The C5+1 format, a platform for dialogue and cooperation between the five Central Asian nations and the U.S., could gain new momentum after a series of high profile meetings in less than a year. However, how far this initiative can go will depend on the continuous involvement and interest of the parties involved, particularly Washington.

C5+1 Today

The first C5+1 meeting took place in Samarkand in November 2015, and the second occurred in Washington in August 2016. The most recent one was held in New York in September 2017 when, according to the U.S. State Department, then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and the foreign affairs ministers of the Central Asian states discussed greater cooperation under said format, as well as “ways to promote Afghanistan’s economic development within a regional framework.”

The State Department notes five projects that C5+1 focuses on: counter-terrorism under the auspices of the U.S. Institute of Peace; “facilitating private sector development of the internal Central Asian market”; promoting “low emission and advanced energy solutions”; and analyzing environmental risks under the umbrella of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

Apart from the 2017 C5+1 meeting, other noteworthy initiatives include meetings between US President Donald Trump and President Nursultan Nazarbayev of Kazakhstan in January 2018, and with President Shavkat Mirziyoyev of Uzbekistan in May 2018.

Central Asia: (Un)united?

One Central Asian expert summarized the future of this initiative to the author very bluntly: “C5+1 only works if the U.S. is involved, otherwise it does not.” The argument being that Central Asian governments, in spite of their statements that preach regional integration and cooperation, still have little interest in working as a united bloc (a high level March 2018 conference in Astana notwithstanding). Even more, without U.S. funding, the aforementioned projects would be doomed to failure due to lack of interest.

With that said, it is worth noting that Kazakhstan has taken a prominent role in approaching extra-regional partners, while Uzbek President Mirziyoyev is keen on leaving behind the isolationism of the Islam Karimov regime. The one glaring exception is Turkmenistan, as President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow seems content in following his predecessor’s isolationist foreign policy, and also to perpetuate himself in power. Thus, a general lack of cohesion should not be interpreted as continuous isolationism.

In spite of some promising recent developments, there is no certainty that greater regional integration experiments will come to fruition. One Central Asian expert was optimistic, hinting at greater open borders between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, and the recent suggestion by a Kazakh senator to establish a single Central Asian visa to promote regional tourism and attract extra-regional visitors as examples that greater integration, and even the creation of the Central Asian Union, are possible. On the other hand, another Central Asian expert argued that C5+1 and other regional gatherings are just opportunities for photo shoots and mutual praising, and there is no sincere intention to establish a common foreign policy.

C5+1 vis-a-vis Russia and China

The C5+1 is Washington’s main tool to approach Central Asia as a region. The other one is the US-Central Asia Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) Council. During their May meeting, President Trump made an offer to President Mirziyoyev to host said meetings. “If it works, TIFA would be a good way to promote U.S. trade with Central Asia… it will never reach Russian or Chinese numbers, but it’s something,” a Washington insider explained. Finally, there have certainly been important bilateral initiatives, like President Trump’s recent meetings with the leaders of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, but even these are too sporadic to cement strong bilateral ties.

Alarmingly, there is still no Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs at the State Department. The current acting head is Principal Deputy Alice G. Wells, whose most recent trips have been to India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

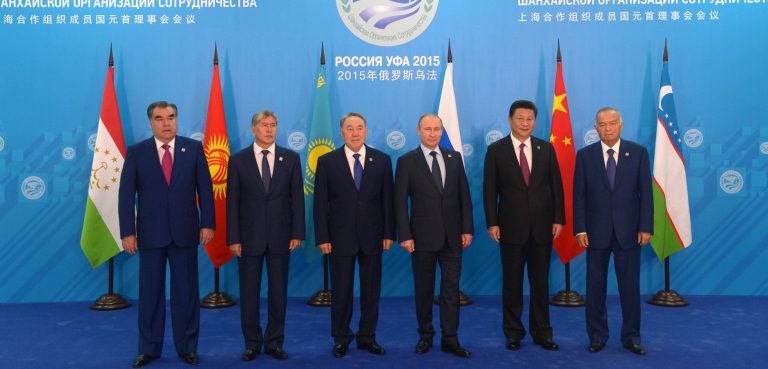

On the other hand, Moscow and Beijing have various outlets through which they maintain strong diplomatic and trade ties with the region, such as the Eurasian Economic Union, Shanghai Cooperation Organization, Collective Security Treaty Organization, Commonwealth of Independent States, not to mention China’s Belt and Road initiative. Additionally, both countries carry out major bilateral initiatives with Central Asian states. Examples include China’s landlocked port in Kazakhstan, or a late May report by IHS Jane’s which explained that Kazakhstan will purchase four more Mil Mi35-M combat helicopters from Russia, in addition to Sukhoi Su-30Sm warplanes.

Even more, as one Central Asian explained to the author, “Central Asian leaders meet with Russian leaders and Chinese leaders much more frequently than with their counterparts outside the region.” In other words, the two recent presidential meetings notwithstanding, “Washington needs to promote greater diplomatic initiatives with Central Asia if it wants to serve as a counterbalance to Beijing and Moscow… we need to reassure them that we will stick around,” a source in Washington added. Without a doubt, China and Russia have geography on their side, given that they border said region –advances in communications and transportation have yet to make geography fully irrelevant. In other words, Central Asia is their near abroad, while Washington is very far from Central Asia, and also has other foreign policy priorities nowadays.

Final Thoughts

Several commentaries over the years have supported a more ambitious U.S. foreign policy toward Central Asia: see Joshua Walker’s 2016 co-authored piece in The Diplomat or Ariel Cohen’s 2017 commentary in The National Interest. These two pieces discuss similar facts: Russia and China’s role, possibilities for greater trade with the U.S., the C5+1 initiative, and the development of Central Asia in general. Additionally, both authors warn that “the window of opportunity” (Walker) for Washington to increase its presence in Central Asia will not be open forever, hence “the United States cannot afford to just sit and look on from the bleachers” (Cohen).

Central Asia is a region with several moving pieces, including the level of cooperation (or lack thereof) among regional governments and the role of extra-regional actors. Washington’s default foreign policy tool to approach this geographically distant area is C5+1, which currently resembles more a noncommittal, occasional gathering of acquaintances rather than a serious mechanism for allied governments set on challenging Beijing and Moscow’s influence.

As things stand, the future of C5+1 is neither bright nor grim; it’s simply bland.

Wilder Alejandro Sanchez is a researcher who focuses on geopolitical, military, and cybersecurity issues.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect those of any institutions with which the author is associated, and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.

The author would like to thank the various Central Asian experts consulted for this commentary.