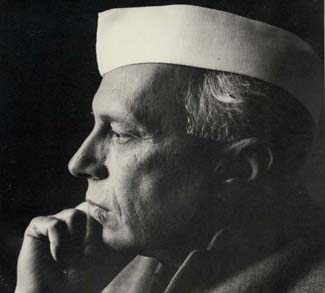

The NDA government has recently expressed its intention of revamping the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML). The move has stirred a commotion in Nehruite and Congress circles, who see something sinister in it, like an ideological assault on Nehruvian philosophy.

To reinforce their adherence to personality cult and swear their Nehruvian loyalty, they do not hesitate to misinterpret, rather distort, the idea of revamping the museum. The truth is far from it. Revamping carries no apprehension for denigrating the stalwart of India’s freedom struggle.

What the government stated was that it desires to expand the content and coverage of the NMML in a way that it assumes the status of a national museum representing the saga of a crucial era of Indian history: the freedom struggle and the building of the Indian Republic.

We think no proposal of changing the name of the museum is on the anvil; there is no need or sense in doing so.

Nehruites need no briefing on the role of a large number of their hero’s close associates and colleagues, who waged the freedom struggle with him, hand-in-hand. These veterans decided to sink or swim together. Nehru always held them in great esteem, a sentiment they reciprocated with equal warmth.

However, post-Nehru generations of Indians, inquisitive about the role of these veterans, their struggle and the aftermath of freedom, quite naturally ask why so many of the celebrities and colleagues of Nehru should not find their proper place in the annals of history, written, oral, or visual. If the Modi government responds to this question, it will only be serving national history and its architects.

Against the wishes of his cabinet colleagues, including the deputy prime minister, Nehru went running to the UN Security Council to bail him out in Kashmir.

There are many stars shining brightly in the firmament of India’s freedom and post-freedom struggle. They all carried the flames of patriotism within their bosom; they were not ordinary leaders whom the nation can afford to deny a place in the roll call of honor. If Dr. Ambedkar gave India a masterpiece of a Constitution that has gone down in the history of humankind as the second Magna Carta, the Sardar welded the parceled and fragmented India into one solid unit which gives new meaning, content, and strength to the Indian nation. If the Modi government honors them by juxtaposing them and their aura to that of the leader with whom they collaborated and steered the ship of the state, it will undoubtedly add something to the status of Nehru rather than take away from it.

Half a century has passed by since when Nehru left us. During this period, India has taken long strides along the path of development and freedom. This is the age of research and revaluation. Facilitated by digital technology, our youngsters have developed sharp and precise sense of inquiry and academic research. They delight in probing our past and envisioning our future. They are assessing our leaders to appreciate their contribution. At the same time, they are on a faultfinding mission not to repeat blunders.

For example, in the case of Nehru, they pause to unravel the Nehru-Gandhi clannish mystique. Dynastic rule for so many decades in a democratic and egalitarian India of post–independence era is a strong irritation to the new generation of Indians. It brings to memory our revulsion of medieval potentates in the East. It has created an impression among many people in and outside the country, that Indian democracy is incapable of wriggling out of personality cult and giving true content to democratic dispensation.

Since everything in India, from farms to factories, roads to airports, crèche to colleges, projects to prisons, dams to tunnels, railway junctions to metro co-terminuses, sports stadiums to space centers – everything bears the impress of the Nehru-Gandhi name-plate, thanks to a host of sycophants and pseudo-nationalists, the youth ask whether India remains mortgaged to Gandhi-Nehru dynasty until eternity. Here personality cult has become all-pervasive.

There could be more disturbing questions. Young researchers want to know whether Nehru‘s personality was really as tall as has been projected by his protégés and beneficiaries, especially the euphoric media. They ask this question after evaluating his contribution and assessing the impact of his shortcomings.

