst China’s rise to both regional and global prominence. China’s growing hegemony and ambitions in the South China Sea have not only alerted its neighbors in the Asia-Pacific, but also US foreign policymakers concerned with reassuring its five mutual defense alliances in the area. While The U.S. has been strategically hedging under Obama’s “Asia Pivot,” South East Asian countries are playing a hedging game of their own.

Hedging is an approach that combines hard and soft power measures to resolve contentious issues vis-à-vis different levels of ‘engagement’, ‘binding,’ and ‘balancing’. Historically, the U.S. has relied on the Philippines and Thailand to safeguard its interests in the region. However, its partnership with these two regimes has been strained in recent times, given high levels of internal volatility and authoritarian tendencies. President Rodrigo Duterte has shown a cautious pivot towards Beijing in recurring statements that downgrade U.S. ties. Meanwhile, Thailand’s military junta is viewed as an unreliable security partner.

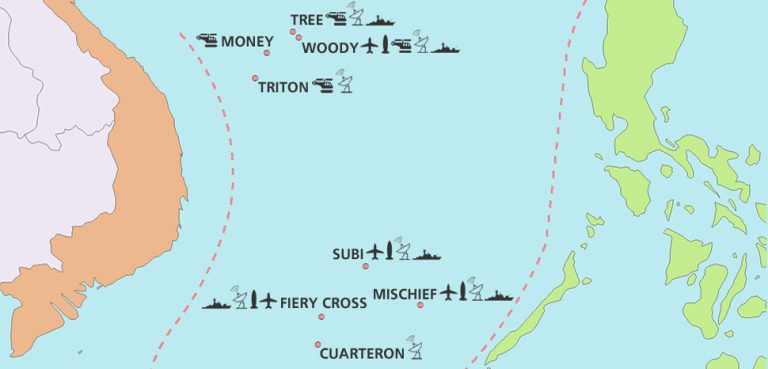

As a result, the U.S. has sought to diversify its hubs-and-spokes alliance system in the region by accelerating security cooperation with Vietnam to counterbalance China’s increasing assertiveness. Obama’s visit to Hanoi following the 20th anniversary of normalized diplomatic relations celebrated the two countries’ “comprehensive partnership,” an overarching framework established in 2013 that seeks to advance US-Vietnam bilateral relations in political, economic and social spheres. Three central issues of concern include Vietnam’s intensifying rivalry with China over contested waters, stalling economic growth, and the communist regime’s human rights record.

The most substantive achievement so far has been the United States’ agreement to lift its four-decade-long lethal arms embargo on Vietnam. In effect, Washington has recruited Hanoi as its new strategic partner by enabling it to upgrade and diversify its military imports from Russia, while enhancing its maritime defenses against China. Other deliverables include $18 million in new assistance to propping up Vietnam’s maritime capacity, VietJet’s $11.3 billion deal with Boeing, General Electric’s $94 million wind energy project with Cong Ly Company, the State-Department funded Fulbright Economics Teaching Program, not to mention, visa entry changes aimed at facilitating short-term business and travel links.

This signifies not just a “marriage of convenience,” but a move beyond the last remaining vestiges of the Cold War and toward a new chapter in US-Vietnam relations. Public opinion polls show that the Vietnamese view the U.S. in a much more favourable light than China. That being said, this progress should not be taken for granted, as it has required great time and effort before the two countries could even fathom seeing eye-to-eye against these new Pacific currents. The process of rapprochement can thus be understood in a three phase progression that culminated in the “comprehensive partnership,” which has once again been called into question with the ascension of the Trump administration.