Roughly three weeks left on the calendar, a turbulent year of 2016 is rapidly coming to an end. With a constant stream of geopolitically-significant events and the accompanying information overload (or at least information filtered through commentaries of all stripes for those among us that are news junkies), many of the shocks we experienced this past eleven months perhaps seem like a distant memory.

The year began with some deep shake-ups in Eurasia. There was the ensuing chaos in the stock market and economy of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which is still in crisis mode currently, with Beijing attempting to prevent capital flight (renminbi has fallen drastically against the dollar [5.8%] this past year). On top of this is the Chinese government’s continued expansion into South and East China Seas, causing major tension among Asia’s Pacific Rim states.

Looking at the other side of Asia, there was the collision between the Islamic rivals of Shiite Iran and Sunni Saudi Arabia (both contending for dominant position in the immediate region). The Syrian civil war – which has morphed into a proxy war of various states – and the catastrophe of the Islamic State’s avowed restoration of the Caliphate, which has caused havoc in the Middle East (by nullifying the borders instituted by the Western imperial powers: “Sykes-Picot? What’s that? Can I dip that in hummus? [Laughter] ”).

Members of the Islamic jihad movement joined the chorus of attacks targeted at what the perpetrators perceive as infidels. This phase of current crisis in the MENA region rose from the after effects of the 2003 Iraq War (and the premature US military pullout enacted by the Obama administration) and the so-called Arab Spring which occurred under the policies of the past two US presidencies. The situation has been further exacerbated by the military intervention from Moscow in Syria, setting up a deeper presence in the Middle East that is more overt than the Cold War years (back then characterized by support for various secular Arab regimes).

We also witnessed – and continue to witness – seemingly never-ending political and social disturbances in European Union states surrounding the flood of migrants from the MENA region. 2016 commenced with news of mass number of sexual assaults at a New Year’s celebration in Germany, and uprisings in form of protests and violent riots occurred thought the year. The world political and financial establishments were shaken by the revelation of the Panama Papers in late spring. The deep fracture of the EU, accompanied by rise of domestic populism in states both greater and lesser in power, was only renewed by the results of Brexit referendum in late June. As many of the Brexit supporters (both domestic and across the globe) partied it up after the victory, Islamic State operatives (suspected to be from Northern Caucasus and Central Asian states), struck Atatürk International Airport, leaving 45 dead and bringing to the forefront the debate over EU security in light of Brexit.

For both the European Union and the MENA region, the seeming demise of the legitimacy of artificiality-created regimes of the 20th century is at the essence of respective crises (‘post-WWII order’ integration for the EU and ‘post-WWI order’ disintegration for the MENA).

The Russian Federation, fifteen years since the collapse of Soviet Union, has been surging again with imperial vigor, with spirited intervention into its periphery, on all of its flanks.

The latter half of the year began with a continuing string of terrorist attacks that struck the EU, most notably the mass slaughter of 86 lives in Nice, France during the Bastille Day celebration on July 14. While the world’s attention was glued to that gruesome butchery of an Islamist terrorist mowing down the celebrants with a truck, a coup attempt ensued in Turkey, with putschists firing on their fellow citizens. The event killed at least 290 and wounded over 1400.

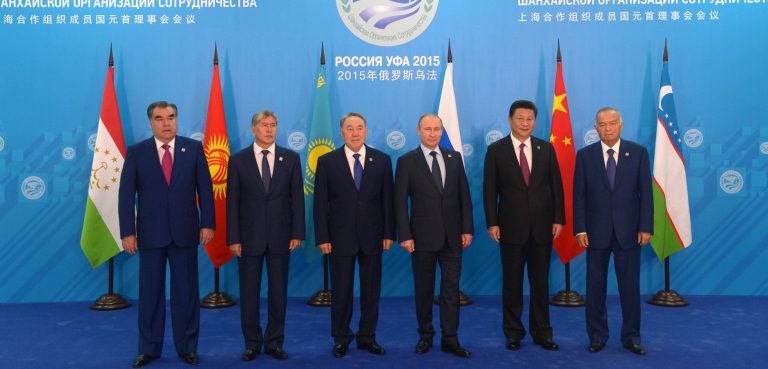

While the possibility of the coup being staged by Erdogan’s regime has been raised, the Islamist-leaning President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who expressed that the coup was a “gift from God,” responded swiftly with an intense crackdown. He called for support from those who are loyal to him, solidifying his power over the state apparatus. Erdogan promised a “New Turkey,” increasingly marginalizing populations that are secular-oriented and pro-Western. Erdogan has pointed out that Ankara may shift away from its EU-considerate policy to an Asia-leaning policy, perhaps joining Shanghai, Moscow, and various capitals of Central Asian states (many of them having Turkic heritage as well) to comprise an updated version of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). The SCO – a counter-NATO land-power alliance with territory roughly corresponding to a good portion of the old Mongolian Empire – is a security bloc dominated by illiberal authoritarian regimes.

