On Friday August 24th, an American diplomatic vehicle carrying two U.S. embassy staffers and a Mexican Navy captain was ambushed on a remote road outside of Cuernavaca, close to Mexico City. After the SUV veered off the road, three more vehicles blocked its escape route, and all four opened fire on the embassy car, wounding the two Americans on board. If anonymous “narco blogs” and other reports are to be believed, an informant with access to the Beltran Leyva cartel- perhaps with information on the whereabouts of “El H” (Hector Beltran Leyva), one of Mexico’s most sought after drug lords-may have been on board with the U.S. agents. Mexican authorities detained 12 of the “federales” that fired upon the diplomatic vehicle, and an investigation has been launched to shed light on the incident. If anonymous sources are telling the truth, then the attack could very well have been an attempted targeted assassination of the informant and the U.S. embassy staffers. The various cartels’ intelligence networks of informants- called “halcones” (hawks), who serve as “lookouts” within government agencies and rival cartels- could have alerted the relevant players in the unending cat and mouse game played south of the U.S. border.

Mexico is currently in a state of political transition. The Revolutionary Institutional Party (PRI), the old guard of Mexico’s political elite that ruled the country for over 70 years, is set to inaugurate their first president since Vicente Fox’s election in 2001, prompting U.S. policymakers to seriously consider the possibility of a strategic shift in Mexico’s war against the drug cartels. This war, which has left a death toll of close to 50,000, is not merely a national issue, and its importance transcends the sovereign frontiers of Mexico’s borders. It has vast and far-reaching national and international implications, with a hemispheric theater of operations. The case is analytically complicated by the fact that while the Mexican government is officially at war with the cartels and targets certain cartels more than others, the cartels are at war with each other, often playing the government against their rivals, producing a very interesting sub-state balance of power dynamic.

Whilst we are still not certain as to the real motive in the abovementioned attack, the incident does illustrate salient points about Mexico’s war against the narco-traffickers. The conflict offers us a fascinating case study on the evolution of sub-state criminal organizations from highly organized transporters and “exporters” of consumer products (drugs, in this case), to politically astute actors with sophisticated intelligence apparatuses funded by a multi-billion dollar trade in illegal narcotics- perhaps 20 percent of total U.S.-Mexico trade.

From Narco-Traffickers to Narco-Terrorists: The Politicization of a War

Contemporary scholarship has not dedicated enough attention to the potentially explicative causal link between Mexico’s democratic transition and its government’s decision to crack down on the drug cartels. When Vicente Fox assumed the presidency in 2001, he started the war that his successor, current out-going president Felipe Calderon later intensified. The question emerges: What prompted the Mexican government’s intense escalation in its efforts to capture or kill the cartel leaders, interdict drug shipments on a massive and unprecedented scale, and hurt the entire illegal narcotics trade? We can speculate thus. The loosening of the government’s executive strong-arm under the Fox administration impacted the relationship between the political establishment and the drug cartels, altering the balance that had kept a silent, mutually beneficial, and uneasy truce in place. The answer lies in what is undoubtedly the most important feature of any state, be it liberal, totalitarian, or even fanatical, the one factor that determines even the very survival of symbiotic relationships of corruption between government officials and sub-state criminal organizations: the asymmetrical relationship between state-actor and sub-state actor, predicated on sovereignty, that has the state actor enjoying a preponderance of the power and resources available in a given situation. Once state actors lose sovereignty to sub-state organizations, the system itself is in jeopardy, and even the corrupt symbiotic relationships are imperiled. The Mexican government was literally losing control of its own territory, functionaries, and police forces, and thus its very relevance seemed to be at stake. Consider the fact that in 2008 President Calderon discovered that his designated drug czar was actually on the payroll of the Beltran Leyva Cartel! Any rational cost-benefit analysis on the part of the Mexican government would have sided with the decision to go to war to preserve their sovereignty and power-base. Add to this the necessary pressure that the U.S. has logically placed on the Mexican government to save that massive country- which shares with the U.S. the most transited border in the world- from state failure.

If political and “existential” logic has forced the Mexican government into action, that same “realist” logic has demanded a reaction from the cartels. Since 2006 there has been a massive increase in the intensity of the violence, a violence that has carried with it the political calculation of terrorism: namely, politically and aesthetically grand violence perpetrated against civilians, including children, meant to intimidate the population and thus pressure the politicians to effect a truce with the cartels or “change the strategic focus” of the operations into functional impotence. Whilst the various cartels operate differently and even have divergent operational ideologies that govern the manner of trying to influence public opinion, the prevalent feature currently in motion is the use of low intensity terrorism, such as the gruesome executions of journalists with notes calling for media self-censorship, public decapitations and threats against schools, and mass and apparently random public shootings. Political terrorism must be grand in its scale and cool in its logic. It must reduce the political space into a clear “yes” or “no” to the political question perceived as causing the violence. It has proven somewhat effective, since the leftist candidate Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador in the recent election won second place after endlessly haranguing the vast crowds with appealing rhetorical flourishes such as “abrazos, no balazos” (hugs, not shots), and openly blaming the two dominant parties for the violence.

