The momentous decision taken in 2017 by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Bahrain to sever all ties with Qatar sent shock waves through the whole world. The so-called “Boycott Quartet” justified its drastic move by singling out Qatar as the primary source of instability in the already volatile Arabian Peninsula. While numerous countries from the Middle East to Africa scrambled to take sides and curry favor with either Qatar or the Quartet, the row represented an ill-timed nuisance for Tunisia.

Indeed, in 2017, Tunisia was still in the throes of a delicate diplomatic effort aimed at weaning itself away from Qatar. Undoubtedly, as a result of the 2011 revolution, Tunisia’s relationship with Doha blossomed into a full-fledged friendship. Al Jazeera, the notorious Qatar-funded news outlet, applauded the 2010-2011 protests against secular President Ben Ali and immediately welcomed the subsequent electoral success of the Islamist Party Ennahda. In contrast, the advent of political Islam drove Saudi Arabia and the Emirates away from Tunis.

Even though Doha’s financial backing provided an indispensable respite, Tunisia realized that it couldn’t solely rely on Qatar to tackle the intractable economic issues produced by the 2011 turmoil. Therefore, Tunisia strove to attract investment from both Abu Dhabi and Riyadh, while preserving its friendship with Doha. Just as this diplomatic gambit seemed to pay off, the Gulf crisis broke out. In light of the détente that it was painstakingly cultivating with the UAE and Saudi Arabia, Tunisia could not afford to openly side with Qatar in the Gulf row. Therefore, Tunis reasoned that neutrality represented the best course of action.

Eventually, Tunisia’s neutrality didn’t pan out as it hoped. Saudi Arabia partially accepted to play along but, from July 2017 on, Tunisia-UAE relations deteriorated to the point where the North African country found itself at square one, i.e. hanging on to Doha’s support to get by.

The ascent of Ennahda: Tunisia flirts with Qatar and Turkey

Cracking down on Islamism and striving to preserve Tunisia’s secular identity had been the two elements that best characterized Ben Ali’s rule since he assumed power in 1987. While succeeding in preventing Islamism from creeping into Tunisia’s political and social life, Ben Ali’s repressive approach toward the movement fueled the resentment of many and eventually backfired. It is no wonder, then, that both moderate and radical Islamist organizations played a crucial role in precipitating the collapse of Ben Ali’s regime. In 2011, therefore, Islamism was poised to fill the vacuum that the implosion of the Democratic Constitutional Rally (Ben Ali’s party and instrument of power) was to produce in the Tunisian political scene.

In effect, this vacuum was promptly filled by Ennahda, a political party constituted in the 1980s, originally inspired by the Iranian revolution and the Muslim Brotherhood. Ennahda went on to win the 2011 elections by a landslide and form a government that immediately provided a shot in the arm to Tunisia’s cooperation with Qatar. This is not surprising. Indeed, Been Ali’s systematic suppression of Islamism in Tunisia was frowned upon in Doha which, in turn, has a history of supporting political Islam, and specifically the Muslim Brotherhood. Therefore, Qatar’s main media outlets reacted positively to the end of Ben Ali’s rule and the nascent synergy between Qatar and Tunisia was ready to take off.

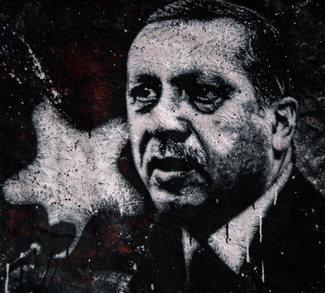

In addition to being historically influenced by the Muslim Brotherhood, Ennahda’s top brass have frequently held up Erdogan’s Turkey as a model for Tunisia. According to Ennahda’s founder Rachid Ghannouchi, Turkey demonstrates that modernity and Islamic values can perfectly coexist in the same polity. Inevitably, Ghannouchi’s eulogizing Ankara paved the way for increasingly stronger links between the incipient Ennahda-led government and Turkey. In September 2011, Ankara and Tunis signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, which was followed up by a series of meetings designed to buttress the collaboration between the two countries in a variety of fields.

Cementing ties with both Qatar and Turkey was the cornerstone of post-revolutionary Tunisia’s foreign policy. Such triangular diplomacy helped Tunisia navigate the economic and political fallout of the 2011 revolution. Moreover, the new-found synergy between Turkey, Tunisia, and Qatar didn’t look like any other marriage of convenience, i.e. it was not merely based on the economic calculations of the countries involved. Rather, it looked ultimately premised on values and, specifically, on a common Islamist foundation.

