The nature of human work is undergoing a fundamental shift driven by the forces of automation and globalization, particularly in the field of manufacturing. This shift is not only changing the US workforce; it’s altering the socioeconomic fabric of the country, sometimes with stark political ramifications. How should US policymakers respond to these historic trends?

We sit down with Edward Alden of the Council on Foreign Relations to discuss the future of employment and the US economy. Our conversation builds on a new report co-authored by Mr. Alden, “The Work Ahead.”

Rising inequality in wage earnings has been a trend in the developing world since 1979, but it’s particularly pronounced in the United States. What accounts for this?

There are several explanations which probably add up to a broader conclusion:

The U.S. social safety net is quite weak, so employees who lose their jobs fall harder and farther than in most other advanced economies.

The United States has little commitment to mid-career retraining, which means that many who lose their jobs end up returning to much lower-wage work.

The United States is particularly successful in sectors that provide great rewards to the most highly educated and ambitious workers, especially financial services and technology/media.

Unions in the United States have seen a much steeper decline in membership and influence than in most other advanced economies. One of the reasons the United States became a more equal society up through the 1970s was the influence of labor unions, and that has all but disappeared.

Automation is one of the major forces changing the nature of employment. Regarding its impact, The Work Ahead states: “Whether these [new] technologies will destroy more jobs than they create is impossible to know with any certainty.” What is one piece of evidence to support the pessimistic view that job termination resulting from automation and AI will come to exceed job creation in new fields by a large margin?

The most widely-cited study for large-scale job replacement was done by Frey and Osborne at Oxford University. It suggested that as much as 47 percent is “at risk” of automation over the next two decades.” If true, that would be a level of job displacement that would be very difficult to replace in any sort of timely fashion.

… And one piece of evidence to support the more optimistic view that job termination will be largely offset by the creation of jobs in entirely new fields?

The more optimistic scenarios, such as that developed by McKinsey suggest that while up to 30 percent of jobs have at least some tasks that can be automated, far fewer face complete elimination. In general, the adoption of new technology is far slower than the capability, due to regulatory and consumer resistance. The rollout of self-driving cars, for example, is likely to be slowed by public concerns over safety and security.

The question of how many jobs will arise to replace those lost is basically an extrapolation from economic history. In the past, despite technological disruption, new jobs have always emerged to replace those that are lost. Technology improves productivity, which makes us wealthier, and that money is inevitably spent on services and goods that create new jobs for other people. There is no particular reason to believe that this will not continue to be true in the future.

The Work Ahead points out that concerns over technological disruption are nothing new, citing John Maynard Keynes’ warning of widespread unemployment as far back as 1931. What, if anything, about this latest wave of technological change suggests that it might differ from past examples?

The main difference, and we simply don’t know exactly how significant this will be, is that earlier technological disruption largely replaced manual labor with machine labor. The current and coming waves of disruption can and will replace many forms of cognitive and intellectual work. The line between what machines can and cannot do is becoming much blurrier. This could result in a larger labor market impact than we saw in previous waves of disruption.

Is there a country in the developed world that stands out as a positive example of preparing its workforce for the trends outlined in The Work Ahead, particularly with regards to adapting to technological change?

The most effective models are ones that embrace both “work/learn” opportunities for younger students, and lifelong learning for mid-career workers. The European apprentice models, especially Switzerland and to a growing extent Germany, do the first part of this quite well. One of the great virtues of the Swiss model is that it is not a “tracking system.” Almost all high school students do apprenticeships of some sort, and while some go directly into the job market many others go on to higher education, including university degrees and beyond. No country has yet developed the ideal approach for lifelong learning. Singapore is experimenting with educational subsidies for mid-career workers. And many companies (including U.S. companies like AT&T) are doing this quite well on their own. But it is still a work in progress.

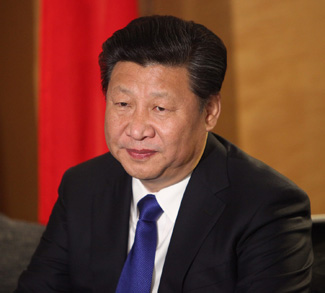

One of the recommendations of The Work Ahead is to prevent forced technology transfers, a problem that is particularly acute with regards to China. Is President Trump doing a good job in this regard, and if not, what else should he be doing?

Maintaining U.S. technological leadership will require a comprehensive approach, similar to the effort in the 1980s to meet the challenge of Japanese economic competition. That includes investing in research & development, encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship, and expanding high-skilled immigration. The United States also needs to protect its intellectual property and discourage companies from sharing their best innovations with competitors. On China, this is a problem that the United States shares with Germany, Japan, the UK and many other countries. The better approach would be a coordinated effort among these countries to increase pressure on China and to discourage their own companies from entering into tech transfer arrangements that could do long-term damage to economic competitiveness.

Of all the potential policy solutions that the US government could adopt to better prepare workers for the future, which do you think takes precedent as the most important?

The most important challenge is linking education more closely to economic opportunity. That will require: closer collaboration between employers and educational institutions; far more apprenticeship/internship/work experience opportunities for students to better prepare them for employment opportunities; robust outcomes data to allow students to better assess the costs and benefits of different educational choices; and the reform of hiring practices to open more opportunities for those without four-year college degrees. This effort will require action at all levels – federal and state governments, employers, educational institutions and non-profits.

Do you think that the challenges arising from new realities in the workforce are receiving enough attention in the political sphere? If not, how can we draw more attention to the problem?

There is a big disconnect between growing awareness of workforce challenges and the so far limited response from the political sphere. There are many promising state and local initiatives, but they are generally small and under-funded. The federal government, which has the most resources, is doing the least. Both Congress and the administration are at best seeking small tweaks to existing programs, such as apprenticeships, and it is not clear that even these will come to fruition. Changing this equation will require sustained attention and pressure from many different segments of society.

What is fueling regional economic disparities in the United States and what can be done to help alleviate them?

The short explanation is that the loss of manufacturing jobs – which was especially pronounced in the 2000s as a result of import competition and technology – had very unequal impacts around the country. There were many large town and smaller cities where one or two factories were the anchor of the local economy, and their disappearance could not be overcome. At the same time, the large cities that concentrated highly-educated workers have seen outsized gains from the growing knowledge economy. These trends have propelled some places ahead and left others behind.

Is there a specific regional initiative that stands out as a positive example of bringing about economic rejuvenation in a distressed community?

I am going to defer to some of my Brookings colleagues on this one, especially this paper.

How can the United States reform its immigration system to make it more fit for purpose in a rapidly changing global economy?

The Congress has tried several times to no avail sadly. The two top priorities should be opening the door to more highly skilled and educated migrants (taking advantage in particular of the magnet provided by American universities) and resolving the status of the roughly 11 million unauthorized migrants to allow them to participate fully in the economy.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.