It’s been a turbulent start to 2020 for one of Mexico’s most prominent family businesses. Since January, the Oseguera González family has struggled to keep business as usual. The COVID-19 pandemic has shuttered suppliers and closed key export markets. Problems with staffing and inventory have popped up abruptly. Legal issues are causing family drama. The family’s finances will probably take a hit. Such challenges surely resonate with millions of family-run firms across Mexico as COVID-19 restrictions take their toll. But the Oseguera González clan isn’t just any family. They run one of the world’s most dangerous crime groups, the Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG).

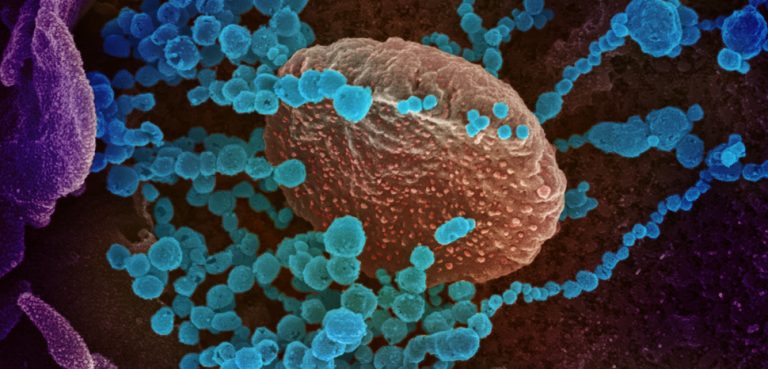

The difficulties for Mexico’s most dangerous family began in January, when Chinese public health measures put in place to fight COVID-19 started to disrupt the trade in synthetic drugs. The CJNG imports precursor chemicals from China to manufacture methamphetamine and fentanyl, and China serves as a key export market for the finished products. Yet, a prominent Chinese partner of the CJNG, the Zheng cartel, has found its operations and communications constrained by the virus lockdown, according to 5 March reporting from Mexican radio outlet Nación Criminal, which cited an intelligence source in the Mexican Attorney General’s Office.

As the cartel struggled with supply, the Oseguera González family faced legal problems. On 20 February, Mexico extradited Rubén Oseguera González, the son of CJNG leader Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, to the United States to face drug trafficking and weapons charges in the District of Columbia. The following week, Rubén’s sister appeared at a federal courthouse in the capital to see her brother and was promptly arrested for alleged violations of US sanctions law.

Less than two weeks later, American authorities unveiled actions against the cartel’s distributors. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) announced arrests of more than 600 CJNG associates across the United States and drug seizures in excess of $22 million. The raids specifically targeted the CJNG’s footprint in New York, and the DEA’s St. Louis Division continues to investigate CJNG operations in the Midwest.

These setbacks to arguably the most powerful criminal force in Mexico have triggered predictable questions from security analysts and the media. Will the arrests fatally weaken the CJNG? Will Mexico avoid repeating its most violent year on record? And what will the country’s criminal landscape look like in the COVID-19 era? Preliminary data and anecdotal accounts provide partial answers. They suggest an embattled CJNG will maintain pole position in a rapidly evolving but still brutally violent criminal economy.

The CJNG is what management consultants might call a family-influenced business, and it is because of this trait that recent arrests targeting the group will likely have limited effect. The family that sits atop the cartel, the Osegueras and their in-laws, the González clan, allegedly oversee an enterprise with operations across the Americas, Europe, and Asia and revenue streams including drug trafficking, oil theft, extortion, and counterfeit goods. The extended family provides continuity of leadership for those operations – blood or marital ties commonly link the CJNG’s senior leaders with their lieutenants – and “influences” the cartel’s trajectory with its decisions. However, the family relies on a deep bench of external hires to manage daily operations, such as heroin production, which reached an estimated 106 metric tons in 2018, according to a DEA official quoted by Reuters.

