Summary

If the Indian government has in fact pulled out of the long-stalled Iran-Pakistan-India (IPI) natural gas pipeline, an energy-hungry China may prove ready and willing to supplant New Delhi’s role in the project.

Analysis

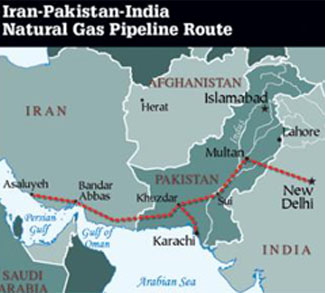

The 2,700 kilometer pipeline originally sought to transport natural gas from Iran’s South Pars field through Pakistan and into the thirsty Indian market. At every turn, the IPI pipeline has had to compete with the U.S.-championed Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline that has hitherto been thwarted by the resilience of the Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan.

Since the IPI pipeline‘s inception, the Indian government has had to carefully balance energy considerations with the project’s many potential strategic drawbacks. In the end, it’s more likely that New Delhi will choose to nurture the nascent U.S.-Indian strategic engagement and pull out of the project. India’s decision will no doubt be made easier by Iran’s hard bargaining on gas prices, recent energy discoveries within India, and New Delhi’s reluctance to allow Pakistan any strategic levers in the wake of the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks.

In what is becoming a re-occurring theme in the regional competition between these two BRIC countries, India’s withdrawal from the project could open a door for China. Politicians in New Delhi will be watching intently to see if Beijing swoops up yet another energy prize, and in doing so deepens the Chinese strategic encirclement of India.

The IPI pipeline poses several possible risks and rewards for the Chinese government. With India out of play, Iran has less leverage to drive a hard bargain on gas prices, and a new over-land energy link would help further China’s energy diversification strategy. However, the project faces several political and logistical difficulties that could scuttle Chinese participation.

The pipeline’s path is set to traverse some very difficult terrain in Pakistan’s Gilgit region, increasing the costs and time required to eventually connect to Xinjiang. Moreover, the massive investment required to link China would be imperiled in the event of an American attack on Iran or mass civil upheaval in Pakistan. Given the geopolitics and the harsh terrain involved, Beijing might just be feigning interest in the IPI pipeline to get a better deal in negotiations with Russia on relatively safer Siberia-China gas pipelines.

If China does become a full partner in the IPI pipeline, however, it will provide another opportunity to build on Beijing’s string of pearls. Chinese officials have made public their desire to turn the Chinese-built Pakistani port of Gwadar into an energy hub. A link to the IPI pipeline, and over-land transport links in the form of the Karakoram Highway represent substantial Chinese interests in Pakistan. As such, Sino-Pakistani collaborations to build naval facilities and oil refineries at Gwadar are being interpreted by Washington and New Delhi as a prelude to the establishment of a Chinese naval base there. Whether this is true or not, if China joins the IPI project, then the odds of China supporting American efforts to isolate Iran would effectively be reduced to zero.

A string of threats and complaints emanating from Washington have fallen on deaf ears in Pakistan, a country that will be suffering energy shortages as soon as 2012 if new sources are not found. U.S. officials have gone so far as to hint that U.S. aid to Pakistan will be affected if Islamabad goes ahead with the IPI pipeline. For Pakistan, threats of lowered financial assistance pale in comparison to the threat that energy shortfalls could pose to an already beleaguered Pakistani government.

American diplomats have not been able to scuttle the IPI project and push through their favored TAPI pipeline, an indication of American decline in the region. States like China, India and Russia are not only increasingly viable alternatives to provide aid, technology, and investment in the region, but are also willing to do business with anyone.