We must add the idolization of drug lords in certain sectors of Mexican popular culture to the range of favorable “coverage” they receive, and thus as a factor that can make a more complacent political solution more palatable to the general public. The so-called “narco corridos” (narco-ballads) either celebrate or criticize certain cartels or leaders, and many musicians have been brutally murdered as a result. Narco paraphernalia has proliferated, and in many ways the cartel leaders receive the admiration of certain youths from all social classes. In some historical epochs it has been rampaging peasant revolutionaries sporting some type of “revolutionary chic”- now it’s the image of the “narco.”

The idolization of drug lords is fueled also by popular anecdotes that illustrate personalities with charismatic appeal. It is widely reported that Joaquin Guzman Loera, alias “El Chapo Guzman,” the most sought after man in Mexico and estimated by Forbes magazine to have a personal fortune of one billion U.S. dollars, occasionally visits restaurants, posts sentinels preventing anyone from leaving, personally greets all the people in the restaurant, and pays everyone’s bill. The traditional Mexican distrust of government, and the perception that the government had violated the previous truce that allowed everyone to “be normal” has led major segments of popular opinion to call for a change in strategy.

A Potential Shift in Tactics, Though Not in Strategy

It is clear that the Mexican government’s fundamental reason for going to war against the cartels was to preserve its very legitimacy and relevance, and so it is very doubtful that the new government will change course. Sovereignty and state control, ironically, are the very elements that permit corrupt symbiotic relationships, and so the gaining of power over the cartels is paramount. The President-elect has, however, indicated an important tactical change that he will seek to implement, a change that could radically alter the manner in which anti-narcotics operations are conducted by the Mexican government.

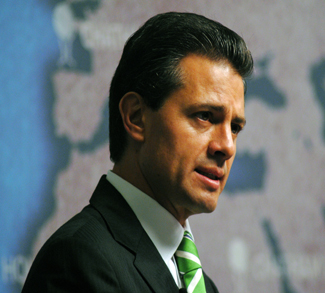

Enrique Peña Nieto has announced his intention of creating a militarized police force, a gendarmerie that would be comprised of some 40,000 paramilitary agents. The policy proposal is seemingly in response to accusations of human rights abuses allegedly perpetrated by the military forces deployed to combat the powerful cartels, which by far outgun the regular federal police forces. Facing such a proposal is one obvious question, the very issue that has made the federal police force almost completely inept as an organized crime-combating institution: How to shield the proposed force from the omnipresent “mordida”- the bribe that has allowed various cartels to use police forces against fellow rival cartels, and that has ensured virtual impunity in many areas. Indeed, along with the necessity of bearing greater firepower than the cartels, the government has made extensive use of the military for anti-narcotics missions because as an institution, the military, with its strict chain of command and hierarchically delineated operations, is much less penetrable than the police. In the case of Mexico, the Navy is the least corrupt of the branches of the armed forces, and so they bear the brunt of anti-narcotics responsibilities in the most perilous hot spots in the country. The Colombian Carabineros– perhaps the most experienced militarized police force in Latin America deployed against drug traffickers- has been actively exerting influence in Mexican policy circles, and it is likely that the proposed force would mirror its Colombian counterpart. That being said, nothing assures that the new force would be clean of corruption, and it is this very concern that may imperil the proposal if and when it comes before the divided Congress.

At a Crossroads?

For the reasons we have explained, namely, the crucial issue of governmental sovereignty, including the monopoly of the use of force, it seems most unlikely that the incoming government will change the strategic course of the Mexican government’s war against the narco-traffickers/terrorists. Even the most corrupt politicians need to hold a preponderance of available power in order to maximize any profit derived from corruption. Regardless of the party in government, the logic of maintaining power remains the same, and nothing indicates that the Mexican government is irrational. But the cartels aren’t irrational either, and they have proven themselves highly adaptable to new circumstances in the seemingly endless balance-of-power dynamic played by the government against the cartels, and by the cartels against rival cartels. The tactical use of violence against civilians as a means of pressuring the public to in turn pressure the politicians has yielded results, but the sovereignty imperative overrides even rhetorical concessions on changing to a course less motivated by capturing or killing the cartel leaders, and instead on “reducing violence.” The President-elect’s proposal to create a civilian paramilitary police force is perhaps a response to the politically dangerous policy of keeping the country as highly militarized as it is now. Such a “concession” may allow politicians to continue the unpopular war against the cartels by psychologically and aesthetically “toning down” the country’s militarization. As the matter stands now, the military will continue its counter-narcotics role for the foreseeable future, and there appears to be no real end in sight for the conflict, since both the cartels and the government have a “rational” incentive to fight. And fight they will.