Moreover, Erdogan also has been stressing that trade between Russia, Iran, and the PRC should be conducted in local currencies, in an attempt to prop up its sliding lira. Ankara also has recently held bilateral talks with Tehran, engaging in some warming of relationship between the two capitals which has had some tensions during the secularist years before Erdogan’s Justice and Development party (AKP) took control of the levels of power. The rise of Turkey as a strong Islamist state would also concern the Communist Party running the People’s Republic of China, which has its own problem regarding a Uyghur secessionist movement in East Turkestan (Xinjiang province), potentially creating a movement to form a jihadist statelet in Central Asia. Recall that series of protests broke out in Turkey after Beijing’s alleged maltreatment of Uyghurs (and government-supported large-scale colonization of East Turkestan by the ethnic Han population) during the month of Ramadan in 2005. Asia Minor and Central Asia are connected by history of a common people.

The rise of authoritarian regimes is not limited to Turkey. Indeed, so far as Eurasian geopolitics is concerned, consolidation of the state authority of major regional players, and even the resurrection of old imperial order – one might call it ‘neo-imperialism’– seems to be the track upon which history is currently unfolding. Gone are the days when liberal democracy’s march across the globe seemed inevitable. 2016 may stand at history’s threshold of a new era.

The Russian Federation, fifteen years since the collapse of Soviet Union, has been surging again with imperial vigor, with spirited intervention into its periphery, on all of its flanks. It has been a customary mainstream view to point out that Russia and its security has been threatened due to the gradual eastward march of NATO since the Soviet collapse. It is commonly argued that Russia, due to repeated invasions by foreign forces throughout its history (such as Mongols, French, and Germans), traditionally envisions its borders as a vague regional “plane” rather than clear-cut “line.” Thus, a threatened Moscow is engaging in a struggle for security to ward off any encroaching powers and constellation of alliances by bolstering its militarization practices, especially after the Crimean crisis of 2014.

However, there is another side to this narrative. Janusz Bugajski, Senior Fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) headquartered in Washington DC, points out that Russia’s quest for imperial status (at least to unseat US position as the unipolar power) began shortly after Soviet collapse, as early as 1993. Russia’s previous incarnations have all been imperial entities, being inheritor of Byzantine Empire. Russian regimes styled itself as ‘New Rome’ after accepting Eastern Christianity in the 10th century (and especially after the fall of Constantinople), effectively becoming the ‘Northern Roman Empire.’

According to Bugajski, Russian Foreign Ministers Andrei Kozyrev and Yevgeny Primakov (although more overtly under the latter than former) during the 1990s had already laid the intentions and conceptual tracks for Russian re-imperialization. Bugajski notes that Moscow is exploiting the pretext for provision of national security (although Eastern European states joining NATO may not necessarily be military/security threats to Russia, Russia loses significant influence over policies enacted in the capitals of these states) to further expansionism into regions of former Soviet influence. This strategy is not pursued merely through military tactics, but also through state-sponsored energy giants (such as Gazprom, which operates as somewhat of a private government in itself, possessing a private military, cities, hospitals and schools), exploiting EU energy dependency. Under leadership of Vladimir Putin, this re-imperialization process merely accelerated since 2000 (although seeming cooperation with the U.S. after 9/11 was most likely a temporary tactical move to use the international climate to further Kremlin’s grand strategy). The Kremlin has utilized multi-state alliances such as the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO, noted above in relation to Turkey) and Eurasian Economic Union (EEU– formed in January 2015) to gain influence and establish protectorates in Central Asia in an attempt to block off Western (and also PRC) influence.

In March 2014, the geopolitical move to secure influence in grain-producing Ukraine (Ukraine also being the location of the Kievan Rus and Principality of Kiev, the roots of the Russian heritage) and access to the Black Sea (via securing the Crimean peninsula) was implemented after the ousting of Russia-leaning Viktor Yanukovych. The Ukraine crisis in turn started a new round of tension and wargames between Russia and US/NATO states. In 2016, the geopolitical battle spilled into cyberspace. Accusations of Russian involvement in US presidential race have been hurled about, with assertions of Moscow-backed hackings and passing sensitive information off to Wikileaks (Russian officials continue to deny these charges). FireEye Inc., California-based cybersecurity firm, noted that Moscow practically weaponized the social media-sphere, in essence unleashing another wave of converting cyberspace into a geopolitical battleground, engaging in psychological warfare operations to influence the outcome of the US presidential race.

