The study of power politics has often centered on the activities of great powers; however, this paper argues that middle powers can also be game-changers based on their geopolitical features. As the United States (U.S.) and China continue their battle for influence in the Indo-Pacific, the Philippines can play a critical role in the overall power equation.

The following sections seek to substantiate this claim by discussing the concept of middle powers in the international system and how it can be applied to the Philippines, identifying the geopolitical properties of the Philippines, understanding the importance of the Philippines in the power equations of both the U.S. and China, and highlighting the future trajectory of the Philippines as an important middle power.

Middle Powers in the International System

The concept of a middle power has often been marginalized, if not overlooked, in great power struggle in the international system. According to Allan Patience, the definition of a middle power is vague due to the lack of attention given in the literature. However, Patience suggested three ways to classify middle powers:

First, there are dependent middle powers that are “treated warily by partners and contenders alike because of their alliances with great powers.” This kind of middle power will likely align its policies to its allied great powers with respect to signed treaties, thus softening its sovereignty in terms of military doctrine and defense industries. Second, there are regional middle powers that lack substantial influence outside a regional arrangement, but are considered important and relevant within it. Third, there are middle powers as “global citizens.” These are states that pose little or no military threat to neighbors and their respective regions but have a leadership influence in regional and international settings, as reflected by optimum domestic performance.

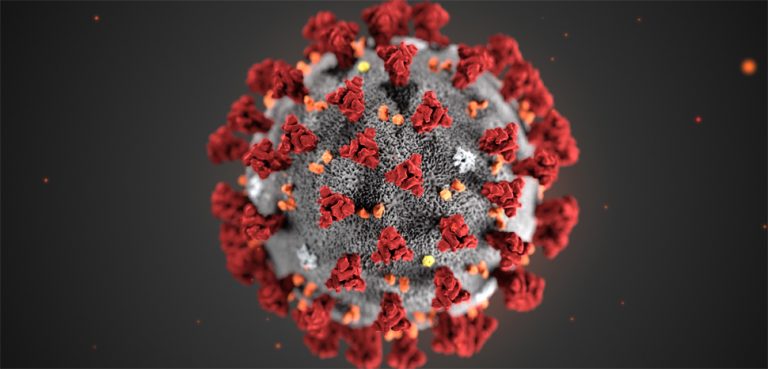

In arguing for the Philippine case, these three descriptions provided by Patience confirms its status as a middle power. In a world ravaged by a global pandemic, in addition to the growing uncertainty of great power politics, the Philippines can provide a path forward in explaining developments in the international system.

The Philippines as a Middle Power

The Philippines currently holds a middle power status in Asia. According to the Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index 2019, the Southeast Asian state ranks 17th among other states in the region; however, the Philippines ranks the lowest middle power, after North Korea. In this context, the Lowy Institute operationalized eight indicators of power, namely, economic resources, military capability, institutional resilience, future resources, diplomatic influence, economic relationships, defense networks, and cultural influence. The Philippines ranks low in terms of military capability and institutional resilience; however, the remaining indicators can be applied to the Philippines. Hence, this proves that the Philippines is a middle power.

The low credibility of the Philippines’ institutional resilience and military capability can be traced back to history. During the post-Martial Law period, the heralded fifth Republic of the Philippines in 1987 saw the erosion of its institutions marked by several coups, nationwide electric and water shortages, a devastated economy, agrarian issues, and the long overdue justice for martial law victims. Regarding military capability, the Philippines was understandably a strong military power due to its security alliance with the United States. Its force projection was significant thanks to the 1947 Military Bases Agreement (MBA). However, after the Senate rejected to extend the MBA, the Philippines lost its formidable security deterrent. This left a gap in the 1951 Philippines-U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT), eventually resulting in China filling the power vacuum in the region with the promulgation of its domestic sea lane law of 1992, and its occupation of the Mischief Reef in the contested Spratly Islands in 1995. Consequently, the Philippines reacted by inviting the Americans back through the 1997 Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA). Moreover, the devastation caused by the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, the enduring counterinsurgency against Muslim separatists and local communists, and widespread corruption, prevented the Philippines from becoming a strong middle power in the region.

In the third decade of the 21st century, the geopolitical conditions faced by the Philippines continue to present opportunities to maximize its status amid the great power rivalries in the Indo-Pacific. As a treaty ally of the United States, the Philippines is a dependent middle power. As a member of the ASEAN, it is a regional middle power, and as a staunch advocate of international law, it is a global citizen middle power. Arguably, the Philippines’ existing elements of power and its navigation in the international system can provide ways forward on how to hedge in the age of uncertainty, particularly in the context of the post-COVID-19 era.

The Geopolitics of the Philippines in the Context of the US-China rivalry

The Philippines is a collection of more than 7,000 islands situated at the intersection of the South China Sea, the Indonesian archipelago, the Philippine Sea, and the Pacific Ocean. It forms the outer edge of maritime Southeast Asia, and for much of its modern history has served as a gateway between the Pacific and the rest of Asia. The proximity of the Philippines to China and Japan also provides the former with access to vital sea routes for trade and commerce. Being at the entrance of maritime Southeast Asia, the Philippines has cemented its geopolitical role not only in the sub-region but also in the greater Indo-Pacific.

The strategic location of the Philippines serves as a tipping point in the great power rivalry between the U.S. and China. Looking at the geography of the Philippines, it has the potential to change the balance of power between the two states. For the U.S., engaging closely with the Philippines will allow it to effectively encircle China’s assertive maritime ambitions in the Indo-Pacific and limit it from expanding its influence outward. However, for China, forging stronger relations with the Philippines at the expense of the U.S. will allow it to break out of its cage. As a result, the geography of the Southeast Asian state can cause major power shifts in the greater Indo-Pacific region.

