“We are currently living in an age of change and uncertainty. The international order – based on the rule of law – is receiving a serious challenge. In such environment, the importance of global strategic partners such as Japan and Great Britain with shared basic values such as liberty, democracy, rule of law, and human rights, has only increased.”

These are the words spoken by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe as he and his British counterpart, Prime Minister Theresa May, commenced their joint press conference on August 31 during May’s first trip to Japan. The joint press conference emphasized various topics such as the growing importance of the British role in Indo-Pacific security, information sharing in preparation for the 2019 Tokyo Rugby World Cup and 2020 Summer Tokyo Olympic/Paralympic Games, cyber security, cooperation in counter-terrorism, the importance of the success of post-Brexit Britain for the world’s prosperity and continuation of the free-market system, demographic challenges facing both countries in the coming decades, and the like.

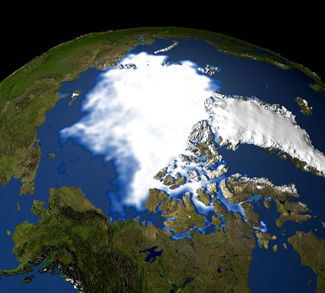

May’s three-day trip to a fellow Eurasian maritime power on the eastern end of the mega-continent was in a certain way an echo back to the Anglo-Japanese alliance, a system established to counter an expansionist continental power over a century ago. Indeed, in certain respects both island cultures are somewhat ‘misfits’ in relation to their nearby continental neighboring states. May appraised the Anglo-Japanese relationship as “natural partners…outward looking, democratic, free-trading island nations with global reach” in the press conference. It was the Russian Empire in the bygone days of the Great Game. Today, it is rising multi-polar Eurasian system headed by a constellation of rising states – former empires – that has steadily been asserting control over its own sphere of influence. A prevailing meme of the post-Cold War era was the decline of nation-states, the triumph of democratic internationalism, and the rise of non-state networks and non-state based asymmetric warfare that would render the institution of the state as meaningless or outdated; all this has seemingly turned out to be an illusory mirage.

Indeed, May’s visit to Japan featured a visit to JMSDF Yokosuka Naval Base, which stations JS Izumo, a helicopter carrier which recently returned from a three-month long voyage in the Indo-Pacific rim. During the voyage, the naval vessel attended multiple security-related events in the region, notably the International Maritime Review 2017 hosted in Singapore and the Malabar 2017 naval exercise in India. On board the JS Izumo, Japan’s Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera explained to May that the original Izumo a century ago was constructed in Great Britain, and Britain’s assistance in the Russo-Japanese War was a defining element that helped Japan secure its victory. (The victory successfully was able to temporarily halt the presence of expansionist Russia off of the Korean peninsula, a geopolitically significant element in Japan’s preservation of domestic security. The peninsula that juts out toward the archipelago may be comparable to Cuba vis-à-vis the United States, which its intelligence organizations during the Cold War were active overtime to keep Soviet influence and nuclear weapons off the island.) Onodera proceeded to inform May that the Izumo was also active in the Mediterranean Sea during World War I, assisting Great Britain in its operations. May in turn, noted that the current visit is a reflection of the strengthening of the bilateral defense partnership in past years.

After the Yokosuka visit, in the afternoon of August 31, May participated in the National Security Council (NSC) meeting, becoming the second non-Japanese head of government invited to attend the briefing. The first was former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott in April 2014. (Australia, like Great Britain, is a maritime power indispensable to the security and stability of the Asia-Pacific region.)

It has been reported that the NSC meeting consisted of talks regarding provocative actions taken in recent months by Pyongyang (especially the recent Hwasong [“Mars”]-12 Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile [IRBM] flyover on August 29 (the anniversary of the proclamation of 1910 Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty). Lest one thinks that the Pyongyang’s success in development of Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) over this summer – a project suspected to be assisted by elements wired into Moscow or Beijing or both – is strictly an issue for East Asian security and the United States, Great Britain is well within the range capabilities of the said weapon system. As North Korea’s arms-trafficking networks span throughout Eurasia (particularly Iran and Syria being notable), this new development should be of concern for London as well. Additionally, it has been suspected in April 2017 that London property has been used as a link in financing the DPRK nuclear weapons program. The DPRK of course has recently taken another stride toward massive global security crisis by engaging in a sixth test of its nuclear arsenal. If the crisis spirals out of control, by accident or otherwise, it may cause catastrophic upheaval not only regionally but on the global scale, especially in the economic sphere.

