Turkey’s war against Islamic State began with bombs being dropped on Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) forces – a central actor in the ongoing insurgency across parts of Syria (a country that ostensibly no longer exists) and Iraq. The PKK has sought autonomy from Turkey since the mid-1980s, with tens of thousands of Turkish and Kurdish soldiers and civilians being counted as part of the casualties of the roughly 30-year conflict. Attempts to carve out a sovereign Kurdish homeland from Turkey during the 1980s led to the deaths of over 30,000 people, many of whom were ethnic Kurds. As part of Turkey’s new role in its conflict with ISIS, the United States has been granted permission to launch aircraft from the Incirlik airbase located near Adana. The United States already has approximately six fighter aircraft and several hundred military personnel stationed at the base.

The battle of Kobane, which lasted from mid-September 2014 until mid-March 2015, brought the fighting to the borders of Turkey. At the end of July 2015, when Turkey entered into the conflict, its attacks against the PKK were the first strikes against the Kurds situated in northern Iraq since the brokering of a peace deal between Turkey and the PKK in 2013. The Kurdish group’s accusations that the Turkish government is plotting terrorist attacks (in collusion with ISIS forces) against ethnic Kurdish communities greatly adds to tensions due to Ankara’s already inimical disposition toward the Kurds.

The situation in northern Iraq and Syria is a Gordian knot: Turkey vs. Kurds (with Kurdish intergroup fighting predating ISIS) vs. ISIS (with internal fragmentation and al-Qaeda support) vs. Syrian opposition groups.

Turkey’s engagement with the Kurds does not resemble an even distribution of force. First, Ankara is battling the Turkish Kurds – the PKK that operates in northern Iraq and Syria (also in northern Syria) and that is struggling for autonomy. Second, Ankara is also antagonistic towards, though not fighting, the Syrian Kurds – the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and the People’s Protection Units (YPG). Third, Ankara supports the Iraqi Kurds – the KRG (Kurdistan Regional Government), Peshmerga (the military forces of the KRG), the KDP (the dominant Iraqi Kurdish party), and the PUK (the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. Fourth, all of these Kurdish groups are fighting ISIS, which Turkey is also fighting. Not all of the Kurdish groups are at peace with one another. The PYD and Kurdish National Council are rivals, so are the PUK and the KDP. As part of this mix, Syrian opposition groups have displayed both strategic and tactical value on the battlefield for Western forces. During the course of the fighting, Ankara is indirectly (and in several cases, inadvertently) supporting the military efforts of the Kurds.

Is Turkey providing a platform for the emergence of an independent Kurdish state?

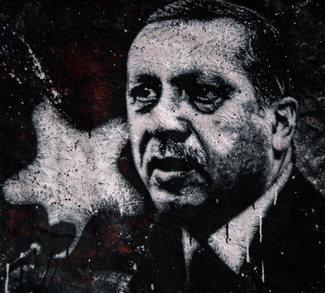

It might be that the prospect of an independent Kurdish state is unrealistic and that Turkey prefers the existence of ISIS forces south of its borders. Recep Tayyip Erdogan has adopted a very harsh tone toward the idea of Kurdish sovereignty, vowing to block the creation of such a state. “I am addressing the whole world,” and that, according to Erdogan, “[w]e would never allow a state to be formed in northern Syria, south of our border.” Despite Kurdish efforts at democracy, they remain subordinate to Arab domination and authoritarianism. Western media outlets are increasingly lending sympathy to the Kurds’ struggle but not necessarily to the idea of an independent Kurdish state in the Middle East – a scenario that would have to involve the dismemberment of four states: Turkey, Syria, Iran, and Iraq. Kurdish self-determination would have to be carved out of these existing sovereign states.

Westerners subscribe to the idea that the Kurds either stand as a force for good or are fighting for a good cause, with people from the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the Netherlands (among other countries) traveling to the Middle East to lend their support by fighting alongside Kurdish troops. Western governments have not wholly opposed these efforts. According to the Home Office, “UK law makes provisions to deal with different conflicts in different ways – fighting in a foreign war is not automatically an offence but will depend on the nature of the conflict and the individual’s own activities.”

This is a narrow shift, but one deserving of close observation, in the tendency of Western attitudes towards the fate of the Kurds. The West and Westerners are certainly paying attention much more than they used to. However, a major misrepresentation in Western media discourse now is that an independent Kurdistan would be the close ally of the United States and of Israel. Its creation would be a brief afterglow of many years of war in Iraq, the folly of the Arab Spring (the so-called “Fourth Wave” of democracy), the Syrian civil war, and what can aptly be typified as a still-nascent ISIS conflict in the Middle East.

The conflict involving ISIS and the West (and its friends and allies), that has strained the relationship shared by Turkey and some Kurdish groups, has also supplied the YPG with low-to-moderate military strength (some analysts claim that the YPG has more than 15,000 recruits). The spotlight now shines on ISIS as well as other militant groups that have the potential to form their own pseudo-states. During the course of intensive fighting, the YPG has come to control a notable strip of territory along Turkey’s southern border with Syria – a country that could be divided up in the near future. Ankara, which was reluctant to join the US-led conflict against ISIS, is now part of the same conflict in which the YPG (labeled a terrorist organization by Turkey) plays a leading role. Ankara’s previous apprehension over joining in anti-ISIS efforts strained its relations with Western countries, including its NATO brethren. Turkey’s standing reluctance to fight ISIS, nonetheless, has also provided the YPG with time and space necessary to build its military strength, which in turn, leads to Kurdish political power.

Turkey has created a number of military and ideological frontlines that it will have to manage while coordinating plans with the West to push ISIS forces out of northern Syria. Ensuring that the right Syrian opposition forces fill the void will be a simultaneous constraint. Unfortunately, Ankara and the West need to factor the unreliability of groups fighting in Syria in a coordinated plan of action. Jabhat al-Nusra, a close ally of al-Qaeda, also plays a role in Turkish/Western plans to stabilize the area, given that it stands as one of the many groups in the area that is made-up of Islamists extremists, including jihadists.

Turkey’s complex relationship with various Kurdish groups and its hesitance to act in tandem with its NATO allies has cultivated extensive uncertainty and instability. The strain of choosing between ISIS and the Kurds (the biggest nation in the world that has yet to enjoy the benefit of self-determination) is growing. Turkey has stepped beyond the safe confines of its borders with what, by many accounts, would be seen as sufficient military capabilities. However, the wave of attacks that have taken place in Istanbul and Sirnak only a few weeks after Turkey took its bold stride is a symptom of a foreign policy decision that poses very systemic risks to Turkey’s internal and external security.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.