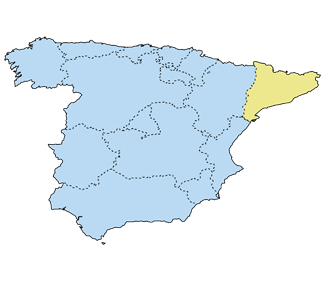

Emerging from a year rife with political, royal, and economic scandals, Spain has begun 2014 as Europe’s political tinderbox, providing the EU with the most potentially challenging secessionist movement in the Western world. Artur Mas, president of the Autonomous Region of Catalonia, has publicly called on leaders of the EU to pressure Spanish President Mariano Rajoy to allow a referendum on Catalonian independence, which the regional government in Barcelona has scheduled for November 9, 2014. President Rajoy, for his part, has stated categorically that the planned unconstitutional referendum is illegal, and that he is not in favor of altering the 1978 constitution to “satisfy someone who will not even then be satisfied.” On January 13, Rajoy assured President Obama that Spanish sovereign integrity is not up for negotiation, curtly dismissing the concern.

A brief analysis of the Catalan secessionist movement and the Spanish state’s reaction is crucial for forecasting 2014, as conflicts of this kind in Spain have had a historical tendency to include or affect other nations of Europe as well. As the EU is undergoing its most severe trial yet in coping with the destabilization caused by economic hardships in various member countries, the Spanish secessionist crisis is set to exacerbate the already tense debates occurring over nationalism, state sovereignty, and government authority in general. Spain is set to once again be an ideological staging ground, this time hosting the fight for the survival of the very concept of state sovereignty and integrity in the now universally democratic Europe. Whilst Spain has dealt with vigorous independence movements in Catalonia and the Basque Country in the recent past, most contentiously during the Second Republic (1931-1939) and the decades of ETA terrorism that plagued Franco’s tenure and the transition to democracy, the present conflict is playing out in the even more complicated arena of EU politics, testing the EU’s ability to deal with democratically processed sedition, and also testing a sovereign country’s legitimate right to maintain territorial integrity.

The Catalans are shrewdly highlighting that if democracy is the preeminent political virtue of Spain and the EU, then on what basis does the Spanish state deny self-rule to Catalonia, thereby continuing a policy deemed by Barcelona to be “authoritarian”? This very question is more than a rhetorical flourish. It strikes at the fundamental core of the ideological pillars of the Spanish state, as it questions whether the present democratic experiment is the political heir to Franco’s regency or to the ill-fated Second Republic. In most places perhaps this question would be mere pedantry; in Spain this is a controversy for which certain actors are willing to kill. The question is even more relevant considering that the Spanish state, since the presidency of Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo (1981-1982), has been more than anemic in its articulation of the principle of the inviolability of the national territory, equivocating more than pronouncing a firm and unalterable dedication to sovereignty. In essence, Madrid has recurrently employed appeasement of the separatists instead of dealing with the messy politics of principles disparaged by lukewarm pedagogy since 1976.

Right-wing pro-democracy movements like “Democracia Nacional” are channeling the widespread public discontent with the establishment socialist and conservative parties into demonstrations that challenge the central government’s tepidity and fan the flames of ire in the extremists. Right-wingers and separatists taunt each other into open street fights, both groups using incredibly inflammatory symbols: the right-wingers employing the Fascist salute, whilst the separatists wave pro-ETA flags in stadiums, inherently glorifying the murder of their unwanted fellow citizens.

The Anatomy of Catalan Secessionism: Old Wounds and New Platforms

Catalan secessionism is inseparable from memories of the Civil War and its aftermath, which directly incite Spaniards to every emotion conceivable. Catalonia received its autonomous-region status for the first time under the Second Republic (1931-1939), when secessionists merged with Anarchists, Communists, Socialists, and general republicans to fight their common enemy. With the victory of General Franco’s Nationalist forces in 1939, all regional autonomy was abolished. Suffice it to say, it is a political conflict fraught with a passionate zero-sum mentality.

Universal in the Catalans’ claims for meriting independence is an exclusionary argument for the historical, linguistic, cultural—and even racial—differences between Catalonia and the rest of Spain. When Catalan nationalism made its first dialectical appearance in the 1880s, it was invariably framed in the positivistic-eugenic theories prevalent at the time, as Pompeu Gener’s “teoria racial de la nacion catalana” (“racial theory of the Catalan nation”) of 1887 testifies. Furthermore, the theories were inherently anti-Semitic, as Catalan apologists claimed that Catalonians were “Arian-Gothic,” as opposed to the “semitic” Castilians—a clear reference to the historically large presence of Jews in Castilian lands. Racist arguments in favor of Catalan secession were prevalent until 1945, when world opinion would no longer legitimate that premise. Even today, strains of this kind of thought occasionally seep out, even from the highest-ranking Catalan regional leaders, especially when denigrating the Spanish region of Andalusia.

