Point counterpoint is a new series where two analysts assess a pertinent geopolitical issue from opposing points of view. Neither view represents an official stance of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any other institution the authors are associated with. The article in favor of Turkey leaving NATO can be found here.

The idea that Turkey’s relations with the West are on life support is boilerplate wonkery at this point. Whether it’s the country’s purchase of a Russian-made S-400 missile system and subsequent banishment from the F-35 program; Nazi name-calling and other venomous exchanges with European capitals ahead of the 2017 constitutional referendum; divergent visions on the future of Syria and its US-backed Kurdish populations; or yet unheeded demands for the extradition of Fethullah Gulen – there’s no shortage of issues prying Turkey away from its erstwhile Cold War allies in the Atlantic Alliance.

But what is to be done about it?

Some argue that Turkey should leave NATO, voluntarily or otherwise, because its geopolitical orientation under Erdogan is fundamentally incompatible with the alliance. I would counter that this is short-term thinking that risks throwing out the proverbial baby with the bathwater. When one looks beyond the immediacy of this taxing historical moment, the age old Cold War symbiosis is still evident:

NATO needs Turkey, and Turkey needs NATO.

What is NATO, anyways?

Such a question would never be asked in the earliest days of the alliance, because the answer was abundantly clear: NATO was a collective security organization intended to defend liberal democratic countries from the ideological and military threat represented by the USSR, and, from 1955 onward, the Soviet doppelganger of the Warsaw Pact. The existential nature of the threat, whether real or imagined, was essential to the alliance’s Cold War-era success – it helped to smooth over differences among member states and lubricate the politics of vastly disproportionate contributions from the US military.

The collapse of the USSR changed all that. NATO, which had always defined itself in opposition to the Soviet threat, was suddenly deprived of a raison d’être. In the decade that followed, it tried on new hats: expander, peace-maker, democratizer, and counter-terrorism bloc. But the roles never became entrenched in the hearts and minds of NATO’s core electorates, and the resulting apathy eventually opened the door for politicians like Donald Trump, who gave voice to the hitherto taboo idea that NATO is not so indispensable after all.

But the geopolitical landscape is changing once again and shifting toward something that resembles the liberal-illiberal schism of old. This rebooting of history could be decisive for the Alliance, as NATO can once again live up to its original billing as a defender of democratic values, and in this new project Turkey has an important role to play. The key concept here is defense – NATO can provide collective security against external threats from potential state adversaries like Russia and China, including emerging threats like disinformation, election meddling, and cyber-attacks. It can also promote and encourage democratic governance among NATO member states, even ones flirting with illiberalism like Turkey. But in terms of offense, NATO should not have a role, whatever the emotive pitch at the time, as the Libya adventure and its tragic repercussions have so clearly illustrated.

This idea of Turkey in a reinvigorated NATO, one that’s fit for contemporary purpose, admittedly relies on some wishful thinking. After all, Turkey – already a NATO member – has seen a broad erosion of its democratic standards over the course of President Erdogan’s 16-year rule. And even that ‘city upon a hill’ of the United States has not exactly been putting on a clinic in democratic norms lately. But presumably these are temporary trends that will ultimately pass; in the case of Turkey, the winds of change are already being felt in recent local elections. And if the ultimate foreign policy goal is to promote good governance and peace, isn’t a Turkey that’s within NATO far more likely to undergo a democratic resurgence than one on the outside looking in?

Turkey: geopolitical lynchpin between East and West

Questions of governance aside, Turkey remains an invaluable strategic asset for the NATO alliance.

The country is home to 80 million people and boasts a relatively young median age of 30.9 years (by way of comparison, Germany’s median is around 47 years). Thanks to a decade and a half of breakneck expansion (the economy grew 7% on average from 2010-2017), its GDP now ranks 19th in the world and, recent turmoil notwithstanding, Turkey’s demographic profile offers rare breakout potential in an otherwise stagnant (or worse) continental outlook. The country also boasts the largest land army of any NATO country apart from the United States.

Given its demographic, economic, and military heft, Turkey represents an indispensable middle power in the region.

