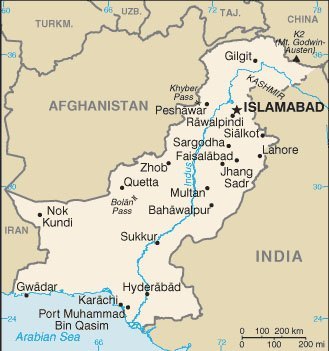

Political stalemate in Pakistan is still strong after crossing the 14-day mark, as an estimated 20,000 anti-government demonstrators are now occupying the theoretically off-limits red zone around the Parliament and the Supreme Court in Islamabad. The heterogenous multitude of protesters is led by ex-cricket player Imran Khan and cleric Tahir-ul-Qadri, who decided early in August to take a stance by organizing a march to ask for Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s resignation, alleging his responsibility in the deaths of 14 people during clashes with the police – the so-called ‘Lahore massacre.’ This incident was the last straw of long-simmering political tensions that began with opposition politicians accusing Sharif of vote rigging in May 2013 elections. The incumbent prime minister and the leaders of the protest have not been able to reach a compromise yet. While the former is firmly refusing to step down as head of the government, the latter are maintaining that they are not going to accept anything less than his full resignation.

Though these political skirmishes are gathering most of the media attention, the economic health of the country is rapidly deteriorating, as confidence in the markets has been seriously undermined by the severity and persistence of this democratic crisis. This is an unfortunate turn of the events, especially after Pakistan experienced moderate positive signs with a 2014 GDP growth of 4.1% and a projected 4.3% figure for 2015. Furthermore, in the middle of July, Moody’s raised the foreign currency government bond rating to ‘stable’ from ‘negative,’ a remarkable achievement that is now likely to be short-lived.

The KSE 100 Index in the Karachi Stock Market (KSM), the nation’s largest stock exchange, lost 4.6% of its value on August 11, plunging to 28,037 points. The drop occurred as opposition leaders called on their supporters to gather up and put ‘the March,’ as it was christened, in motion. In the aftermath, the markets managed to orbit around the 28,000 psychological threshold, but the significant drop of the index in early August was nonetheless followed up by relative instability in the KSM. The oscillations of the exchange were highlighted by a 1.5% drop and rebound on August 28, which coincided with new statements from Imran Khan, who deemed the day to be a likely turning point in the crisis. This climate of uncertainty comes after the record month of July for the financial plexus of Pakistan, which saw the value of its stock market rise to attain a 68-year high just on the eve of this recent downward trend.

Repercussions for the national currency were not late to show up, as the rupee has been steadily losing value against the dollar, touching its 6-month low against at a 103.10 exchange rate on August 25, in what was also the largest single-day drop in the past five years. Finance Minister Ishaq Dar has recently declared that 450bn rupees ($4.37bn) were lost due to capital market volatility since the onset of the protests.

Though these political skirmishes are gathering most of the media attention, the economic health of the country is rapidly deteriorating, as confidence in the markets has been seriously undermined by the severity and persistence of this democratic crisis.

This is unsettling news for a country that benefited from a $6.8bn IMF bailout loan last year. Now due to the waves of political unrest, the IMF has linked the release of the next $550M tranche of the loan to a 4% increase in the power tariffs, effective from September 1. The condition set by the IMF carries important economic and political consequences, considering that Pakistan has been facing a long lasting energy crisis that has held back economic growth, with a daily power shortage estimated between 4,000 and 7,000 megawatts (MW) – an amount exceeding a third of the total national production – which results in daily power cuts lasting several hours. Moreover it does not come as a total surprise that these IMF requests proved to be fertile ground for the already exacerbated political dispute. Indeed, shortly after the measure had been announced, Imran Khan made an appeal to his supporters to stop paying taxes and electricity bills in his campaign against Prime Minister Sharif. The position assumed by Khan collides also with the tax consolidation policy implemented by the government of Islamabad – also at the request of the IMF – which prompted the overall tax-to-GDP ratio to increase, even though the increment was brought down slightly in April 2014.

The evolution of the protest is uncertain, as too is the future of the government. However, if the situation is not resolved soon, the political-economic mixture will have the potential to become explosive – particularly in the event of a rejection from the IMF in releasing the next tranche of the loan. This is quite possible given the difficulty that the government will face in enforcing the tariff increase. Alternatively, the executive branch might deliberately choose to delay the measure in an attempt to disrupt one of the pressure weapons of the opposition and buy time to let the revolt cool down.

Pakistan has gone down a long, hard road since 2008 in its recovery from the world financial crisis. Despite the colossal efforts made to overcome this near economic collapse, many issues remain still unresolved, which in turn continue to hinder national development. In particular, the failure to host free elections in conditions that would prevent, or at least clear suspicion, of fraud has undermined the democratic process, leading to the present economic fallout.