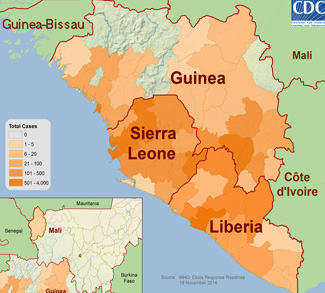

According to the latest data from the Center for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) the number of Ebola cases as of November 12, 2014 were reported to be 1878 in Guinea, 6822 in Liberia, and 5368 in Sierra Leone. These organizations have reported the official number of confirmed cases to be 14,068, however, according to Doctors without Borders (MSF) the number is actually much higher. To date, Ebola has killed over 5,160 people and has infected more than 14,000 people in West Africa.

To make matters worse, WHO has received less than half of the $260 million it deems necessary to handle the Ebola outbreak. Though an additional 15% of the total amount has been pledged to WHO, it is still waiting for 36% of the required sum. Out of 4,611 hospital beds planned for Ebola treatment centers in the three hardest-hit West African nations, just 24% are functioning, and only 4% of the some 2,636 beds planned for community care centers have been set up. Just 38% of the 370 or so burial teams the WHO plans to train are operational.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in September released worst-case modeling scenarios, forewarning that unless new processes are adopted to counteract the virus, between 550,000 people and 1.4 million people could be infected by mid-January in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

The World Bank Group said if the virus continued to surge in the three worst-affected countries and spread to neighboring countries, the regional economic impact could reach $32.6 billion by the end of 2015, dealing a calamitous blow to already delicate states.

The three nations at the epicenter of this outbreak are amongst the world’s poorest. All rank in the top 25 poorest countries on the planet, with Liberia being the least developed of the group. In Liberia 94.4% of the population lives on less than USD 2 per day.

Both Liberia and Sierra Leone are still trying to recover from bloody civil wars in the 1990’s that led to the deaths and displacement of millions of people. These conflicts destroyed much of the two nations’ health, governance, and industrial infrastructure, and by the time these conflicts were done both nations were on the brink of becoming failed states, which prompted UN peacekeeping interventions in both cases.

In 1994, the American journalist and geopolitical analyst Robert D. Kaplan published an essay in the Atlantic magazine entitled, “The Coming Anarchy” where he examined how scarcity, crime, overpopulation, tribalism, and disease were rapidly destroying the social fabric of our planet. He used the case of West Africa to best illustrate his hypothesis.

According to Kaplan in 1994, “West Africa is becoming the symbol of worldwide demographic, environmental, and societal stress, in which criminal anarchy emerges as the real “strategic” danger. Disease, overpopulation, unprovoked crime, scarcity of resources, refugee migrations, the increasing erosion of nation-states and international borders, and the empowerment of private armies, security firms, and international drug cartels are now most tellingly demonstrated through a West African prism. There is no other place on the planet where political maps are so deceptive—where, in fact, they tell such lies—as in West Africa.”

Kaplan’s analysis in 1994 was both predictive and frightening. His examination shed light on the magnitude of the challenges faced by these nations and foreshadowed why Ebola has been able to spread at such a rapid pace.

Legacies of Conflict and Political Instability

Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone are all states that suffer from a critical lack of infrastructure, brutal legacies of mineral/political conflict, child soldiers, endemic corruption, and poverty. Liberia and Sierra Leone both endured almost a decade of civil war that destroyed most of the two states already decaying infrastructures.

The Liberian civil wars led to the deaths of more than 220,000 people – mostly civilians – and the complete breakdown of sovereignty, law, and order. It displaced scores of people, both internally and beyond, resulting in some 850,000 refugees in neighboring countries.

The Sierra Leonean civil war lasted from 1991 to 2002, and it resulted in some 70,000 casualties and 2.6 million displaced people. The war was characterized by widespread crimes against humanity, including the use of child soldiers and systematic rape. The conditions that led to the war included a repressive state, dependence on mineral rents, the impact of structural adjustment policies, a disenfranchised youth population, the availability of small arms after the end of the Cold War, and meddling from regional neighbors.

Guinea, though in a slightly better position too has a history of authoritarianism, corruption, and military rule. Until the military once again took control in 2008 the country was ruled by President Lansana Conte, who seized power in a coup 24 years before. Since 2010, Guinea has held democratic elections and has made some progress that brought about greater political stability.

Decimated Public Health Infrastructure

The wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone decimated the two nation’s already weak infrastructures to the point of near collapse. This has further impaired their ability to act in a responsive way to curb the spread of Ebola.

Liberia

According to the World Bank, Liberia’s power generating capacity and national grid were completely demolished during 14 years of civil war. Piped water access fell from 15 percent of the population in 1986 to less than 3 percent in 2008. War also left the national road network in a state of severe disrepair. The country’s power generation capacity is barely one-tenth of the benchmark level of Africa’s other low-income countries. The cost of generating power is exorbitant, and the power tariff is three times the regional average. Addressing Liberia’s public infrastructure needs will require sustained expenditures of between $350 million and $600 million annually, mostly to fund power and transport. In the mid-2000s, with all sources of spending taken into account, Liberia spent around $90 million a year on infrastructure. An additional $17 million was lost to inefficiencies, such as underpricing of power.

