What happened?

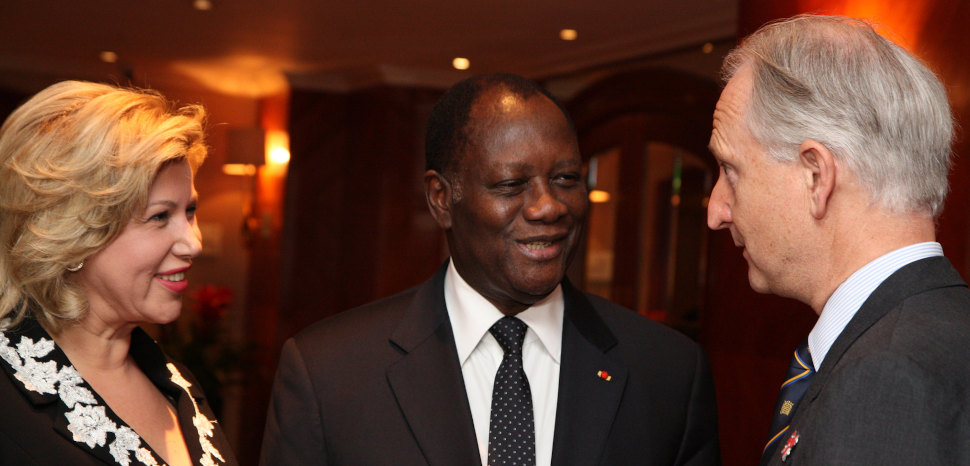

Cote d’Ivoire’s President Alassane Dramane Ouattara increased the odds of political instability when he announced in August that he was running for a controversial third term. The move comes at a time when the country’s economic forecast has been slashed due to COVID-19, and the region is experiencing a rash of leaders trying to extend their time in office – a trend called ‘third-termism’ – as well as increasing activity from violent extremists organizations.

President Ouattara’s plans to peacefully transition power for the first time in the country’s history were upended when his chosen successor, Prime Minister Amadou Gon Coulibaly, died just three months before the next election, and the alternate candidate, Defense Minister Hamed Bakayoko, was linked to a drug trafficking scheme. Senior officials in the Rassemblement des Houphouëtistes pour la Démocratie et la Paix (RHDP, the ruling coalition of political parties) pressured Ouattara to renege on his promise not to run again in order to fill the void left by Coulibaly. The August 8 announcement set off a wave of protests in the country that were met with violent repression and left eight people dead—underscoring how fragile the situation is in the former French colony.

In response to Ouattara’s announcement, opposition candidate and former president Henri Konan Bédié of the PDCI party asked the other opposition parties, including members from the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI, former president Laurent Gbagbo’s party) and Generations and People in Solidarity (GPS, former rebel leader Guillame Soro’s party), both of whom are barred from the election, to stand against Ouattara. He also called for wider public protests. The opposition has demanded nationwide reforms in exchange for their continued participation in the election. Their reform demands include Ouattara’s withdrawal from the ballot; the dissolution of the constitutional council; the dissolution of the electoral commission; and reform of the entire election framework. The move has essentially deadlocked the electoral process.

Why does it matter?

Political factors

Ouattara is abandoning democratic norms by appearing to tamper with the election.

The Constitutional Council, most of whom are appointed by the president, not only allowed the dubious third term run but also approved only 3 candidates out of 44 applicants to stand against the incumbent:

- Former President Henri Konan Bedie (PDCI) – a former Ouattara ally in the past two elections. The alliance fell apart in 2018 when Ouattara would not commit to fielding a candidate from the PDCI camp.

- Former Prime Minister Pascal Affi N’Guessan (FPI) – assumed control of the FPI after Gbagbo was exiled. N’Guessan is a weak candidate who garnered less than 5% of the vote in 2015.

