As China continues to increase its strategic footprint in the Central Asian region, Mackinder’s Heartland theory resonates quite significantly. China aims to develop its power projection capabilities by deepening its influence in Central Asia. If it remains uncontested and unbalanced-against, the Northeast Asian state may continue treading closer towards its hegemonic ambitions. India must thus play a formidable role in reviving its Connect Central Asia Policy to check China’s growing strategic interests in the region. India has often been on the receiving end of China’s assertiveness in the Indian Ocean. In order to deter future aggressive actions from Beijing in its geographical neighborhood, India must forge stronger relations with China’s neighbors.

The Heartland Theory and Central Asia

In 1904, Sir Halford Mackinder provided the foundations for the concept of land power in geopolitics through his pioneering work, The Geographical Pivot of History. He focused on issues of global strategy and the balance of power between states. Mackinder noted that, while only a quarter of the world’s surface was land, the three contiguous continents of Asia, Europe, and Africa constituted two-thirds of the planet’s solid surface. He referred to this landmass as the World Island. The World Island is a crucial geographical space because it is believed that whoever would gain exclusive control of this region will have the capability to control the rest of the world.

Mackinder, however, stressed that this relied on the developments of the closed region of Eurasia, which was named as the pivot of the world’s politics. In 1919 however, Mackinder’s work, The Democratic Ideals and Reality, proposed extensions to the scope of his ‘pivot area’ of 1904 and renamed it the Heartland. The Heartland geographically includes the part of Eurasia that is formed by Central Asia, the Caucasus, and parts of present-day Russia. Strategic domination thus involves the control of the Heartland and exclusive access to energy resources in that region. Mackinder summarizes this with his famous statement, “Whoever rules East Europe commands the Heartland; whoever rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; whoever rules the World-Island commands the World.”

Present-day Central Asia emerged as an independent geographical region after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Looking into the theory of the Heartland and the maps presented by Mackinder, the Central Asian region clearly lies in the center, or the ‘heart,’ of the Heartland. In all the models of the Heartland illustrated by Mackinder in 1904, 1919 and 1943, the region establishes itself clearly as such. This shows the strategic importance of Central Asia in the Heartland thesis of Mackinder; additionally, it also provides a clear picture that to strategically dominate international affairs, access and influence over the Central Asian region is necessary.

Why Central Asia? A Geopolitical Evaluation

Central Asia is an important part of the world´s political and economic system, being surrounded by some of the most dynamic economies in the world; among them, three are from the BRICS countries (Russia, India, and China). Central Asia has served as the crossroads for Eurasia for centuries. In fact, the Central Asian region can be considered an intersection point between the West and the East. As a result, foreign powers have tried relentlessly to gain exclusive access to the region to project power and dominance. As Xiaojie Xu notes, “the civilizations that dominate the region have been able to exert their influence in other parts of the world.” It must be noted, however, that the survival of the Central Asian states significantly relies on the maintenance of several corridors and logistical nexuses. These corridors are highly strategic as they connect and extend towards China, Russia, Europe, the Caucasus region, and the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). Central Asia is geopolitically placed with China to the East, Europe to the West, Russia to the North and states like India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Turkey to the South.

In terms of its energy capacity, Central Asia is a crucial region for major energy consumers because of its rich oil and gas resources. Known as the “second Middle East” or the “second Persian Gulf,” Central Asia has 16 major sedimentary basins, including 10 basins producing oil and gas that are mainly distributed in the three countries bordering the Caspian Sea; namely, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, which occupy an important place in terms of the world’s supply of oil and gas.

Central Asian oil and gas resources are increasingly concentrated in the west, particularly in the western region of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, where oil and gas account for 95.7% and 99.3% respectively of the total resources and proven reserves account for almost 100%. Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan in the east are relatively poor in oil and gas resources. Among the three states, oil resources are prevalent in the north, while gas resources are increasingly concentrated in the south. Kazakhstan in the north has rich and abundant oil reserves, but is relatively low in gas reserves; however, Turkmenistan in the south is rich in gas reserves, but poor in its oil reserves.

By the end of 2017, Kazakhstan had a total reserve of 1.1 trillion cubic meters of natural gas. Turkmenistan had a total reserve of 19.5 trillion cubic meters of natural gas. Uzbekistan had a total reserve of 1.1 trillion cubic meters of natural gas. By the end of 2018, Kazakhstan had a total proven reserve of 30 x 10⁹ barrels of oil. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan both had a total reserve of 0.6 x 10⁹ barrels of oil. In terms of production, Kazakhstan produces 1.9 million barrels of oil daily. As of 2018, Kazakhstan produced 91.2 million tons of oil, Turkmenistan produced 10.6 million tons of oil, and Uzbekistan produced 2.9 million tons of oil.