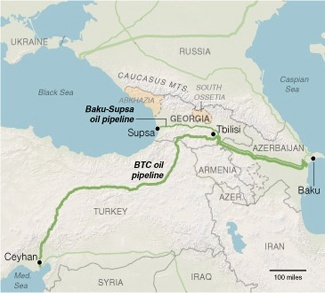

But what region might that be? Given Turkey’s privileged geography at the crossroads of East, West, North, and South, it could refer to most of them: Europe, South and Central Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. It’s hard to imagine a state with more favorable positioning for great power politics. Turkey is a key transit hub for oil and gas, whether it’s the Blue Stream and Turkish Stream from Russia or the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) network linking the Caspian to Western Europe via the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP). It’s also home to the Incirlik Air Base, a crucial hub of US Air Force operations in the Middle East since the earliest days of the Cold War.

Turkey’s post-WWI dimensions belie an outsize voice throughout its neighborhood. As heir to the Ottoman cultural, religious, and historical legacy, Ankara’s sphere of influence projects far beyond its borders, taking Ankara’s diplomacy to places where its Western allies cannot follow. Some of these bonds are cultural, such as the ethnic and linguistic ties between Turkmen populations in the Middle East and Central Asia (for example, allied Turkmen militias in northern Syria that have proven valuable allies in military operations there). Turkmen populations numbering in the tens of millions can be found in Uzbekistan, Iran, Russia, Kazakhstan, China, and Azerbaijan. Others bonds are religious and stem from Turkey’s standing in the Islamic world; the country also has the relatively rare distinction of being an Islamic power that is generally positively disposed toward the West. Under Erdogan’s rule, Turkey has doubled down on its support for the Muslim Brotherhood and was an early and eager backer of the Morsi government in Egypt, and Ankara maintains close relations with Qatar, Iran, and Pakistan.

In the unending Great Game of power politics, Turkey has been and will continue to be a central player. The question is: Does NATO want access to its considerable advantages, or does it want them to one day be arrayed in opposition to the alliance?

In search of a way forward

If the status quo of Turkey and NATO is so favorable in theory, why does every week bring a new blowout between Ankara and its Western allies?

The answer is simple: The world has changed but NATO has not changed with it.

The intrinsic value of NATO to Turkey has always been the protection it afforded vis-à-vis Russia, its imperial competitor and enduring nemesis of the Ottoman Empire. But now the Russia threat has waned, and the old hinterlands of the Black Sea, South Caucasus, and Central Asia are opening up to competition and cooperation from regional powers. Pair this with the rise of a wildly popular nationalist leader in Erdogan, the collapse of Turkey’s EU membership drive, and the passing of the United States’ hegemonic moment and you have all the ingredients for an assertive foreign policy.

It would be a mistake to assume that these systemic trends have made the present acrimony inevitable. Rather, that was accomplished by successive US leaders who have failed to adapt to these new realities. Whether it was the decision to forbid Turkey’s purchase of US-made Patriot missile systems (which led into the eventual S-400 acquisition), or Washington’s persistent military and political support for Syrian Kurds, US officials proven unwilling to listen to, let alone heed, the core interests of a longstanding ally. Exchanges have continued in the Cold War mold: top-down and unyielding, like a parent scolding a child. It’s no wonder that a 2017 Pew poll found that only 23% of the Turkish population had a favorable view of the alliance, a far cry from the median rating of 61%. Even the most ardent supporters of throwing Turkey out of NATO would have to wonder how things have gotten this bad.

It’s no accident that Turkey’s break-up with the West is playing out in parallel with NATO’s own post-Cold War existential crisis. Both are being driven by structural changes in the international system. But fortunately, this also means both problems can be solved at the same time. If NATO can rediscover its credibility as guarantor of the free world and develop a softer touch in addressing the core interests of member states, one that’s more suited to a multipolar and highly complex global landscape, then there’s no reason why Turkey shouldn’t continue to be a valuable member of the alliance long after presidents Erdogan and Trump have faded into the political ether.

Point counterpoint is a new series where two analysts assess a pertinent geopolitical issue from opposing points of view. Neither view represents an official stance of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any other institution the authors are associated with. The article in favor of Turkey leaving NATO can be found here.

This article was originally published on August 13, 2019.