The tiny Islamic sultanate of Brunei has long been labelled the ‘silent claimant’ in the South China Sea, opting to lay low while other countries have taken a more confrontational approach toward pressing their territorial claims in the hotly contested region. China has long been viewed by the two foremost Southeast Asian claimant states, Vietnam and the Philippines, as the primary antagonizer due to its military posturing in the Spratly islands and the extensive land reclamation work it has carried out on remote outcrops in disputed waters – developments which have only further infuriated Hanoi and Manila.

In recent years, these two nations have attempted to take China to task, with Vietnam unleashing regular bouts of fiery rhetoric directed toward Beijing while the Philippines opted to take its case to an international tribunal, which ruled in its favour in July 2016 (though both have since opted for a more conciliatory posture). In contrast, Brunei has firmed up its understated approach, having grown increasingly reliant on China economically and politically following a succession of large investment deals and improved bilateral ties.

With Brunei now firmly brought on-side, Beijing’s charm offensive has succeeded in leaving ASEAN deeply divided on the South China Sea dispute.

Brunei’s claims and ASEAN discord on the South China Sea dispute

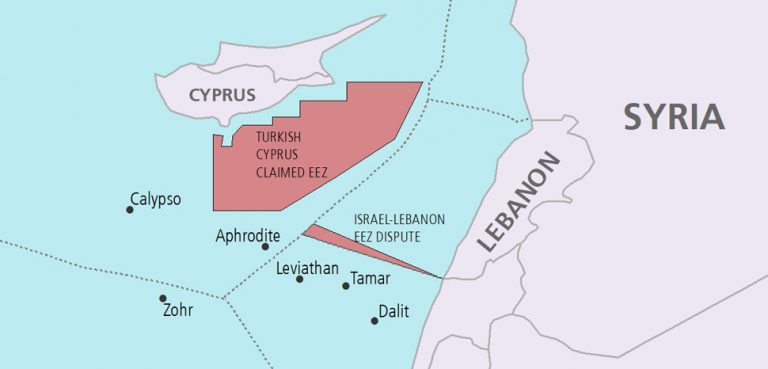

The South China Sea – as a vital regional maritime trading and shipping route, as well as being home to rich fishing grounds with vast sub-sea oil and gas reserves – has long been the site of intense competition in East Asia. China claims virtually the entire body of water as its own, and has pressed its historical claim to sovereignty via a contentious R.O.C map from 1947 that shows the sea encircled by a nine-dash line marking the extent of its self-declared territorial waters.

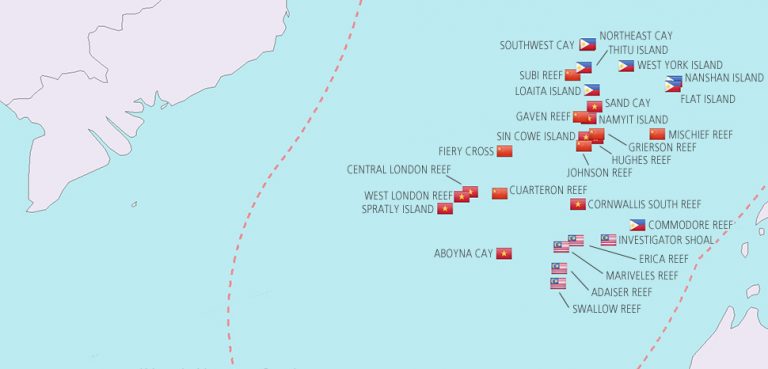

Beijing also claims ownership of two island groups within the sea: the Paracels in the northern portion and the Spratly archipelago to the south. However, Taiwan (as R.O.C), Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia also claim various stretches of water based on claims of historical ownership, control and usage of specific land features, and the modern legal regime represented by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The agreement came into force in 1982 and permits states an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extending 200 nautical miles from their coastline.

Brunei’s claim is relatively limited in comparison to the other five claimant states. Brunei claims only a 200-nautical mile EEZ under the terms of UNCLOS, in addition to several land features falling within its legally delimited boundaries in the southern portion of the sea, including Louisa Reef, Owen Shoal and Rifleman Bank. In direct contrast to each of the other claimants, Brunei does not occupy any land features in the sea and maintains no permanent military presence in the area to enforce its claim.

Since publishing a map in 1984, which was followed by an updated version in 1988 depicting the boundaries of its proposed EEZ, Brunei has remained largely silent on the issue, leaving its long-term strategy for pursuing its claim shrouded in uncertainty. In the intervening period, maritime tensions in the region have increased as other states have opted to pursue their claims more forcefully. China has launched an assertive campaign of militarization and construction activity to demonstrate its ownership, while Vietnam and the Philippines have toughened their own stances in response, only to eventually back down to varying degrees. On several occasions over the past two decades, naval stand-offs and diplomatic rows have ensued between the littoral states, whilst the U.S. has sailed warships through the area in controversial ‘freedom-of-navigation operations’ designed to demonstrate that the areas in question are still considered international waters. All the while, Brunei has looked on as if it were merely an outside observer.