China’s Presence in Central Asia

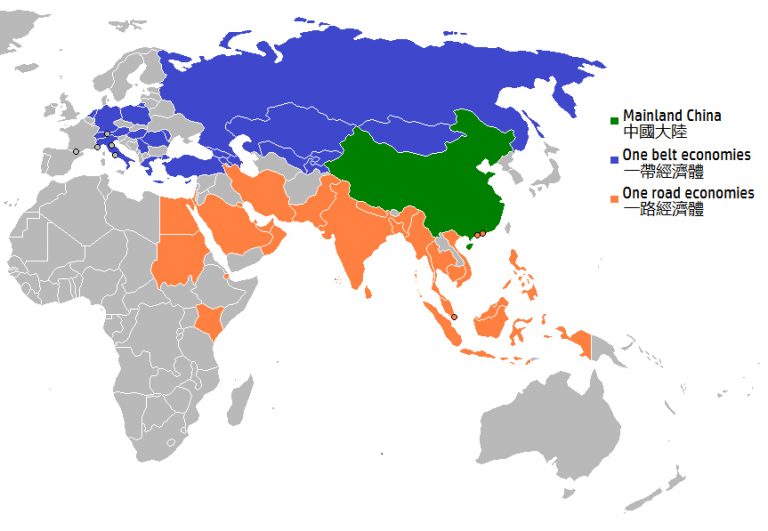

China continues to deepen its influence and engagements with the Central Asian Republics (CAR) – Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan – under the banner of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI allows China to steadily increase its investments in many states. Moreover, Beijing seeks to set global regulatory standards that will bestow advantages to Chinese enterprises and undermine the principles of free trade. China has intricately selected investment targets that are viewed as politically profitable inroads into Europe.

As of 2017, China had invested a total of US$304.9 billion worth of contracts with its partners in the Central Asian region, in sectors that include transport, communication, energy infrastructure, financial linkages, technology transfer and trade facilitation. Moreover, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan have also received loans from China as well as surveillance technology for security and policing, particularly from Chinese tech giant Huawei. This is China’s way to involve itself significantly in the affairs of the Central Asian region and to increase its political clout in the geographic space.

China has also been improving its position in the region through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). The SCO, commonly termed as the alliance of the East, has allowed Beijing to engage in the political and security affairs of the region. In fact, China is steadily increasing its strategic footprint in Central Asia and closing the gap with Russia. This implies that Moscow’s influence can be significantly undermined in the coming years. Beijing is muscling in on the former Soviet republics through increased arms sales, training programs, and new military outposts.

In sum, China has been consistently making its presence felt in Central Asia because of the latter’s geopolitical significance in Beijing’s great power calculations. Bearing Mackinder’s theory in mind, if Chinese power and influence remains uncontested in the region, Beijing may achieve the capability to project power beyond the World Island.

India’s Connect Central Asia Policy: In Need of Reformation

India has recognized that it must enhance its footprint in the region as well, not necessarily to “command the Heartland,” but to deter China from doing so. The ‘Connect Central Asia’ policy (CCAP) was first unveiled by India’s Minister of State for External Affairs, E. Ahmed, in a keynote address at the first meeting of the India-Central Asia Dialogue, a Track II initiative, organized in June 2012 in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan to fast-track India’s relations with the CAR. The policy calls for setting up universities, hospitals, information technology centers, an e-network in telemedicine connecting India to the CARs, joint commercial ventures, improved air connectivity to boost trade and tourism, joint scientific research, and strategic partnerships in defense and security affairs. During SM Krishna’s visit to Tajikistan in July 2012, the former foreign minister expounded the unfolding policy under the rubric of “commerce, connectivity, consular and community.”

The betterment of trade and commerce between India and the region would not be solely in the arena of pure economics, but would also enter the domain of geoeconomics. This is because Central Asia is strategically positioned as an access point between Europe and Asia, and offers extensive potential for trade, investment, and growth. Since the region is richly endowed with commodities such as crude oil, natural gas, cotton, gold, copper, aluminum, and iron, the region has generated new rivalries among external powers.

Geoeconomics is intimately linked with geopolitics and therefore economic cooperation between India and the CAR plays an important role in developing strong defense ties by enhancing strategic and security cooperation with a strong focus on military training. Security cooperation between India and the CAR also includes conducting joint research on military-defense issues, coordinating on counterterrorism measures, and a special focus on consulting closely on the issue of Afghanistan, whose security is extremely crucial for both parties. Despite these initiatives, however, India’s engagements with the CAR remain relatively low. The need to bolster relations is crucial at a time when China seeks to pursue hegemonic ambitions.

A Way Forward for India

Despite China’s increasing trade and investments with the CAR, many feel that doing business with Beijing involves its own subtle costs. Moreover, fault lines are starting to form in China’s relationship with the CAR with respect to issues of transparency and accountability. China’s easy terms for lending money comes at the cost of the encroachment of Chinese business and politics as well as the erosion of the CAR’s ownership of its natural resources. Out of the 68 countries that have agreed to Chinese investments under BRI, 23 face the risk of landing in China’s debt trap. In the case of the CARs, the less resource-rich countries such as Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan already owe China an estimated US$ 4 billion and US$ 1.38 billion in loans, respectively. China owns 41% of Kyrgyzstan’s debt and 53% of Tajikistan’s debt. Furthermore, Tajikistan and China have had an ongoing conflict over the border; but to skirt debt repayments, Tajikistan has handed over a significant amount of border control.

As a result, the CARs are looking to new partners in an effort to balance China’s growing presence in the region. India can play a formidable role in balancing Beijing in the Central Asian region considering the former’s cordial and historic relations with the CARs. However, India would have to significantly revive and enhance its CCAP to guarantee its commitment to make these stronger ties a reality.