To the casual observer, it is very difficult to differentiate fact from propagandistic fiction. Another omnipresent contention of the Catalan secessionists is language. Although the Spanish Constitution of 1978 explicitly mandates all school children to use Spanish, public schools in Barcelona are notorious for treating Spanish as a second language alongside English, even going so far as only providing lessons in Spanish for two hours a week, and only after the children are nine years old. This was brought to the attention of the Supreme Court in 2012, which mandated that Spanish be the primary language of instruction, a ruling that Catalonia is not expected to implement, and has not at the writing of this article. The manner in which Catalan nationalists use their language is perhaps the most telling aspect of their enterprise to construct an identity for political purposes. According to statistics from both the Spanish government and the regional government in Catalonia, Spanish is, by far, the predominant language of Catalonia, both as a mother tongue and as a language of social interaction and commerce. Most importantly, it is estimated that only 34% of Catalonians identify Catalan as their mother tongue, and if one considers writing ability, the percentage never exceeds the 30+ percentile. In bookstores, 85% of titles are in Spanish, and demand for movie titles in Spanish is over 90%.

As the public outside of Spain usually only sees coverage of Catalonia’s mild requests that Madrid allow the non-binding referendum to take place, a veneer of respectability oftentimes hides the reality of the violent strands of the secessionist movement that plagues the streets of Barcelona. Pro-Spanish businesses that do not participate in the “human chains” or shows of force in favor of secession are many times attacked and boycotted, and any showing of the Spanish flag is brutally suppressed. Elements of the Catalan terrorist organization “Terra Lliure” are still active in the streets, although the organization was formally disbanded in 1991 and its leadership migrated into the far-left political party Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (Republican Left of Catalonia). Recently in September of 2013, a judge in Barcelona openly defied Madrid and warned that any law enforcement sent to interfere with Catalan secession would be met with force.

Catalan nationalism, like many nationalisms before it, is highly irredentist in its hegemonic aspirations. Catalan nationalists claim that a “pan-Catalonia” exists that does not only include the region of Catalonia, but also the Balearic Islands, the principality of Andorra, Valencia, the Rosellon region of Southern France, a part of Aragon, the town of Alguero in Sardinia, and the Murcian shire of El Carche. Valencia, in particular, is already voicing concerns about this imperialist posture of the Catalan nationalists.

Further Political Complications

There is widespread speculation that the increased nationalistic fervor on the part of Catalan nationalists is being fanned by the political elites in Barcelona in order to pressure Madrid into capitulating more national tax revenue to the province. Over a year ago when Artur Mas requested it from the Spanish President, he was refused, and soon after began the increased agitation. Furthermore, Catalonia has been financially bailed out for two years in a row, and the central government has not exercised its legitimate right to reign-in regions that continually run a deficit, as Catalonia does (Barcelona has been running a deficit of over 2 billion euros a year). Tax revenue is another chief advertising tool of the secessionists, and Catalonia now stays with 60% of the taxes collected in its territories, as opposed to the economically stronger region of Madrid, which stays with a mere 17% of its collected taxes. The regions that yield the highest income to the state are Navarre, the Balearic Islands, and Madrid—and the regions that receive the least in help are the Balearic Islands, Madrid, and La Rioja. Artur Mas has maintained five Catalan embassies in major cities, and has announced the creation of a new one in Washington, D.C., despite already having one in New York City. To further aggravate Madrid’s frustration, Catalan police make 40% more than the National Police, and 50% more than the Guardia Civil (militarized police), the Catalan civil service is paid more than the Spanish civil service, and even the regional Catalan president is paid more than the national president.

On the issue of EU membership, Artur Mas has admitted that in the case of secession, Catalonia would be excluded from the EU, and any future accession would have to get past Spain’s veto power. In raw terms, this would mean a drastic devaluation of the Catalans’ money if they also leave the Euro.

Concretely, the Catalans’ request that Madrid allows a non-binding referendum to take place on November 9 is constitutionally beyond the power of the president to grant. The vast majority of legal experts are convinced that there is no constitutional framework, under the current constitution, that allows any sort of secessionist referendum to occur. Those opposing Catalan secession also understand that there really is no such thing as a “non-binding referendum on independence,” as the political capital a “yes” result would give the separatists might very well be too much for a tepid central government to oppose.