…But it comes at the cost of alienating Saudi Arabia and the UAE

Conversely, Saudi Arabia and the UAE followed the rise of Islamism in Tunisia with increasing apprehension. Significantly, by the time of the Tunisian revolution, both Gulf states were already wary of the Muslim Brotherhood, Ennahda’s original source of inspiration. Consequently, both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi signaled their malaise with Ghannouchi’s electoral success by steadily loosening their ties with post-revolutionary Tunisia. While the UAE took the drastic step of recalling its ambassador to Tunisia in 2013, Saudi Arabia granted Ben Ali and his family sanctuary in the Kingdom. While the Royal family quickly explained its move away, it is essential to provide historical context to the Kingdom’s decision in order to appreciate its significance for the future of Saudi Arabia-Tunisia relations.

In 1941, Saudi Arabia offered sanctuary to former Iraq Prime Minister Rashid Ali al-Gaylani, after its failed attempt to oust the British from Iraq with the assistance of the Axis. Back then, the Kingdom’s obstinate refusal to hand al-Gaylani over to the British seemed inconsistent with the Royal family’s long-standing cooperation with London. However, Saudi Arabia had an ulterior motive and the ousted Iraqi Prime Minister was tasked by Riyadh with furthering its agenda in the Middle East. Specifically, in 1958 al-Gaylani attempted to overthrow Iraq’s Prime Minister Abd al-Karim Qasim, detested by the Saudis due to his cozy relationship with the Iraqi Communist Party. Whether the are Saudis nurturing Ben Ali and his cohorts in the Kingdom to later threaten post-revolutionary Tunisia – especially if the North African country fails to bridle Islamism – is, of course, anyone’s guess but, in light of the al-Gaylani affair, the possibility cannot be ruled out.

The “Troika” steps down: mending fences with the UAE?

Following its landslide success in the 2011 elections, Ennahda formed a government with secular parties Ettakatol and Congress for the Republic. The new government – which earned the sobriquet “Troika” – did little to disprove those segments of the Tunisian population that feared that Ghannouchi’s party was bent on erasing Tunisia’s secularist identity. Ennahda succumbed to pressure from the secularists – who accused Ghannouchi’s party of permitting radical Islamism to rear its head in post-revolutionary Tunisia – and the infamous Troika crumbled. In 2014 elections, the secularist party Nidaa Tounes took over.

Nidaa Tounes’ electoral coup was hailed by the Saudis and the Emiratis as a breath of fresh air. In 2014, political Islam looked on the defensive in Tunisia and so too appeared Qatar’s clout in the country. The Saudis rushed to capitalize on this new political climate. In the context of “Tunisia 2020,” the international investment conference aimed at helping Tunisia overcome its protracted economic crisis and stay the course towards democratization, the Saudis pledged Tunis $780 million. Lest Riyadh steal its thunder, Qatar promised the North African country as much as $1.25 billion. Significantly, the Emiratis shunned the conference. Nevertheless, Abu Dhabi had no intention of giving up and went on exploring ways to bridge the chasm with Tunis.

The greatest opportunity to do so was offered by the Libyan imbroglio. With Ennahda at the helm, Tunisia moved steadily closer to the Qatar-supported Government of National Accord and, conversely, alienated the UAE-backed Haftar camp. This was clearly the by-product of Ennahda’s association with Qatar and reflected post-revolutionary Tunisia’s attempt to integrate into Doha’s web of diplomatic alliances. Nonetheless, Tunisia didn’t completely break off ties with Haftar and the reason for this is twofold:

Firstly, Tunisia borders Libya and, understandably, is highly interested in warding off further spillovers from the Libyan crisis – particularly in terms of terrorist activities – into its territory. Because Tunisia’s primary concern is stabilizing its eastern frontier and buttressing its national security, it is bound to negotiate with both the GNA and the Haftar camp in order to facilitate the emergence of a stable compromise between all the belligerents.

Secondly, following Nidaa Tounes’ taking the helm in 2014, Tunisia set upon preserving dialogue with Haftar as a conduit to mend fences with one of his principal backers, namely the Emirates. On its part, Abu Dhabi wanted Tunisia to decidedly support Haftar. Such a U-turn would have been, in the eyes of the Emiratis, evidence that Tunisia was genuinely interested in an accommodation with the UAE. Importantly, by siding with the Emirates on the Libyan crisis, Tunisia would have demonstrated to the Emirates that it is not completely subordinate to Doha, and that its economic partnership with Qatar didn’t restrict its diplomatic leeway.