As a public leader, Nehru was not an extraordinary orator. Apart from a mediocre conversationalist in Hindustani, he had no stunning linguistic skills to mesmerize his audience through oratorical flabbergast just because he had no mastery over any of the vernaculars. Yes, he wrote and spoke good English, thanks to his stint at Cambridge. Yet he did not win any formal academic degree on his own merit. In a public address in Srinagar, he had a slip of tongue saying that he could clear studies in natural science by greasing the palm of his examiners.

Nehru cannot seek refuge behind the universal truth that man is fallible. He was the prime minister. The fallout of his fallibility was horrendous on the national plane. In his vainglory, he showed a prime minster who practiced obduracy while publicizing democracy. Eleven out of twelve members of Selection Committee of Congress High Command preparing to select by secret ballot the prospective candidate to be the prime minister of India, voted for the Sardar. Nehru threatened Gandhi with resignation from Congress if he were not the prime minster. Gandhi succumbed and trivialized the spirit of democracy. The Sardar saved the situation by withdrawing in favor of Nehru. Who was a greater patriot?

Against the wishes of his cabinet colleagues, including the deputy prime minister, Nehru went running to the UN Security Council to bail him out in Kashmir. He did not even consult the Parliament. We are reaping the whirlwind from the wind that has blown from governance with arrogance.

The Sardar resolved the issue of 560 small and big princely states of India by incorporating them into the Indian Union. Nehru monopolized the J&K conundrum, boasting only he had the gift of the gab to resolve the festering sore. Sixty-eight years have gone by. We invested men, money and material, and today Pakistani and ISIS flags flutter freely on housetops in Kashmir.

In Jammu, Praja Parishad nationalist resistance movement exposed Sheikh’s masked profile under which he dispensed autocratic, parochial, and communal governance. In a public speech in Jammu, Nehru howled he did not know who this Premnath Dogra was and what he stood for. Four years later, Nehru removed his bosom friend from power, put him behind bars, and initiated a case of sedition against him. A decade later, and just days before his death, Nehru sent the same bosom friend to negotiate a deal on Kashmir with General Ayub Khan of Pakistan, who contemptuously turned down the offer of a Confederation brokered by Nehru-Sheikh combine. Neither the Sheikh nor Nehru, the “democratic duo,” had taken their respective law making bodies into confidence. Can we stop researchers from conducting in-depth inquiry into sordid phenomenon like this?

The so-called Non-Alignment Movement of Nehru that made a mockery of Indian democracy and foreign policy met with an ignoble end even during his own lifetime. When China attacked us in 1962, Nehru begged the U.S. for weapons, ammunition, and war machines. The young researchers ask was Nehru a democrat, a Marxist, a Fabian, a humanist, a nationalist Muslim, or a Trishunka hanging between earth and sky.

Once I asked my late friend and guru Dr. N.N. Raina – the father of leftist movement in Kashmir – why he declined the offer of Nehru to be his private secretary, and instead, proposed the name of Dwarkanath Kachru, the guru said,” He (Nehru) is a half-baked socialist and I am a diehard Marxist-Leninist. How could we two pull together?”

Curiously, in his first and last meeting with Stalin in the Kremlin in 1949, Indian Ambassador Dr. Radhakrishnan was taken aback when Stalin bluntly told him that as long as India had “the running dog of British Imperialism as her prime minister, nothing would change.” Stalin had in his mind the sudden declaration of cease-fire when Indian army was poised for a full-blooded attack on Muzaffarabad in 1948. When Indian forces captured Uri and were preparing retake of Krishanganga Valley, a message from Clement Attlee, the British Labour Prime Minister came to Nehru saying “thus far and no further.” Those who know the map of the region understand the subtleness of Attlee’s comment. Nehru could not wriggle out of the hangover of Lord Curzon’s notorious “Forward Policy in Asia.” The Indus Water Treaty is now coming under severe criticism by serious researchers.

This notwithstanding, Nehru’s scientific and techno-savvy temper, his love for modernity and open society, his inherent desire for world peace and a social order of respectable standard and finally his receptivity to the freedom of press were his marked qualities.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.