As the disputes have heated-up, ASEAN has become increasingly divided on the issue. China initially sought to entrench divisions within the bloc through diplomatic means, pressuring several of the non-claimant ASEAN states – namely Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar – not to speak-out too forcefully on the issue. These three countries also happen to be Southeast Asia’s poorest and the most reliant on China economically, providing further imperative not to criticize Beijing’s South China Sea policy. Such pressure resulted in ASEAN failing to issue a joint communique after the Phnom Penh summit in 2012 for the first time in its 45-year history, over disagreement on how to approach the South China Sea dispute.

In recent years Beijing appears to have added Brunei – the smallest and arguably weakest claimant state – to the list of ASEAN nations potentially willing to display greater deference to China’s claims in the South China Sea. The apparent shift manifested in April 2016 when Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi announced that China had reached a four-point consensus with Brunei, Laos, and Cambodia on the South China Sea issue, agreeing the disputes were not an issue for ASEAN and should instead be resolved through ‘dialogues and consultations between the parties directly concerned.’ This agreement was seen as a coup for Beijing, which through engaging Brunei managed for the first time to bring a claimant state into line with its own long-held position that the disputes should not be resolved through multilateral forums but instead through bilateral talks between the states involved.

Economic reliance on China will ensure Brunei’s continued silence

Why has Brunei ignored calls for a unified ASEAN response and instead aligned itself more closely with China’s view on the South China Sea? Much of the answer comes down to economics. Brunei can no longer rely on its oil and gas reserves – the bedrock of its economy for decades – for sustained growth. The recent decline in global oil prices has hit government revenues hard, whilst Brunei’s domestic reserves are predicted to run out in the next few decades. The oil and gas sector has consistently accounted for more than 60% of Brunei’s GDP and over 95% of its exports.

This makes the natural resource industry vital for Brunei’s ruler, Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah, to retain the political legitimacy required to govern. As revenues dry up, the social contract between the state and its citizens will inevitably evolve, creating a need for economic diversification to secure not only continued prosperity, but also stability of governance in the sultanate. Brunei has already set in place an ambitious restructuring plan, dubbed Brunei Vision 2035, which aims for a dynamic and sustainable economy based on an educated and highly-skilled workforce, designed to enable the maintenance of high living standards in what is one of Asia’s wealthiest per-capita nations.

To achieve this vision, the Sultan has looked to encourage outside investment. China has emerged as Brunei’s dominant partner in this regard, with its combined investments in the country now totalling US$4.1 billion. Several major Chinese-funded infrastructure projects have gotten underway in recent years, with more projects planned further down the line. The most prominent is a large oil refinery and petrochemical complex currently under construction near the capital, Bandar Seri Begawan. The first phase of the project is expected to be completed by the end of the year, before a second phase costing US$12 billion will significantly expand the plant’s capacity in the coming years. Investment has also landed outside of the resource sector, with Chinese firms involved in the construction of ports and aquaculture projects along Brunei’s coastline in the north, providing a boost to the fishing industry. In 2014 the two nations also announced the creation of the Brunei-Guangxi Economic Corridor, in an attempt to boost trade between the sultanate and China’s southwestern coastal provinces. Officials said at the time that trade in sectors such as biotech, fisheries, and halal foods would be intensified.

In step with these financial arrangements and trading initiatives, bilateral relations have flourished. Recent years have seen an uptick in the number of high-level visits and formal meetings between the two countries’ leaders and senior officials, who have spoken of their shared desire to enhance people-to-people exchanges through forging closer cultural and educational ties and encouraging tourism. Chinese President Xi Jinping met Brunei’s Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah most recently in September, when he praised Brunei’s efforts in ‘strengthening China-ASEAN relations.’ Xi added that he hoped to align China’s Belt-and-Road Initiative with the development plans of Brunei and other ASEAN countries.

Political niceties aside, last year China overtook Malaysia and Singapore as Brunei’s primacy source of imported goods, with almost 25% of imports now coming from China. China is also rocketing up the list of Brunei’s major export destinations, and Chinese investment in the country is expected to increase further in the coming years. Given the increasingly central and influential role of China in Brunei’s shifting economy, and the dependency this inevitably creates, Brunei is now even less likely to risk upsetting China by looking to advance its South China Sea claims in the near future.

Brunei and China use the South China Sea dispute to secure mutual gains

The unspoken arrangement whereby Brunei remains silent on the South China Sea issue in order to secure Chinese investment has the potential to benefit both countries. Even if it was on a sound, self-sustained economic footing, as a small country Brunei was always going to have a difficult time enforcing its claim against a far more powerful China. Instead, Brunei opts to take a deliberately quiet approach, though one that falls short of relinquishing its claim entirely. The issue remains present in the background where it serves as leverage to secure Chinese investment to aid the country’s long-term development plan, which in turn is essential for maintaining the legitimacy of Brunei’s rulers.

Meanwhile, in courting Brunei economically and diplomatically, China has for the first time been able to persuade a claimant state to back its own long-held view that the disputes should not be settled through multilateral mechanisms, further entrenching divisions within ASEAN over the South China Sea. This bides China time to enhance its de-facto control over the contested waterways. Beijing also hopes to use Brunei as a positive example of the benefits that can arise from joint development and mutual co-operation in the maritime realm. China needs clear examples of such successes at a time when it is looking for its Belt-and-Road initiative to take-off. If Brunei noticeably benefits from Chinese investment, other states in the region may be lured into pursuing a similarly co-operative path in search of joint economic gain.