That structure helps to mitigate key person risk, where the loss of a senior figure like Rubén Oseguera González, reportedly the cartel’s second-in-command at the time of his arrest, could materially diminish operational effectiveness. Indeed, the CJNG lost multiple González family members to arrest between 2015 and 2017, including those that laundered cartel money and financed the CJNG’s rise in 2010. The cartel also weathered at least two internal splits in the last three years, with operational cells calling themselves the Cártel Nueva Plaza and Los Cabos breaking away in Jalisco and Baja California states, respectively. Yet, none of those losses materially slowed the CJNG’s growth, suggesting resilience in the face of the latest arrests is the most likely outcome.

The CJNG’s severed supply chain poses a more material operational risk. The cartel imports industrial quantities of precursor chemicals from China through at least four of Mexico’s maritime ports, with an August 2019 seizure of 23 tons of fentanyl precursor chemicals suggestive of the scale of the operation. Similar supply disruptions, this time from Chinese COVID-19 restrictions, will drive up the price of the cartel’s synthetic drugs over the short term. Indeed, one Mexican trafficker told Vice in mid-March that prices for a pound of methamphetamine in Mexico have already more than doubled. If prolonged, such increases could cause the CJNG’s wholesale buyers to look elsewhere for more competitive pricing. A partial closure of the US-Mexico border, which limits access to the CJNG’s most important synthetic drug market, will only compound the problem.

To compensate, the CJNG will likely try to double down on revenue streams within Mexico. Increasing its share of the retail drug market will undoubtedly be a priority, as will continued extortion of commerce in territory it controls, but these objectives will have to wait until most local businesses re-open. Meanwhile, the cartel may try to profit from the pandemic by targeting the health sector. Mexican press reports, citing Attorney General’s Office information, suggest the CJNG distributes stolen and counterfeit pharmaceuticals and forces small and medium-sized pharmacies in Jalisco, Guanajuato, Guerrero, and Michoacán to sell them.

As the CJNG emphasizes domestic revenue, it will come into zero sum competition for territory, resources, and customers with other groups also facing constraints on logistics and supply. That competition will only exacerbate pre-existing conflicts, such as the war the CJNG has waged against the Santa Rosa de Lima cartel for control of oil theft in Guanajuato state since 2017. Such CJNG offensives against rival groups were a significant driver of Mexico’s more than 34,500 murders in 2019.

Mexican government data suggests 2020 will remain just as violent, and the CJNG just as active, despite COVID-19 restrictive measures. During the week of 23-29 February, when Mexico recorded its first COVID-19 case, there were 543 murders nationwide at an average of 77 per day, according to Mexico’s Security Secretariat. Despite social distancing measures, the following month still proved to be the most violent on record since the Mexican government began collecting homicide data in 1997. The country logged 2,585 murders at an average of 83 per day during March. Notably, roughly a quarter of those killings occurred in Guanajuato, where the CJNG continues to fight for control of oil theft, and in Mexico State, where it competes for the retail drug market with family-run criminal cells and splinter groups of once prominent cartels.

With security funding to combat the violence in Mexico being diverted to the pandemic response, Washington sees an opening to put added pressure on the CJNG and its rivals and further weaken cartels it perceives as vulnerable. The White House announced on 1 April the deployment of additional Defense Department resources to the Caribbean to interdict drug shipments. Meanwhile, a surge in extraditions of Mexican crime figures to the US that began in December looks likely to continue, with Mexican cooperation motivated by Washington’s November 2019 threat to designate cartels as terror groups.

For the Oseguera González family, this means more difficult months ahead, with challenges to be faced in business, in court, and on the streets. But for a family that is believed to have been in the drug business for decades, pressure is nothing new. And if history is any guide, the CJNG will come out fighting.

Andrew Rennemo works at an international financial institution. He has held roles in U.S. government focused on transnational threats and as a management consultant for PwC focused on risk and compliance and forensic investigation in Mexico.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any institutions with which the authors are associated.