The Philippines in the U.S. Equation

With the devastating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with the assertive actions of China in Asia, the U.S. seeks to check the latter’s influence and power projection capabilities in the greater Indo-Pacific. However, after entering a period of economic and military decline, the U.S. cannot commit to its global ambitions effectively. As a result, it has forged closer relations with states that have the potential of checking China’s steady rise. Among these states are Japan, South Korea, Australia, and India. What is important to note is that the Philippines too can play a critical role in forwarding U.S. strategic objectives in the Indo-Pacific vis-a-vis China.

Looking at the map of Asia, the Philippines is perfectly positioned to check China’s growing presence in the Indo-Pacific and keep it locked in the South China Sea. Being a treaty ally, it may seem that the U.S. has it all in the bag with its strategic ambitions vis-a-vis China; however, under the Duterte administration, the Philippines has had a wavering relationship with Washington. After a series of negative statements by President Duterte targeted at the U.S., it may seem that the Philippines is slowly gravitating away from its traditional treaty ally; however, the rhetoric does not always match the practice.

Despite the order to terminate the VFA by the Duterte administration in February 2020, the U.S. still remains committed to helping the Philippine military become a modern fighting force. During his visit to Manila in 2019, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo explicitly clarified that any armed attack by China on Philippine military personnel or public vessels in the disputed South China Sea would trigger Article 4 of the MDT. Considering that the Philippines has not yet severed its alliance with its traditional security ally, it would be in the best interest of the U.S. to engage more constructively with the former and boost its military capacity in order to effectively check China on its behalf. The road for Washington, however, would not be easy considering that the Philippines remains wary of U.S. intentions of using it as a pawn in its great power competition against China. This goes against the current Philippine administration’s so-called independent foreign policy.

China’s Growing Relations with the Philippines

In 2016, President Duterte announced the Philippines’ separation from the U.S. in a speech before a Beijing economic forum. The event reflected a new age of closer relations between China and the Philippines. True enough, the Philippines has subsequently made strides to enhance and develop its cooperation with Beijing in a multi-dimensional platform. In fact, President Duterte’s first major foreign policy decision, barely a month into office, was to effectively disregard the Philippines’ historic legal warfare victory against China. Moreover, he nonchalantly announced that he will “set aside” the arbitral tribunal ruling at The Hague which rejected the bulk of Beijing’s expansive claims in the South China Sea.

In 2018, Chinese President Xi Jinping arrived in the Philippines for a two-day state visit. It was the first state visit by a Chinese President to the Philippines in 13 years. The visit served as a milestone for China-Philippines relations. During Xi’s visit, both states decided to raise the bilateral relationship to one of comprehensive strategic cooperation; in addition, they witnessed the signing of 29 cooperation documents. Improved bilateral relations has also elevated China’s status as the Philippines’ largest trading partner, second-largest source of inbound tourism, and biggest growth driver in local property development.

As the Philippines is actively seeking both foreign and domestic capital to upgrade and expand infrastructure, China has simultaneously been making efforts to channel more investment into the country in areas that revolve around infrastructure and manufacturing. These sectors are considered as extremely sensitive considering that China has a record for taking over critical and strategic infrastructure projects when states are unable to pay back their investment loans. In addition, China seems to be getting closer to the Philippines in order to escape from the encirclement of the U.S. Through the Philippines, China would be able to project its influence outward.

China still faces hurdles in realizing its goals. Despite rosy relations, the Philippines remains wary of China’s intentions. In a survey done by the Social Weather Stations (SWS), most Filipinos still do not trust China. The Philippines has also shown its discontent with China’s increasingly assertive maneuvers in benign ways. The state has expressed support and solidarity with Vietnam after the ramming and sinking of a Vietnamese fishing boat by a Chinese coast guard ship in the South China Sea. The Philippine government has also lodged two diplomatic protests in April 2020 against China’s assertive actions. These illustrate how the Philippines is not readily jumping onto the Chinese bandwagon just yet, which poses a strategic challenge to China’s long-term power ambitions.

Future Trajectory in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused states to react with panic and aggression; however, it is important for middle powers like the Philippines to weigh their options and critically assess the situation. As both China and the U.S. continue to grapple for power and influence to constrain one another, the Philippines must use its geography as leverage in this tumultuous power equation. It is crucial for the Philippines to pursue its national interest; as a result, it must carefully tread vis-a-vis its relations with both the U.S. and China. Moreover, it is not necessarily the Duterte administration alone that will keep this balance going; rather, it is the enduring elements of power that the Philippines has that will make a difference.

The pandemic has brought unprecedented damage to the Philippines and the rest of the world. Unwanted shocks may temporarily remain. As a middle power, the Philippines has the potential economic and human resources due to a thriving economy and a rising middle class. Its international prestige continues to endure thanks to its defense networks, economic relationships, and diplomatic influence. Although lacking in resilient institutions, its cultural influence through information flows, people exchanges, and cultural projection continue to increase its relevance thanks to its existing, albeit struggling, democratic system. Although lacking in strong military capability, its modernization efforts remain unhampered and force projection continues to develop despite claims of defeatism. To attain an upward trend as a middle power, the Philippines needs to strengthen its military capability and the resilience of its institutions. This is an opportunity for the Philippines to maximize its geopolitical potential in the context of the current great power rivalry.

Don Mclain Gill is a current graduate student under the Master’s in International Studies Program in the University of the Philippines, Diliman. He has written on regional geopolitics and India-Southeast Asia relations.

Joshua Bernard B. Espeña is a defense analyst in the Office for Strategic Studies and Strategy Management, Armed Forces of the Philippines (OSSSM, AFP). He is a current graduate student under the Master’s in International Studies Program in University of the Philippines, Diliman.