Astana approaches Washington….

Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev met with US President Donald Trump in Washington DC on 16 January 2018, which was a major diplomatic victory for the Central Asian state. As part of the visit, the US Department of State praised bilateral ties, highlighting in a press release how trade “grew to $1.9 billion in 2016.” Additionally, the renowned think tank Atlantic Council held an event in January with the Kazakh ambassador to the U.S., H.E. Erzhan Kazykhanov, to discuss bilateral relations. The two governments have also increased military ties and there have been new initiatives related to cooperating on nuclear energy issues.

Moreover, the Kazakh government is committed to exposing its youth to the West as a Kazakh government official explained to the author that as many as 2,500 Kazakh students are currently attending universities in the United States.

….But Moscow and Beijing still exist

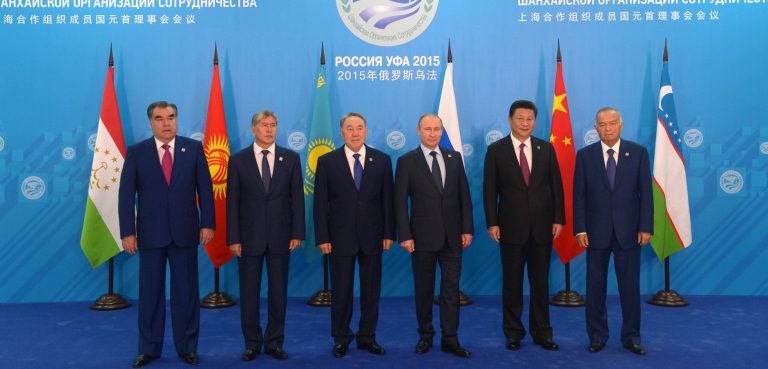

Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to assume that the Kazakh government is “pivoting” toward the West. That’s where geography kicks in. After all, the Central Asian state has a border with Russia that extends over six thousand kilometers, and also has an ethnic Russian population in the northern part of the country. Additionally, Kazakhstan is part of Moscow-backed multinational organizations, such as the Eurasian Economic Union; the Collective Security Treaty Organization; and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Due to space considerations, we cannot analyze Moscow-Astana relations in depth, but they include strong trade and defense ties (joint military exercises and Astana regularly purchases Russian military technology).

As for Sino-Kazakh relations, the two countries are both members of the aforementioned SCO and, more importantly, Kazakhstan, again, due to its geographic location, is in the middle of China’s grandiose One Belt One Road Initiative (OBOR, also known as the “New Silk Road”), which seeks to (re)connect the Asian giant with Europe through a network of roads and railways via Central Asia and Russia; and through a series of ports in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. As part of this grandiose project, a Chinese company is constructing a massive “dry port,” the Khorgos Gateway, in Kazakhstan.

Geography and Foreign Policy

The link between geography and foreign policy has been well-researched – see for example Tim Marshall’s Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the World or the works of Halford MacKinder– but we should stress that it is not solely global powers like China, Russia or the U.S., but also other nations, including regional powers like Kazakhstan, that mold their foreign policy by their geographical location in the world.

After all, it is difficult to foresee a staunch pro-Washington government in the middle of Central Asia, with Beijing and Moscow as direct neighbors. An extreme scenario was proposed in a January 2018 report by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), a think tank in Washington DC, which hypothesized reasons why Russia could militarily intervene in Kazakhstan – comparisons were made to the situation in Crimea – perhaps not by coincidence, the report was published at the same time President Nazarbayev visited Washington. Certainly, closer Washington-Astana diplomatic or military relations would be a big red flag for Moscow; though suggesting a Russian military operation in Kazakhstan seems unnecessarily alarmist. Likewise, the Kazakh government does not want to put Chinese investment at risk by supporting Washington policies that Beijing disagrees with.

Thus, the Kazakh government has to walk a fine diplomatic line regarding what it can realistically achieve at the foreign policy level, not because of lack of resources or will, but rather because of possible issues with two of its neighbors.

As a final point, it is worth noting that a January 2018 article in the New York Times noted the battle for influence between Beijing and Moscow due to OBOR, hinting at how Astana “has tried since independence in 1991 to stay on good terms with Russia but has also steadily eroded Moscow’s once overwhelmingly dominant position in the region by expanding ties with China.” Similarly, a commentary in the Huffington Post on Kazakh-Russian relations also explains why Kazakhstan cannot distance itself too much from Moscow, because doing so would risk a possible Crimea-type situation, akin to what the AEI muses, and because Russian military assistance helps President Nazarbayev’s own “anti-Islamist campaigns” at home. While the word “geography” is not flat out mentioned, it is certainly implied.

The Trump-Nazarbayev meeting was heralded as a diplomatic victory for Kazakhstan, and it will be certainly interesting to see how far bilateral relations will go. However, as this commentary has sought to explain, Kazakh foreign policy ambitions will be tempered by the country’s geographic location, namely having the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China as immediate neighbors.

In spite of the evolution of diplomacy and the metaphorical shrinking of the world due to technological advancements that facilitate faster communication and transportation, in 2018 geography continues to matter and will certainly continue to influence foreign policy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect those of any institutions with which the author is associated, nor those of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.