Newly appointed Belgian Transport Minister Elke Van den Brandt is one of several politicians who rode to power on the coattails of last May’s ‘Green Revolution,’ a distinct, noticeable surge in support for environmental parties across Europe. And like many politically unique leaders, Van den Brandt has carved out a legislative niche of priorities different from her competitors in Brussels. Her top issue? Traffic congestion.

Yeah, you read that right. Not adjusting the tax rate, not social justice, or healthcare spending. It’s simple yes, but nonetheless extremely important. Brussels is renowned across Europe for its terribly clogged infrastructure and after years of mainstream left-wing and right-wing governments’ failure to address the problem, Van den Brandt capitalized on it as a real, genuine threat to the stability of lives of people in the region. A growing issue that wasn’t glamorous enough for typical politicians to take the time to solve; luckily for her and the Greens, they are anything but typical.

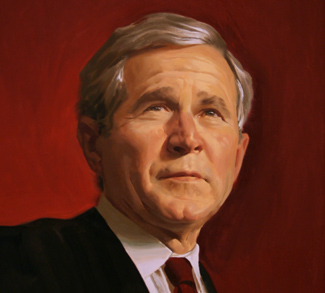

At only 39 years old, Van den Brandt is very much a child of the 80s. Born in Antwerp, she got her start at the city’s local level, helping do the paperwork for the government’s housing, education, and poverty projects. In 2009, she was elected to Parliament. Ambitious from the start, Van den Brandt’s personality shamelessly, although obviously unintentionally, matches that of her party exactly: young, forward-looking, and trailblazing.

The coalition government formed in July by an alliance between the insurgent Greens and typically dominant Socialists has already rolled out an impressive amount of infrastructure projects in her short time as minister, including plans for 7 new tramlines and a 30% increase in the city’s bus capacity. But from the 25th floor of the administrative building where her office is located, ironically within sight of the north train station, Van den Brandt plots her next move. As does her movement all across Europe

The “Quiet Revolution,” as The Guardian termed it, weeks after the election was a pleasant surprise to many, who had expected the far-right to continue making political gains. Instead, Green parties across the continent swept into power, winning a total of 69 seats in the EU Parliament, including 22 from Germany, 12 from France, and 11 from the UK. Even Dublin elected its’ first Green MEP in over two decades.

“We are very happy about it but it also leaves us with a lot of responsibility; people didn’t vote for us just as a protest – it’s for policy,” said Terry Reintke, a newly elected German Green MEP, who described the surge as a “green wave.” “Obviously the climate crisis is going to be a priority, particularly because the window for action is very very short. But it’s too narrow an analysis to say the support was only because of that. People also voted for us in large numbers because we are also a very credible party on democracy, rule of law, and human rights. We see the European Union as not just an economic union but a union of values. It has to be more equal and socially just. This will be a priority for us in negotiations.”

It’s not just EU elections that it’s affecting either. Not long after the surprise sweep, polls began showing retiring German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s CDU falling behind the Greens, who took the lead with a solid 27% projection of the national vote. Perhaps even more surprising is that this turnaround in fortune comes just after the 2017 contest where the Greens didn’t even obtain 10% of the national vote. Switerzland’s elections in October of 2019 offered a similar result, propelling the Greens into power for the first time in decades, even placing higher than a previous member of the country’s ruling coalition.

“In an increasing number of countries, we’re a real player, a real polar force now, and we want to translate that to the European level,” Reinhard Bütikofer, a longtime German Green lawmaker, told an event on Germany’s election night.

The Greens are not only proving themselves a popular choice because of the growing climate crisis that many across Europe feel the main parties have done little to stop, but also because they are not tied down by any major, ideological obligations; they have proven they are flexible as well as realistic enough to address real, everyday problems EU citizens face that other parties have forgotten about.

While Macron and Merkel gallivant around the press rooms in Paris as well as Berlin, their attention collectively laser-focused on current affairs in Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, domestic issues of real importance that affect the people that put these leaders in the office aren’t getting the attention they deserve. Without question, the current withdrawal of American forces from the region does require scrutiny and careful policy analysis from European leaders, but frankly, it’s not a hill to die on.

And what are the Greens talking about? Real issues. Climate change, city planning, local infrastructure projects and yes, even traffic congestion. It’s not exciting, and it’s certainly not even close to interesting; but important? To the voters, yes. To the pundits on TV who make a living off of keeping our grandparents up past 10 pm with frustratingly thin, vague rants about whatever is dominating that week’s news cycle? No. But they don’t get to decide what’s important; we do.

Van den Brandt’s determination to resolve kitchen table issues that have plagued Belgians for decades, clearly, is a broader representation of the political dynamic that Green politicians all across Europe are showing their constituents.

But if you think she’s anywhere close to stopping, you’d be wrong. Currently, the minister is pushing hard to make all public transport for those under 25 and older than 65 free, and she’s working hard to help diminish Brussel’s large pollution contribution. But still, she understands that the region can’t fight the good fight all on its own.

“Brussels is not an island,” she said. “We’re surrounded by other regions, so we’ll have to work together.”

This crusade to fix the mundane, unexciting problems that have plagued large cities like Brussels have separated the Greens all across Europe from their traditional political counterparts. It seems that in this new age of partisanship, as France struggles with the yellow vest protests, Britain’s Parliament slugs out the details of Brexit, and Germany deals with the rise of the alt-right, Green is starting to mean something else besides environmentalism. For Europe, Green means progress.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any institutions with which the authors are associated.