Following in the footsteps of fellow tech giant Apple, Samsung has reportedly opened talks for a multi-year deal to purchase cobalt from Congolese mining company Somika in an effort to secure its supplies of the highly prized metal.

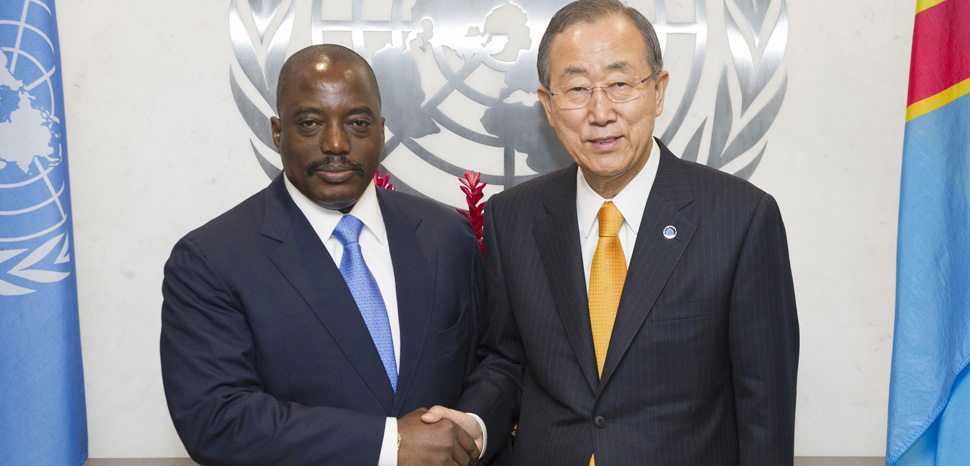

The conflict-ridden, politically dysfunctional DRC is home to approximately two-thirds of the world’s supplies of cobalt, a metal vital for manufacturing the lithium-ion batteries used in smartphones and electric vehicles (EVs). Despite such vast natural wealth, however, the Congolese people remain among the poorest on the planet (ranked 176th out of 187 countries by the UN’s Human Development Index). This is due in large part to Joseph Kabila, the country’s ruler since 2001, and his cronies occupying the highest levels of government.

With the mining industry in particular dogged by rumors of unethical practices, including hazardous working conditions and the widespread use of child labor, Samsung’s move to go to straight to the supplier is being seen as an attempt to guarantee ethical sourcing for their cobalt needs. The question is: With a dictator Kabila still calling the shots, will this road really lead anywhere?

Tightening his grip

Though Kabila’s presidential mandate came to an end in November 2016, he has exploited a legal loophole in the constitution which allows him to stay in power until his successor has been nominated. Since then, citing financial constraints and an inadequate electoral infrastructure, he has repeatedly postponed elections. Not surprisingly, his latest promises to hold elections by December have been met with growing skepticism by the international community and the Congolese people.

These promises look even less reliable when Kabila’s latest maneuvers are taken into account. Earlier this month – likely in recognition of the huge financial role that the country’s natural resource rents have played in keeping him in power – Kabila enacted a new mining code, which declares cobalt a “strategic mineral.” This designation allows the government to levy higher royalties on miners, as well as remove a stability clause that protected investment against changes to the fiscal and customs regime for 10 years.

Mining companies had lobbied against such a code for years, claiming its implementation would signal the demise of the cobalt industry in the DRC, but were forced into submission after a six-hour meeting with the president – though executives confirmed that international arbitration is still on the table. The new code represents a fivefold hike for miners, with royalties jumping from 2% to 10%.

Rotten to the core

In a country whose annual budget is a mere $5 billion, there is perhaps a case to be made that increasing governmental profits on national assets is a good thing – that is, if the increased royalties were intended to benefit the Congolese people. But even a cursory look at Kabila’s track record puts to rest even the pretense that the administration has the good of the people at heart.

According to a landmark report issued by international watchdog Global Witness, more than $750 million in mining revenues never reached national coffers between 2013 and 2015. Representing more than a fifth of all income from the mining industry, that figure swells even further (to $1.3 billion) when state bodies other than the national treasury are taken into account. Most of that money went missing after being paid to secretive state-owned mining giant Gécamines, which receives more than $100 million per year from private companies in the country’s mining sector, but passes on mere pennies to the state. Though Gécamines contributes little to the public coffers, it has somehow found the wherewithal to pay off loans for Dan Gertler, a friend of the president’s.

Mounting opposition

It is these kinds of practices that contribute to the country’s vast inequality, which – if corruption continues unabated – will only be exacerbated by the new mining code. Although Kabila has promised to step down after elections, his hardline stance regarding the mining industry suggests he has other ideas in mind.

Another factor which has facilitated Kabila’s grip on power thus far has been the regime’s constant harassment of the opposition and persecution of political leaders – but there are signs that the opposition’s disarray is changing fast. The emergence of a new coalition named “Together for Change” has united a fragmented political spectrum and could well pose the biggest threat to Kabila’s tenure to date. The movement is spearheaded by the businessman and politician Moïse Katumbi, who is currently in self-imposed exile due to charges of real estate fraud laid at his door by Kabila. Katumbi contends that all allegations are entirely fabricated and has vowed to return to his homeland by June to cement his candidacy.

For his part, Katumbi has condemned the introduction of the new mining code, claiming it only adds to the DRC’s climate of instability and further discourages foreign investment. If elected, he has promised to thrash out a fairer agreement with mining companies and stamp out corruption at the highest levels.

Paved with good intentions

Samsung’s decision to source its cobalt directly from the supplier might well represent the first step in respecting best practice guidelines, but it’s just a drop in the ocean when compared with the magnitude of the challenge. Without a more comprehensive reform of the entire mining and tax system, which would place transparency and integrity at every stage of the supply chain, Samsung’s move is little more than a “tick-the-box” exercise.

Unless such a scenario comes to pass, the proceeds from cobalt, copper, and the DRC’s myriad other exports will surely continue to find their way into the wrong pockets and stay there. If that happens, all the momentum Katumbi and the opposition can muster might not be enough to oust Kabila and save the Congolese people from decades of oppression and poverty.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.