On September 1, Foreign Minister Taro Kono remarked during a press conference that it is the plan of the two maritime powers to work towards strengthening the bilateral relationship from that of partnership to alliance. In October 2016, a joint military exercise involving RAF Typhoon fighter jets was held, the first time combat drills were held involving non-US military (and this to be followed up by joint exercises involving ground forces from both countries in 2018). It was made official in March this year that there are projects in the works regarding joint development of next-generation stealth aircrafts. Times have changed. Two decades pass after Hong Kong was handed back to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Great Britain is returning to Asia.

Multi-polarization of the planet’s geopolitical architecture – and particularly that of Eurasia led by major authoritarian regimes – seems only to be accelerating. In January 2017, the National Intelligence Council (NIC) under the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) published Global Trends: Paradox of Progress, a study that concluded the following on current global trends: “The next five years will see rising tensions within and between countries. Global growth will slow, just as increasingly complex global challenges impend. An ever-widening range of states, organizations, and empowered individuals will shape geopolitics.” The global turbulence between 2017 and 2022 may have major impact on history for the foreseeable future, and the rise and alliance formation of these major powers is a key axis upon which the history is flowing.

Much could be said of this assortment of illiberal regimes and their regional designs, but there is no denying that the primary topic of discussion in the recent Abe-May meetings was that of regional security, notably the stabilization and maintenance of an open and free of maritime environment in the Indo-Pacific region, which in turn will provide stability for not only Eurasia but international society at large.

Great Britain has become more involved in Eurasian affairs since the middle of this decade, increasingly diversifying from its traditional post-World War II junior partnership status with the United States. Despite tensions over the Syrian civil war and the Ukraine crisis, London has attempted to gradually improve relations with Moscow. This more active engagement with Eurasia is true particularly within the economic realm. London is getting involved with geopolitical-economic designs such as the Belt Road Initiative (BRI – formerly known as One Belt One Road [OBOR] Project) and its supporting financial institution, Beijing’s newly launched Asian Infrastructural Investment Bank (AIIB).

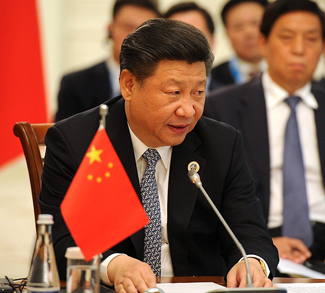

The BRI mega-project, launched in September 2013 by PRC Premier Xi Jinping is inherently a geopolitical program. Rooted in Sir Alfred Mackinder’s geopolitical proposal for a hegemonic power to unite continental transportation routes of Eurasia and Africa (what Mackinder called ‘the World Island’) and support those routes with additional maritime routes, the idea is a profound example of the importance of classical geopolitics in the 21st century.

Not only is Beijing working overtime to actualize this strategic project, it is pulling major Eurasian state actors into the BRI orbit. In May 2017, a BRI forum was held in Beijing, moving the megaproject forward. Moscow is enacting a series of moves to take part in BRI, marketing Russia as an integral cog to its success. Iran, which is economically dependent on petroleum exports to the PRC, is considered by Beijing as an indispensable link in the BRI project. Tehran welcomes the BRI, not only having post-2003 Iraq under its wings due to the ironic ‘success’ of Shiite Iraq’s democratization (recall that Ahmed Chalabi, whose information network led to the Iraq War was an Iranian agent), but also Qatar increasingly under its influence due to Riyadh and other MENA capitals’ suspension of diplomatic relations in summer 2017. Tehran has a freer hand in engaging in trade post-JCPOA agreement, and Beijing and Tehran are also moving forward on defense-military cooperation as well.