According to the WHO, the Liberian health system was also destroyed in the war: of the 293 public health facilities operating before the war, 242 were deemed non-functional at the end of fighting due to destruction and looting. Doctors, nurses, and other health workers fled the country, leaving just 45 doctors to care for a population of 4.5 million. Outside Monrovia, where humanitarian agencies provided some services, most of the population has little or no access to health care. The government of Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, elected in 2005 in the country’s first post-war democratic election, faced a dire health situation.

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone’s 11-year civil destroyed the country’s infrastructure, and rebuilding the road network and ports while improving the electrical, water, and telecommunications infrastructure is proving difficult. According to the World Bank, electricity access stands at only 1-5 percent of the urban population, and 0 percent in rural areas. The water and sanitation sector faces similar challenges, as only 1 percent of the rural population has access to piped water.

The civil war brought all of the health and economic infrastructures down to zero during the 10 years. Many clinics established by the government were completely demolished. Many people moved from the countryside into main cities and towns, which compounded the poor health and sanitation situation. Today, Sierra Leone has one health worker for every 5,260 people.

Failing States, Anarchy, and Porous Borders

At a recent high-level meeting WHO head Ms. Chan remarked that, “the Ebola epidemic threatens the “very survival” of societies and could lead to failed states.” She went on to say that, “I have never seen a health event threaten the very survival of societies and governments in already very poor countries, I have never seen an infectious disease contribute so strongly to potential state failure.” She further warned that Ebola was a “historic risk” and that the economic impact of “rumors and panic spreading faster than the virus,” citing a World Bank estimate that 90% of the cost of the outbreak would arise from “irrational attempts of the public to avoid infection.”

Anarchy and a lack of law and order is nothing new to West Africa. Since the end of the civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone, the governments in Freetown and Monrovia have exercised little control outside of the two capitals. The interiors of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone and most states in the region can be categorized as ungoverned spaces. The lack of the ability of West African governments to exercise control over their territories has given rise to West Africa becoming a transit point for narcotics, human traffickers, conflict minerals, terrorist organizations (AQIM) and smuggling. According to the Economist, “the UN reckons that cocaine worth $1.25 billion passes through West Africa every year, more than the national budgets of several countries in the region.” In addition, many national and international criminal organizations have managed to gain a foothold in the region. Such groups have been able to corrupt public office holders and military officials, use former child soldier gangs to do their bidding and to operate without fear of being prosecuted. Guinea is at the eastern end of “Highway 10”, the name given by drug enforcement agents for the 10th parallel north of the equator, the shortest route across the Atlantic, used by traffickers over the past 10 years to smuggle Latin American cocaine destined for Europe. United Nations experts estimated in 2013 that some 20 metric tons of cocaine, mostly from Colombia and Venezuela, passed through West Africa, which has become an attractive transit point as U.S. and European authorities cracked down on more direct routes.

State security, border control, and police forces in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone also lack the capacity, numbers, and authority to maintain law and order and sovereignty over their respective nation’s territories. Rural borders between these three states are porous and under-policed. This has allowed Ebola to spread from Guinea to Liberia and Sierra Leone at such a rapid pace. Dr. Thomas Frieden, the director of the Centers for Disease Control, admitted that Africa’s porous land borders made the Ebola crisis worse.

A Call to Action

International and regional actors must act now to bring Ebola under control. The global community must move beyond the rhetoric, stigma, and fear and act to deliver the funds they have pledged. To date the United States has decided to send 3,000 military personnel to construct treatment centers and train health workers in Liberia, the UK military is providing further support to Sierra Leone and the French military has committed to opening a military hospital in Guinea. China has also sent medical staff to the region and doctors from the small nation of Cuba have been essential players in the Ebola response.

Though these are steps in the right direction, The International Crisis Group (ICG) believes, “it will not be nearly enough.” In September the ICG stated in a situation report that, “The international community must allocate more personnel, resources, and strategic planning not only to the medical response but also to the longer-term problems of food insecurity, political unrest and poor governance, to build resilience to these sorts of crises. In the near term, the international community should consider holding an emergency donors conference, including international financial institutions and health organizations, to coordinate action against a disease that indeed presents, as the resolution says, a threat to international peace and security.”

In conclusion, one must not forget that the Ebola outbreak has not occurred in a vacuum and that the region’s geopolitical challenges have allowed the disease to spread across regional and international borders unchecked. The international community must not only act quickly to contain the current Ebola outbreak but also go further by addressing the reasons why this rare tropical virus was able to become an epidemic. Focus and support must also be on allocated to the political, human security, and economic challenges that the epidemic has created. Failing to adequately address the current crisis will not only lead to the proliferation of failed states but could also result in Ebola becoming a global pandemic, in which case the human and economic costs would be astronomical.