This diplomatic endeavor seemed to bear fruit in 2017, when Haftar was officially invited to Tunisia. Haftar’s initial reluctance confirmed that, even after the ascent of secularist Nidaa Tounes, Tunisia was still particularly close to Qatar. Nevertheless, Haftar quickly backtracked and accepted to hold a meeting with Tunisian President Essebsi to discuss the feasibility of a concerted settlement of the Libyan crisis. Importantly, the “Libyan track” toward Tunisia-UAE rapprochement was supplemented by encouraging signs on the economic front. The UAE seemed ready to assist Tunisia in jump-starting its faltering economy, with the latter being now able to leverage its flirtation with the Emiratis to extract more financial support from Doha.

Qatar gloats as Tunisia and the UAE start at square one

The outbreak of the diplomatic crisis between Qatar and the “Boycott Quartet” nipped the emerging reconciliation in the bud. Its consolidated relationship with Doha notwithstanding, Tunisia refused to take sides, most likely not to scuttle the incipient détente with the UAE. Nevertheless, Tunisia further tightened its economic ties with Qatar in November 2017, a step that apparently didn’t go down well in Abu Dhabi. It is no coincidence that a diplomatic quarrel between the Gulf state and Tunisia unfolded over the following month, when the former decided to bar Tunisian women from boarding flights to the Emirates. In response, Tunisia pulled no punches. In an attempt to let the row peter out – and, most likely, acknowledging to have gone too far – Abu Dhabi clarified the rationale behind the ban by citing imminent security concerns. The explanation didn’t satisfy Tunisian Foreign Minister Khemaies Jhinaoui, who demanded a public apology from the Emirates.

In light of the ensuing downturn in Tunisia-UAE relations, there’s little doubt that the flight ban constituted a watershed event. The “Libyan track” – i.e. Tunisia’s attempt to improve ties with the Haftar camp as a vehicle for better relations with the Emiratis – has likely been put on the back burner by Tunisia, as its Foreign Minister Jhinaoui recently held a telephone conversation with his GNA’s counterpart Taher Siala to discuss “ways to strengthen bilateral relations and complementarity between the two sister countries.” As if it were not enough, in July 2018, Le Monde Afrique broke the story of the alleged coup d’état that now-former Tunisian Interior Minister Brahem was planning in collusion with the UAE intelligence services. Reportedly, the foiled plot was ultimately designed to drive Ennahda off the political scene and eradicate Islamism in Tunisia, thus bringing the country back to its pre-revolutionary situation. Irrespective of the veracity of this allegation, the outcry that the news immediately triggered in the country is telling in a number of respects.

Firstly, it demonstrates that post-revolutionary Tunisia’s polity is still highly volatile and prolonged internal instability – with the Tunisian public still so susceptible to rumors of either alleged or actual foreign interference – might prevent the country from pursuing its foreign policy objectives, i.e. pursue a truly neutral foreign policy by playing, if need be, both sides of the fence vis-à-vis the quarrels between Riyadh, Abu Dhabi and Doha. Considering how the Brahem affaire played out, either Qatar, the UAE, or Saudi Arabia may now derail one another’s schemes in Tunisia by disseminating rumors of reciprocal interference. The implication is that Tunis will not cease to be the battleground for the Gulf states’ opposing ambitions any time soon.

Furthermore, the protests against alleged UAE interference indicate that the 2011, 2013, 2016, and 2018 protests didn’t exhaust the resentment and dissatisfaction of large segments of the Tunisian populace. Whether for economic or political reasons, a significant number of Tunisians do not shy away from taking to the streets and raising their voice. Again, the Gulf states or any another influential actor might capitalize on the inflammable spirit of the Tunisian public to further their agenda in the country, by either instigating self-serving unrest or by steering the existing resentment toward their own objectives.

Right now, Doha is seemingly winning the battle for influence in Tunisia. Qatar is still the first Arab investor in Tunisia and it won’t be supplanted easily, especially if Tunis fails to come to terms with the Saudis and the Emiratis. However, Tunisia’s economic predicament and fragile political institutions will prevent Qatar from keeping Abu Dhabi and Riyadh at bay. For its part, Tunisia is aware of the necessity of looking for alternatives to Qatar’s support. At any time, Doha might pull the plug on investment and financial aid in order to compel Tunisia to openly align its foreign policy with Qatar’s. As the Gulf crisis shows no signs of abating, this might not be a remote prospect. Therefore, by showing that it has credible alternatives, Tunis might be able to obviate potential blackmail on the part of its current benefactor and, simultaneously, enlist Saudi Arabia’s and the Emirates’ financial backing to finally overcome post-revolutionary instability.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect the official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any other institution.