Needless to say India, PRC’s geopolitical rival, is not simply sitting around waiting to be outdone. New Delhi is bringing the International North South Transportation Corridor (INSTC) program out of the vault [originally planned at the dawn of the 21st century] to counter Beijing’s ambitious corridor project.

The attention of the White House, and that of the 24-hour news cycle of the US establishment media, has been increasingly domestic

In the words of Edward Mead Earl (1894-1954), a specialist in military and foreign relations: “Only in the most primitive societies, if at all, is it possible to separate economic power and political power… When the guiding principle of statecraft is mercantilism or totalitarianism, the power of the state becomes an end in itself, and all considerations of national economy and individual welfare are subordinated to the single purpose of developing the potentialities of the nation to prepare for war and to wage war.”

As such it is impossible to view the BRI project, spearheaded by the PRC – a classic example of a totalitarian state – as some sort of charity work for Eurasia that is severed from Beijing’s political and strategic interests. The narrative that AIIB is simply dedicated to Eurasia’s infrastructural development (via export of PRC’s labor resources and capital, which is according to Vladimir Lenin, a characteristic of imperialism) only gets partial picture. When it comes to strategic thinking, even ‘anti-imperialist’ regimes formulate policies in the manner of their imperialist counterparts.

The BRI-AIIB package is targeted at redrawing the entire geopolitical and economic (rooted in Post-World War II Bretton Woods system) architecture of the World Island. How will it turn out? Despite Beijing’s claim of its commitment to a free market system (selling itself as a counter to protectionist policies proclaimed by US President Donald Trump), the PRC remains highly protectionist and regulated. In 2016, corporate investment in the BRI project actually declined, and only 29 out of 65 participating states sent head of state class delegates to the May 2017 BRI forum. The project is still in the launch phase, and despite its fanfare, the success of the project could be said to be still in the fog.

Since early 2015, Great Britain has involved itself in the construction of this new geopolitical program, as well as a host of Eurasian states (not to mention Canada, which would make the project a global scale, involving the western hemisphere). Lawrence Summers, former US Secretary of Treasury, has lamented these developments as a dramatic loss of US influence. The former Cameron cabinet (astoundingly, a conservative government) joined hands with Beijing in March 2013, and later that year massive investments in the British economy were promised by Beijing, and is ongoing even after the Brexit Referendum of 2016.

The attention of the White House, and that of the 24-hour news cycle of the US establishment media, has been increasingly domestic (with the exception of DPRK issue). Most recently, issues include the disaster of Hurricane Harvey and the rescission of the DACA program. Meanwhile, key states in Eurasia have been taking active steps in attempting to secure vital interests in a rapidly transforming geopolitical landscape. Prime Minister May’s visit to Japan and the program of strengthening the UK-Japan bilateral relationship to near-alliance is yet another instance of this reshuffling of the geopolitical order, inherent in the multi-polarization of post-Cold War international society.

This geopolitical reordering is not an exception even in the western hemisphere. US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson (presumably the Trump administration itself) is unfortunately engaging in short-sightedness, leaning toward backing away from the international promotion of liberal democratic values and human rights. Despite principles of liberal democracy and human rights being misused in the past by selective regimes, this misuse does not negate the principle itself. Take for another example the U.S. neighbor to the north. Canadian Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland commented this summer that Canada is willing to go its own way rather than to walk the path of economic protectionism that has been one of the hallmarks of the Trump administration. To the south, Mexico is seeing an upsurge in support for Andres Obrador, a socialist populist candidate as it looks ahead to presidential elections in 2018.

There has been speculation over the increasingly interventionist role of the state, not only in security matters but also in the economic sphere in the coming years. Maritime states giving nod to liberal principles will go a ways in maintaining liberalism in what it seems like expanding chains of authoritarian illiberalism across the planet. Perhaps partnership between the ‘global’ Great Britain (freed from Brussels’ bureaucracy) and Japan may help become an anchor in this and function as a model as the world approaches the third decade of the 21st century.