In late April, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) concluded its 26th summit in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The summit took place amidst China’s land reclamation activities in the South China Sea, which continue to be a potential flashpoint in the region. While the issue has received significant attention from member states, meaningful progress on the dispute is still slow with the bloc shying away from criticizing China directly over its behavior in the area. The final statement with a day-later release however was still stronger than usual, as Malaysia’s Prime Minister Najib Razak stressed upon an urgent need to address ongoing reclamation works in the South China Sea.

The heavier than usual statement, as expected, triggered an angry reaction from Beijing, with Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hong Lei saying that ASEAN should refrain from making statements about the dispute as not all of its members are involved. This is yet another indication of Beijing’s preference for bilateral solutions instead of those negotiated through multilateral framework such as ASEAN. More importantly, Beijing’s exploitation of the bloc’s inability to come together as a united force in the South China Sea dispute could also be regarded as a driving force in its ever-increasing assertiveness in the region.

As host of this year’s summit, Malaysia’s decision to avoid overtly irking China in the South China Sea dispute is a clear reflection of Najib administration’s desire to lead the bloc in a neutral direction while maintaining Kuala Lumpur’s close economic ties with Beijing. While this year’s statement was stronger than previous ones, vocal critics of China such as the Philippines and Vietnam still insisted that it should have gone further, namely by calling for an international tribunal. The Philippine President Benigno Aquino, for instance has called for a stronger regional stand and said the dispute was a “regional issue” with several ramifications, namely freedom of navigation and damage to maritime environments.

Critics have argued that the failure to speak with one voice is ASEAN’s biggest diplomatic challenge since its formation, and it will likely to make the bloc less relevant despite its aspiration to become a viable economic community by 2015.

This was not the first time a host country has sought to tone down criticism of China’s behavior in the South China Sea. Similarly in 2012, Cambodia’s refusal to be drawn into the dispute ultimately led to the breakdown of the summit with members failing to agree on a joint communique mentioning the Scarborough Shoals, a contested area between China and the Philippines. The episode was disastrous as it led to acrimonious exchanges between Phnom Penh and Manila as well as demonstrating that the “ASEAN way” of consensus had failed miserably. The absence of a communique that year also illustrated that not all members have shared strategic concerns when it comes to the South China Sea, further dealing a blow to a coherent response to China’s aggressive stance.

Although Indonesia’s then-foreign minister Marty Natalegawa managed to narrow the differences by way of “shuttle diplomacy,” the underlying problem still lies in Beijing’s ability to establish close economic ties with the individual countries of the bloc. In most cases, these countries’ interdependence on China for trade also bears with it an opportunity cost, such as offering concessions on security-related matters like Beijing’s adherence to the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC). Without balancing economic interests and security ones, China will be able to jostle the bloc around whenever it feels threatened by individual member states in the bloc by offering various incentives to other members, splitting them further apart.

In addition, ASEAN’s decision-making formula of consensus among all member states for a proposal to move forward is detrimental in this case. As demonstrated in the Cambodia incident, a veto by a member will effectively kill any proposal therefore preventing progress on the matter. This is because in contrast with common economic goals as laid down in the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), members do not share a common view when it comes to their “threat perception” of China. For countries like Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia, the South China Sea dispute is ultimately an issue between their neighbors such as Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam, and Beijing, and as such is not worth risking their bilateral ties for. Without clearly defining the strategic interests of ASEAN, this has not only resulted in frustration among member states but also set a dangerous precedent should there be disputes over security-related matters with other big powers in the future.

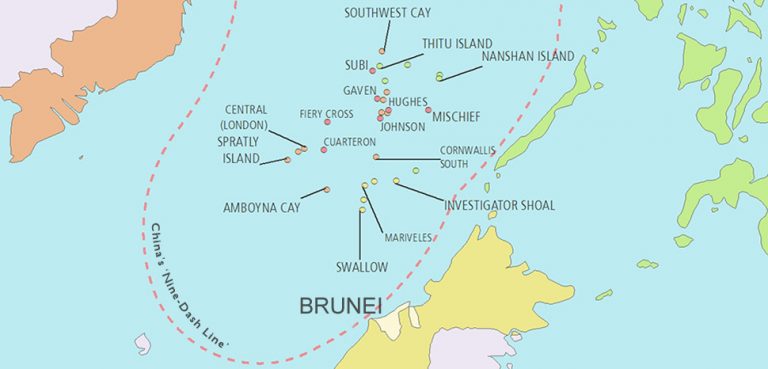

Critics have argued that the failure to speak with one voice is ASEAN’s biggest diplomatic challenge since its formation, and it will likely to make the bloc less relevant despite its aspiration to become a viable economic community by 2015. The absence of a clear response to the dispute is worrying against the backdrop of recent developments such as the 2013 showdown at the Second James Shoal and the placement of an oil rig close to Vietnam by China, both of which have the potential to escalate into armed conflict. Increasingly intimidated, it is therefore not surprising that countries such as the Philippines and Vietnam have instead chosen to deepen their security ties via traditional tools such as strengthening bilateral dialogues and improving diplomatic co-ordination on the South China Sea issue. For Hanoi and Manila, China’s so-called “nine-dashed line” is simply illegitimate and the adoption of common positions among them is vital for the ultimate culmination of the South China Sea dispute as a bloc-wide strategic issue.

The division within ASEAN needs to be resolved so that the talks to establish a Code of Conduct (COC), often rejected by China, can move forward and be implemented. However, against a backdrop of China’s closer economic links with individual member states, such unity will most likely be harder to forge as national interests often supersede regional ones therefore making a paradigm shift more necessary than ever. This means the so-called “gradual progress and consensus through consultations” approach that require all ten-member states to reach an agreement will need to be changed. Instead, the “ASEAN-X” formula that has been used on trade, investment, and economic issues shall now be considered for security-related matters of such magnitude. Under this formula, a reasonable majority of member states will be able to make a decision despite a veto so that it can prevent a single state from hijacking the entire agenda due to a conflict of interest. In the South China Sea dispute, this means member states, particularly claimants such as Brunei, Malaysia, Vietnam, and the Philippines as well as interested stakeholders like Indonesia and Singapore can pursue the establishment of a COC in the area while Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos can opt out by abstaining from the voting process.

The change in voting mechanism however should also come with a pursuit of continuous stability in the region. Malaysia’s chairmanship of ASEAN could be a starting point for a new dynamic in the resolution of the South China Sea dispute. Apart from being a claimant, its close ties with China would also be beneficial in pushing the COC agenda ahead. With a combination of incentives and diplomatic capital, Kuala Lumpur should play smart diplomacy within the bloc and with China in reaching a breakthrough on one of the most dangerous disputes of the present day.

Although the summit in Kuala Lumpur has produced a less than desired result on the South China Sea, the room to maneuver is still available for ASEAN and China to steer themselves away from a collision course and head toward the COC instead. The willingness of both sides to abide by international conventions for now should serve as a foundation in restoring the trust deficit between individual member states and Beijing.

However, the question is how long it will take before such adherence to international convention comes to an abrupt end due to unilateral action by any claimant, or even an outside force that destabilizes the region thus undermining Southeast Asia’s relative stability for decades. There have already been signs of tension last week with the Chinese navy warning the United States to back off from the South China Sea after the latter’s deployment of P-8A Poseidon aircraft for surveillance purpose in the area. If mismanaged, this development, together with the Philippines’ and Vietnam’s alliance with the US, could be a tipping point towards full-blown military conflict between the two major powers in the near future.