On February 19, 2012, in an interview with CNN’s political pundit and Middle East expert Fareed Zakaria, Joint Chiefs of Staff General Martin Demspey stated that the United States is of the opinion that Iran behaves as a rational international actor. Zakaria also described Iran as a rational actor on the world stage in an article in the Washington Post on February 15 in which he argued against an Israeli strike on Iran. Both comments, on the surface at least, are surprising and have brought to light a number of issues underlying the current state of international diplomacy. General Dempsey’s statements were further reinforced by Meir Dagan, the Ex-Chief of the Mossad on CBS’s 60 Minutes.

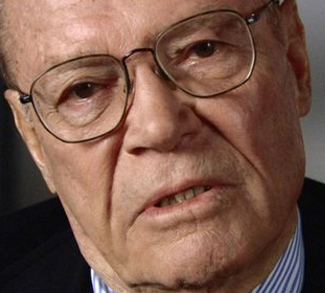

Upon hearing General Dempsey’s comments, I immediately thought of former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s Lesson # 2 in Errol Morris’s seminal documentary The Fog of War (apparently I am not alone – see Iranian rationality: a lesson from Robert McNamara by Tommy Berzi entitled “Rationality will not save us”). To understand the context of McNamara’s lesson it should be noted that McNamara was an early proponent of rational choice theory (i.e. evidence based decision-making) and was one of the first high-ranking American officials to follow this theoretical framework of diplomacy. Most likely, this perspective on international diplomacy stemmed largely from his work as a whiz kid with Ford Corporation in the 1950s, and his short tenure as President of the company in 1960.

When McNamara was appointed as Secretary of Defence under the Kennedy administration, his first major international challenge was the Cuban Missile Crisis. Rational Choice Theory and Rational Actor Theory find their origins in political discourse from the sociological concept of Game Theory popularized by Nobel laureate Thomas Schelling in his most famous work, The Strategy of Conflict. Schelling applied Game Theory to the sphere of political diplomacy. He argued that nations predominantly behave in a way that is in their best interest. At the same time, they do their best to avoid potential military threats at all costs. Michael Kinsley, Schelling’s former student and Op-Ed writer for the Washington Post, illustrates Schelling’s theory with an anecdote about two people chained together at the top of a cliff, each trying to convince the other of his willingness to jump off the edge. Kinsley argued that the individual that can convince the other side that he is willing to take the risk, forces the other side to capitulate, thus winning the game and the prize. The parallels to the current Iranian situation are obvious.

McNamara claimed that during the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis the Kennedy administration received two letters from Khrushchev: a ’soft’ personal letter addressed directly to Kennedy and a hard-line letter addressed to the administration threatening military engagement. Thankfully, US officials, including McNamara, treated the ‘soft’ letter as Russia’s official position.

Like the Russians in 1962, the Iranians are currently sending two distinct messages to the West: 1) Iran is willing to cooperate with the IAEA and engage in productive diplomatic discussions; 2) Iran is hell-bent on the destruction of Israel and is only interested in engaging in protracted diplomatic discussions to delay its inevitable pursuit of enriched uranium. The question the international community faces now is should we listen to the Iran that spouts hatred of Israel and the second coming of the Mahdi, or, do we treat these outbursts as Islamic propaganda and focus on the Iran that works somewhat cooperatively with the IAEA and is a member of the nuclear non-proliferation treaty?

It is here that McNamara’s first lesson, “Empathize with your enemy”, seems profound. Empathy is defined as the “ability to understand and share the feelings of another”. Many experts and political pundits agree that Iran is a rational actor. Therefore, Iran’s mixed messages should be viewed in the context of its internal politics. Rather than viewing Iran as a two headed hydra, political analysts should to attempt to empathize with Ahmadinejad and ask what message he and his troubled political party, Alliance of Builders of Islamic Iran, are trying to send to the people in Iran and its Supreme Leader, Grand Ayatollah Ali Khameni. Clearly, Ahmadinejad wants to project a strong, vibrant and autonomous Iran to both its people and the Supreme Leader in order to shore up parliamentary support rather than sow the seeds of war.

Last week’s parliamentary results signalled a significant shift in Iranian domestic politics as conservative loyalists voted to ally themselves with Khameni. Khameni’s increased consolidation of Iranian power and his recent nod of approval to Obama’s policy of engaging in diplomatic discussions can be seen as a positive omen in this ongoing game of political topsy-turvy.

It is in this context that Khruschev’s letter to Kennedy on that dark day in 1962 seems uncannily relevant for both Western and Iranian diplomats alike:

“…Mr. President, you and I should not now pull on the ends of the rope in which you have tied the knots of war, because the harder you and I pull, the tighter this knot will become.”

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect any official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com.