- Kouadio Konan Bertin (independent) – a former PDCI member who left after a disagreement with Bedie. He is another weak candidate who earned less than 5% of the vote in 2015.

N’Guessan and Bertin are very weak politically and have the potential to draw votes away from Bedie, the one serious contender, while not being a threat to Ouattara. Additionally, the government has excluded the very popular Gbagbo and Soro from the election for having criminal convictions against them—convictions the Ivorian government imposed.

The president argues that updating the constitution in 2016 reset his term limits, allowing him to serve until 2030. In fact, the constitution is ambiguous regarding term limits across previous versions. However, the opposition parties are firm in their disagreement. They contend Ouattara has served his two terms and should step aside. Ouattara’s maneuvering may get him re-elected but invites uncertainty about the legitimacy of the election and will incur, at best, legal challenges if he wins or, at worst, another coup.

Economic factors

Ivory Coast’s fast-growing economy has slowed due to COVID-19. Trading Economics lists 2019 GDP at just under seven percent, but in the second quarter of 2020 GDP dropped below four percent. Despite its economic strength, the country has a high poverty rate of 46 percent—indicating not everyone benefits from the strong economy. The World Bank indicates more private investment is needed for Ivory Coast to sustain its growth and make the economy more equitable. COVID-19 will continue to dampen the country’s economic growth at least through 2020. Any political instability will drag the economy down further and deter private investment.

Security factors

Africa in general and West Africa in particular is under siege by violent extremist organizations (VEO), like Islamic State and al-Qaeda regional affiliates, looking for a new base of operations after the war in Syria and Iraq pushed them from their previous operating areas. These groups repeatedly turn to Africa as a new base of operations. This is in part thanks to many of the countries’ relatively porous borders, large populations of unemployed young people, weak governments and security apparatus, and numerous ethnic divisions – all of which conspire to provide these VEOs a foothold in the societies they target.

An outpost on the northern border of Ivory Coast was recently attacked in retaliation for participating in a joint-counter-terrorism operation with Burkina Faso, in which over a dozen Ivoirian soldiers were killed or injured. Domestic conflict in Ivory Coast would provide an opportunity for more attacks and a chance for VEOs to expand operations in the country (though most Ivoirians identify more with Hezbollah than IS or al-Qaeda).

A regional precedent

Ouattara is not the only West African leader seeking a controversial third term. Leaders from Egypt, Uganda, and Comoros have all used political maneuvers to increase their terms. President Alpha Condé of Guinea also wishes to extend his stay in power by the same mechanism Ouattara is using—implementing a new constitution to reset term limits.

The African Union even has a formal declaration prohibiting such acts. The African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance “prohibits any amendment or revision of the constitution or legal instruments that constitute an infringement on the principles of democratic change of government.” But it has yet to act on it, preferring instead to use “quiet diplomacy.”

How the African Union (AU), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and the international community choose to treat Ouattara’s constitutional coup, will have repercussions across the region as other leaders look for winning strategies to extend their control.

What comes next?

The potential outcomes around the election are difficult to predict. However, the opposition already views the electoral commission (the independent body that oversees the election) as biased. They have made it plain that they believe President Ouattara’s third term bid is unconstitutional and therefore illegitimate; and they have called for public protests against his running. In fact, two electoral commissioners have already resigned in protest, calling for a delay of the election until the commission is reformed.

For its part, the Ouattara’s administration has grown increasingly authoritarian. Jessica Moody at Foreign Policy noted, “the president’s increasing tendency toward policies that contravene human rights, due process, and freedom of speech has gotten far less attention than his country’s growth and progress. Indeed, Amnesty International documented incidents of uniformed police standing by while armed, plain clothes men attacked unarmed citizens protesting Ouattara’s third term bid.

Ivory Coast has all of the necessary elements for conflict over the October election—rising inequality, corruption, high youth unemployment, ethnic tension, political resentment, repression, and three leaders’ commitment to a decades old feud that has no place in civil society.