Moscow’s exploitation of populist leaning politicians is not limited to Donald Trump; Viktor Orbán, the Hungarian Prime Minister known for his hardline stance against the mass-entry of migrants from the MENA region, has been utilized by Moscow since his accession to his current office in 2010. This is used as an instrument to counter-balance the EU. Orbán, who has in 2014 declared that he seeks to end liberal democracy in his country (taking his inspiration from Russian and Turkish statecraft, giving rise to the phrase “Putinization of Hungary”), has remained quite neutral in face of the Ukraine crisis and recent Russian expansionism. Hungary has functioned as an agent for Moscow by extending Russian interests throughout Central European region. Moscow uses the energy card (gas and nuclear) to keep Budapest close to the Kremlin, and prevent the EU from building a unified energy policy in Central Europe.

One of the founding fathers of the classical geopolitical theory, Sir Halford Mackinder, wrote in his work Democratic Ideals and Reality (1919) on the interconnectedness of Europe and the rest of the Eurasian mega-continent:

Americans used to think of their three millions of square miles as the equivalent of all Europe; some day, they said, there would be a United States of Europe as sister to the United States of America. Now, though they may not all have realized it, they must no longer think of Europe apart from Asia and Africa. The Old World has become insular, or in other words a unit, incomparably the largest geographical unit on our Globe.

As Mackinder has predicted, the EU project has seen major signs of stalling due to political situations in Asia (the eastern flank of the ‘World Island’) and Africa (southern flank of the ‘World Island’): Russia intervening in its affairs (the Ukraine crisis and activities in Hungary) and the migrant crisis. All the while Islamist terrorism continues to rekindle the spirit of national sovereignty throughout the Union.

Looking farther south, the Islamic Republic of Iran, the Islamized modern incarnation of ancient Persian empires that coexisted and warred with foundational empires which the West traces its heritage (Greek and Roman), has become increasingly brazen in its operations against the United States and is increasingly intervening in its immediate region as a result of the Iran nuclear deal.

Now, well over a year since the signing of the agreement in July 2015, and nearly one year since the agreement went into effect in January of this year, the consequences of the deal have opened a Pandora’s Box of whose ghoulish contents may wreak havoc across the globe.

While political and commercial leaders in the EU have flocked to Iran as if on a religious pilgrimage to secure sweet contractual deals in areas of investments and tap into the massive economic powerhouse, not only has Tehran conducted ballistic missile tests in October and November of 2015 (and again in March of 2016, and attempted another test in July for missiles integrated with North Korean technology), German intelligence has pointed out that Tehran has already tried multiple times to violate the deal via attempts to secure banned equipment. Additionally, the danger of Iran acquiring nuclear technology may inflame weapons proliferation in the MENA region, sparking an updated nuclear arms race in a place not known for stability, one that would make the Indo-Pak arms race of the 1990s look tame by comparison.

The latest provocation involved a military vessel of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard pointing its weapon at a US Navy helicopter while engaging in a flyover above international waters in the geopolitically significant Strait of Hormuz. 2016 was replete with similar provocations by Tehran-sponsored forces aimed at the U.S. Meanwhile, Tehran, which has praised the Arab Spring- triggered political revolutions in the MENA region, has renewed its ties to Hamas , uniting in targeting Israel, in effect trapping the Jewish state with Hezbollah in Lebanon, located to the north. (The relationship between Tehran and Hamas collapsed in early months of 2012 after Tehran proceeded to prop up al-Assad regime in Syria.)

Mackinder, in his Democratic Ideals and Reality, noted the importance of the Levant (singling out the city of Jerusalem) in the following way:

If the World-Island [Eurasia] be inevitably the principal seat of humanity on this Globe, and if Arabia, as the passage-land from Europe to the Indies and from the Northern to the Southern Heartland, be central in the World-Island, then the hill citadel of Jerusalem has a strategical position with reference to world-realities not differing essentially from its ideal position in the perspective of the Middle Ages, or its strategical position between ancient Babylon and Egypt.

Considering that Mackinder goes on to note the importance of the Suez Canal to MENA geopolitics, Tehran’s forces gaining a foothold in a strategically significant region in Eurasian geopolitics cannot be understated. Iran’s dominance would, if not merely symbolic, shake the world.

Iran, as noted in a previous piece on the Sudan’s place in the MENA geopolitics, has repeatedly engaged in colluding with regional extremist powers in its quest for influence and dominance of the regional order. Tehran has been an integral part of what it calls the “Axis of Resistance” against the West’s intervention in the Middle East (plus Israel), and manifested this role in manners such as lending full-fledged support to the al-Assad regime, to further its power-projection capabilities in the region, if even in the event of a regime collapse.